by Clive M. Law

The army cadet system has been long-established in Canada and cadet corps were authorized as early as 1861. Many of these units legitimately claim an earlier heritage having been formed as Rifle Associations. The majority of these cadet corps was linked to local schools and military instruction, including drill, marksmanship and First Aid, was provided by local Militia. Oversight of the instruction was often the responsibility of the schools and school teachers. In recognition of this the Department of Militia and Defence (M&D) authorized, in 1908, the Corps of School Cadet Instructors (CSCI)

Shortly after the establishment of the Corps, M&D published a description of the uniform to be worn by its officers. This was published as General Order 62 of 1909. The uniform was to consist of a double-breasted jacket ‘of ordinary civilian length’, fastened in front by two rows of four buttons, of Canadian Militia pattern. The sleeves to be plain with two small buttons placed on the seam. Finally, the jacket was to include cloth shoulder straps of blue cloth with gilt rank badges. The trousers were to be of the same colour and cloth and no stripes were authorized. CSCI officers were to wear the blue Field Service cap, of Infantry pattern. The cost of providing the uniform was to be borne by the officer and was not provided at public expense. Shortly thereafter, in August 1910, the infantry pattern forage cap was permitted as a replacement for the Field Service cap.

The description of the uniform caused considerable confusion in both the CSCI and tailor’s communities as it did not conform in any manner with the Militia uniform of the day. Clarification was requested and M&D replied that the ‘uniform’ was in fact a simple ‘civilian, double-breasted reefer jacket’ which would include two side pockets and a single breast pocket. Buttons were not to be worn on the pockets. The use of shoulder straps with rank badges would certainly have given this civilian attire an unusual appearance. The Quartermaster-General provided this justification for the dress; “This pattern was selected as it is simple and inexpensive, distinctive, and suitable for wear in school or on parade, and is intended for drill order only, as full dress uniform is not required.”

Missing from the uniform was a distinctive cap badge to be worn on the Field Service or forage cap. This was finally addressed in August 1911, when the ‘King’s Badge’ was authorized for wear by Cadets. It appears that the Canadian High Commissioner to London was partly responsible for this. This person was none other than Lord Strathcona, whose interest in, and financial support of, the cadet movement in Canada was considerable. The Strathcona medal continues to be awarded to cadets to this day.

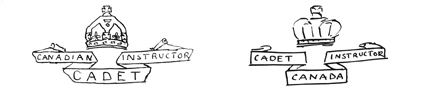

This ‘King’s Badge’ was the Royal Crest, i.e., a Crown surmounted by a lion rampant, below which was a simple scroll with the word ‘Cadets’. The Adjutant-General suggested in a letter that the King had approved the badge for use by cadets throughout the Empire. When shown to the Minister of Militia, Colonel Sam Hughes, he suggested that the badge include maple leaves in the design. These were sketched in, as well as an expanded scroll that now read “Cadets – Canada”, and the badge returned for the Minister’s approval. This unequivocally sets the date for this badge as early 1913 and that its use was for cadets and not instructors. Shortly after approval of the cap badge the Minister approved the use of a “Collar, Maple Leaf” (termed today as a General Service badge) and a ‘Canada’ shoulder title.

A request for pricing was distributed and J.R. Gaunt was selected as the manufacturer. Unlike most badges produced on behalf of M&D, these were to be made available upon repayment (at 5 cents per badge). This approach was taken as it was felt that the ‘boys’ would keep or sell their badges rather than return them into Stores. This would result in additional work for M&D and the argument was made that the cadets would be pleased to pay the nickel. A rush order, for 1,000 badges, was placed so that delivery could be made prior to a cadet visit to England, scheduled for April of that year. Ultimately, a contract for 20,000 badges was issued.

While the design of the cadet badge was under discussion, a suggestion for a variation of the badge, to be worn by CSCI officers was proposed. This badge, in two styles, differed in that the scroll included the word “Instructor”. However, the badge was not approved and CSCI officers were left to wear the approved cadet badge.

