“T” is for Tunneller

by Bill Alexander

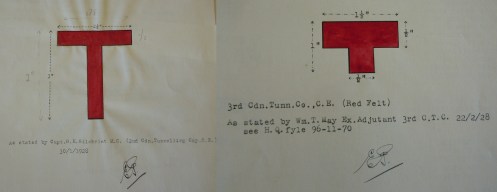

The diagrams for No.2 and No.3 Tunnelling Companies. Source LAC.

During the First World War, many tactical innovations were developed to break the stalemate created by trench warfare. Mining, by tunnelling under the enemy trenches, placing and detonating charges was a technique adopted by both sides in France and Flanders. In the British Expeditionary Force, dedicated tunnelling companies were formed by the Royal Engineers and the engineers from the Dominions and colonies. Tunnelling Companies were responsible for tunnelling, mining, and counter mining activities, including removal of enemy mines and booby traps, as well as other regular engineering jobs as required. Canada, a nation rich in mining operations, was a source of experienced miners and quickly recruited four companies. Organized in 1916, the Canadian Engineer’s companies’ strength was initially 14 officers and 225 other ranks; this would grow to 19 officers and 550 other ranks by 1918. Three companies were sent to the western front under command of the imperial Controller of Mines (Army). The fourth company was converted to a depot and supplied personnel to the other three. The first three companies were deployed to the front, but as BEF assets and not under command of the Canadian Corps.

A Sergeant of No.3 Tunneling Company wearing the insignia of the sleeve.

When the British army and Canadian Corps began adopting battle signs for wear on the uniform, No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3 Tunnelling Companies CE were operating in France and Flanders. These patches of coloured or embroidered cloth were worn on the back or sleeves of the tunic and were introduced to facilitate identification. This practice was extended to the Canadian tunnelling companies who used the simple profile of the letter “T” for the design. Each company designed a unique “T”, differing in construction, colour and size. No 1 Tunnelling Company wore a red rectangular patch with the “T” shape cut out and a piece of black material placed behind. It has also been suggested the “T” shape in black was applied to a red backing. The Acting O.C. No. 1 Coy reported the patch was adopted with the approval of Xth Army Corps on July 2, 1917.[i]

No. 1 Tunnelling Company Sample, courtesy LAC.

No. 2 Coy wore a red “T”, 3 inches high by 2 inches wide. Capt. F.A. Brewster reported the badge had first been worn 7 June 1917 when assisting in the operations of 23rd Division. Authority had been given by the GOC of the 23rd but only for that operation. No. 2 Coy had applied to the Controller of Mines, 4th Army for permanent authority. [ii] No. 3 Coy sent examples of their patches to the Canadian Historical Section in March of 1918. The submission noted the authority was Fourth Army HQ, No/ 21/24 dated 1/3/1918. A diagram of the insignia worn during the war was submitted to the Historical Section in 1928. Image evidence shows the “T” patches in wear on the sleeves of the uniform.

Capt Alex Young, No. 3 Tunnel Company. Courtesy of S. St Amant.

In the early 1918 re-organization of the Canadian Corps, No. 1 and No. 2 Tunnelling Coys were absorbed into the divisional engineering brigades. The insignia for the first two companies was redundant and removed. No. 3 Tunnelling Coy continued as an army troop asset, wearing the tunnellers’ “T” until the end of the war.

Tunnellers T’s showing No. 1 Tunnelling Company with red backing and without, and No. 2 Tunnelling Company, courtesy of the author’s collection.

[i] LAC RG 9 III DI Vol. 4711 Historical Section File 5-D-1-2. No. 1 Tunnelling Coy Regimental Badges.

[ii] LAC RG 9 III DI Vol. 4711, Historical Section File 5-D-2-1. No. 2 Tunnelling Coy Regimental Badges.

Great little article Bill, well done!