While this variant was not accepted by M&D headquarters, the CSCI officers in British Columbia adopted a badge of their own. This badge featured ornate scroll-work of the initials, within a wreath and surmounted by a Crown. This badge was approved in July 1914, (although the outbreak of war may have caused the paperwork to disappear), and continued in wear until the disbandment of the CSCI in 1921 – the result of a re-organization of M&D.

With the authorization, in 1924, of a new cadet organization, the Cadet Services of Canada, the District Cadet Officer for Military District 11 (British Columbia) asked HQ if the CSCI badge could be modified to read ‘CSC’ (Cadet Services of Canada) over ‘NP’ (Non Permanent) and used by the recently approved organization.

Enquiries were made of J.R. Gaunt, which held the dies, and they replied that a change could be made. According to Gaunt, the earlier CSCI badge was “richly gilt, and burnished’. The modified badge was not approved and General Order 57 of 1925 re-affirmed that the authorized cap badge for CSofC officers was the badge authorized for cadets, i.e., the “King’s Cadet” badge with ‘Cadets – Canada’ in the scroll-work. The collar badges remained the Maple Leaf badge. Badges were to be bronze for wear on the khaki uniform and gilt for blue and scarlet uniforms. This GO also authorized the wear of the Infantry pattern uniform for CSofC officers.

In 1943, GO 28 authorized a separate badge for cadets, leaving CSofC officers the sole group to wear the “King’s Cadet” badge. This badge remained unchanged until June, 1953, when the Director of Administration DOA), Department of National Defence (DND) suggested to the Director of Militia and Cadets (DMC) that GO57/1925 was obsolete. DOA proposed that a new badge, featuring the entire title of the Corps (Cadet Services of Canada, and that the Tudor Crown be replaced with the St. Edward’s Crown in accordance with Canadian Army Order 64-5. Further, as collar badges were usually a miniature of the cap badge, that the Maple Leaf collars be replaced. Finally, it was recommended that cap and collar badges be gilt while the shoulder titles be brass.

The approved M&D drawing of the Canadian ‘King’s Cadet” badge. It was Sam Hughes who insisted on the addition of the maple leaves.

It would be March, 1955, before DMC replied, agreeing with the changes to the cap badge but suggesting that the collar badges be modified as; reduced by one-third in size (from 1-1/8-inch high and 1-inch wide, to 3/4-inch high and 13/16-inch wide), and that the shape of the Maple Leaf be changed to comply with the style approved by CAO 64-2. All other recommendations made by DOA were accepted. On 16 April, 1956, the drawings of the badges were approved.

These would remain the authorized badges for the Cadet Services of Canada until the creation of the Cadet Instructor List, later re-organized as the Cadet Instructor Cadre, and the introduction of new badges.

Comparison of the badge initially approved for cadets and CSCI Officers, and the badge authorized for CS of C Officers

Ref – LAC, RG24, Volumes 29712 and 29713

You can ‘rate’ this article by clicking on the stars below.

by Clive M. Law

In early April 1951, the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion of the Royal 22e Regiment wrote to Army Headquarters to point out a discrepancy between the General Orders and the metal regimental title currently on issue. In his letter, Lt-Col L.F. Trudeau wrote that General Order 203 of 1941 states that the title should read ‘R22eR’ and that ‘the Ordnance issue badges for the R22eR do not bear the ‘E’ required by General Orders.’ Lt-Col Trudeau suggested, rather than change the titles, that the GO be amended.

This unexpected missive caught AHQ by surprise and an examination of both the GO and an actual example of the title in question was ordered. However, AHQ did not hold an example and one was requested from the Regiment. On 9 July, AHQ replied that the title was in accordance with Orders and that the measurements of ¼ inch for the ‘E’ and ½ inch for all other letters, and a width of 1 ¾ inches, were all in accordance with the General Order. The letter closed with the comment ‘In view of the above, the comments of the Commanding Officer, 1st Bn Royal 22e Regiment are not understood.’

The title worn by ORs of the Royal 22nd Regiment. The CO of the 1st Battalion believed that the ‘E’ should be represented in a lower case ‘e’.

Shortly thereafter, the General Officer Commanding Quebec District weighed in by pointing out that the original order suggested that the (uppercase) ‘E’ should actually be a (lowercase) ‘e’. However, nothing came from this and both sides agreed to disagree.

It would be another five years before the question of metal shoulder titles for the R22eR was raised and, when it was, it again originated with the Regiment. In September 1956, Maj-Gen J.P.E. Bernatchez, General Officer Commanding (GoC) Quebec Command and a former CO of the Regiment, wrote on behalf of the Regimental Senate[1]

Bernatchez, in his role as GoC, wrote to support the Senate’s recommendation that metal and cloth shoulder titles include the Battalion numeral. HQ did not immediately deny the suggestion but instead asked the Regiment to report on their stock of existing titles, an estimated cost to produce new titles if approved, and the length of time it would take to acquire these. At the same time it was pointed out that this would increase the number of titles from one to six.[2] This seeming willingness was surprising as wartime policy was to avoid using battalion numbers on insignia[3]

Within two months approval was given for numerals to be added to the titles and the CO of the R22eR Regimental Depot was asked to review two proposals and to sign and return the design favoured by the Regiment. These two designs differed in having the numeral precede the Regimental abbreviation, or be placed above it. The chosen design was the latter and the dimensions were described as ‘letters ¼ inch high with the exception of the ‘E’ which is 1/8 inch in height.’ The width was to be one inch.

One of two designs submitted to the R22eR. This one featured the battalion numeral preceding the title.

Examples of the accepted design. None has been found for the 4th or 6th Battalions although they were most likely produced.

In approving the drawing the CO of the Regimental Depot identified that the title was to be made of brass for Other Ranks but ignored specifying the material for titles worn by officers and Warrant Officers First Class and stated in an accompanying letter that the new design would not be worn by officers or WO 1.

In response to a follow-up letter from AHQ, Maj-Gen Bernatchez informed them that the officers of the Regiment had worn a specific metal title since 1920 and ‘it would seem advisable that its use be continued.’ A sample of the title in question was included. Nonetheless, Bernatchez admitted that review of correspondence failed to uncover any information on how the badge came into use but it was requested Orders and Instructions for Dress be amended in order to authorize its continued use. The badge in question featured a crown above the R22eR.

The problematic title. This pattern was taken into wear in 1920-21 but with no authority for its use.

Once seen by AHQ, the R22eR title for officers caused concern. The use of the Crown on any insignia requires the approval of the Monarch and there was no evidence that such permission had ever been sought in the over 35 years that this title was in wear. When asked to explain its history the Regiment was at a loss. No records existed and it was evident that the badge had been brought into use without any approvals – at any level.

A comparison of the sizes of the two titles. As officers wear rank stars it was not possible to make the title much larger.

In an effort to further uncover the history of the title Bernatchez communicated with a number of retired officers as well as with the curator of the regimental museum. None could remember a formal request and all believed that the title dated from the era when the Regiment’s named was changed from 22 Infantry Regiment to Royal 22 Regiment.[4]

Further complicating the issue was a request from the Regiment to retain Tudor Crown (informally termed the King’s Crown) in lieu of adopting the St. Edward’s Crown as was dictated by Army Order 64-5 of 22 April 1953. The Regiment argued that the King’s Crown was taken into wear shortly after they had been awarded the title ‘Royal’ by H.M. King George V, in 1921. They included in their submission that the Regiment was formed under that King’s reign and was the first French-Canadian regiment to be made part of the Permanent Force. Under H.M. King George VI it was the only regiment to stand guard at Buckingham Palace formed completely of soldiers of non-British extraction (in 1938) and saw the Regiment grow from one battalion to three during his reign. Based on these points the Regiment sought permission to retain the Tudor Crown. Existing documents do not include AHQ’s answer to this request but it is known that the Crown did indeed change to the St. Edward’s Crown.

In November 1957, the Royal 22e Regiment made a formal request for retention of the historic metal shoulder title stating;

‘This Regiment is very proud of the fact that it is the first French-speaking Regular unit formed in the British Commonwealth and is most desirous of displaying its loyalty to the Crown by the addition of the Crown in the officer’s metal shoulder badge.’

Accordingly, the Governor General corresponded with Buckingham Palace and, on 17 December 1957, Government House confirmed that Her Majesty The Queen had given her approval. The badge is still worn today by officers and Chief Warrant Officers of the ‘Van Doos’.

[1] A Regimental Senate is usually comprised of the serving Battalion/Regimental commanders as well as previous COs and the Honourary Colonel. They act as a Board of Directors for the Regiment.

[2] At the time the R22eR consisted of five battalions, numbered 1 to 4 and 6 as well as a plain title for members posted to the Regimental Depot and those assigned to extra-regimental duties.

[3] Some exceptions existed, most notably that of the First Canadian Parachute Battalion.

[4] Correspondence from 1926 show that there was a concern about the actual translation of the Regimental name. General Order 149 of 1922 gave the French translation of Royal 22 Regiment as ‘22e Regiment Royal’ which, when translated back into English would read as ‘22nd Royal Regiment’. Records indicate that the translation was supplied by the King’s Printer and they were duly informed. Of interest is that the titles clearly stated R22eR and a note on the file shows that no title was approved for wear by officers. This would indicate that the ‘crowned’ title was in wear as early as 1926.

You can ‘rate’ this article by clicking on the stars below.

by Bill Alexander

At the end of the Second World War, as in previous wars, the victors reaped the spoils of war. But, unlike previous wars the booty was not just gold, silver and fine art. Modern spoils were found in the technical and scientific wealth of the defeated German state. As death throes wracked the Nazi regime in the spring of 1945, the end of hostilities in Europe accelerated the pillage of the industrial German state. The Americans, British and Soviet Union had already begun to identify and locate material for exploitation. Canada as a major participant in the Allied war effort, scrambled to get a piece of the action before it disappeared behind the veils of state and industrial security.

Dr. Paul Larose, National Research Council, at the I.B. Farben plant in Germany, September 1945. DND photo.

In the summer of 1944, Canada had agreed to participate in the Combined Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee (CIOS), an Anglo-American military and civilian group. Organized by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), CIOS was tasked to:

…ferret out German industrial plant and research establishments in the wake of fast-advancing Allied armies after the June 1944 D-Day landings. (Koerner)

As the western Allies closed in on Germany during the last months of the war, the search intensified for advanced enemy science and technology. The CIOS investigations were joined by Consolidated Advance Field Teams (CAFT) and ‘T’ (Target) Forces, special British, Canadian, and American military units that followed behind front-line combat troops and located German industrial operations. These were secured for a later, more detailed examination. Despite a Canadian presence in these initiatives, lukewarm interest limited the extent of participation. [1]

After the German capitulation, the search intensified. The Field Information Agency Technical (FIAT), was established under SHAEF to “co-ordinate, integrate, and direct the activities of the various missions and agencies interested in examining, appraising, and exploiting all information pertaining to the German economy”. This was especially pressing for the Americans who had temporarily occupied key industrial areas in the soon to be Russian zones of occupation. The interests of Canada were obviously not a priority of SHAEF, nor the government of Canada. Canadian participation continued to be of limited scope and without direct instruction or control from the Canadian government. (Koerner) (SHAEF)

The lack of initiative on the part of the Canadian government to develop a policy and implement a program to identify and obtain scientific and industrial technology for Canada left a deepening feeling of anxiety and frustration in some official circles. Vincent Massey, Canadian High Commissioner in the United Kingdom, warned:

Whether we like it or not, a free-for-all is going on; and we must frankly face the alternatives either of joining in the scramble or of being left empty-handed. (Koerner)

The government finally responded in the spring of 1945 by organizing two committees to identify and implement a Canadian program. The first was the Canadian Advisory Targets Committee (CATC), essentially a military organization, formed in March 1945 and focused on military side of scientific and technological information. The second was the Joint Committee on Enemy Science and Technology (JCEST), composed of civilian scientists and military officers. Based in Ottawa it was established in July 1945. The purpose of CJEST was to identify and acquire German technology and scientific data, “including patents, plans, drawings and inventions having possible civilian use.” CATC and JCEST coordinated Canadian activities with CIOS and other related allied organizations. (Secretary of State for External Affairs)

Together, CATC and JCEST:

…identified targets to be examined in Germany and elsewhere in Europe, drew up detailed lists of specific equipment or factories and plants required by the government or private businesses, and oversaw the work of Canada’s teams of scientific and industrial investigators. (Koerner)

Under this mandate, research teams were despatched to Europe. The first contingent of nine scientists embarked before VE Day and focused their investigations on science and technology of potential military use in the war against Japan. In the summer of 1945, Brigadier F.F. Fulton organized the main contingent of the JCEST team of 45 select Scientific Investigators. By late summer, they were overseas, focusing on civilian research.

The Scientific Investigators continued their work into the fall, with their mission accomplishments being highlighted by a press conference held at the Chateau Laurier in December, 1945. The record is unclear after that date, but it appears some Scientific Investigators continued research until the spring of 1946, when the repatriation of the Canadian army removed logistic support. Any remaining ESTI returned to Canada at that time. (Koerner)

ESTI Insignia

Due to the conditions in Germany and the nature of the work, the decision was made to send the team under the control of the army. The investigators were each issued two battledress uniforms and personal kit to facilitate their work. These stores, while military in nature, were to be charged to the Ministry of Munitions and Supply, while the army supplied logistical support for the contingent. To clearly identify the team, unique insignia were designed and issued. A general list metal CANADA cap badge was worn on the standard pattern khaki beret. Each scientist under the authority of the JCEST was issued four CANADA nationality titles plus a pair of SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATOR shoulder epaulet slip-on badges and two arm patches, EST I. (Enemy Science and Technology Investigator). (E.B. Wilson) (Canadian Army Photo 57239/N) (Department of Reconstruction File 7-BF-1 (s)) (Canadian Army Photo 57239/N) (E.B. Wilson)

The CANADA nationality titles were the standard worsted pattern issued to all Canadian army personnel, buff coloured embroidery on khaki worsted wool backing. The SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATOR shoulder badges were made as a slip-on, black printed on a heavy tan coloured cotton drill material. Records indicate 128 pairs were initially obtained from the Travers Apron Ltd of Ottawa, with an additional 100 pairs in a second order in September of 1945. (R.McColm)

The shoulder patch used the abbreviation EST I, for Enemy Science and Technology Investigator. Made using the flocked technique, it consisted of a maple leaf sprayed in yellow on a circular blue felt base. The leaf was enclosed in a near full circle with a tablet at the bottom of the circle bearing yellow lettering E. S. T. I. At least two hundred of these titles were obtained from Unique Products Co. Toronto. (R.McColm) These insignia identified the members of CJEST as they performed their investigations over the summer and fall of 1945.

References

Burgess F.A. Lt.-Col. for Brig. F.F.Fulton, Canadian Advisroy Targets Committee. “CIOS INVESTIGATORS: UNIFORMS and EQUIPMENT.” Letter. March 28, 1945. LAC RG24 Vol 10040.

Canadian Army Photo. “Photo 57239/N.” 1945.

Department of Reconstruction File 7-BF-1 (s). “Backgrounder EST I Press Conference.” LAC RG 25 Volume 5713 File 7-BF-1 (s), 14 December 1945.

E.B. Wilson, Brigadier. “Clothing and Equipment for Cdn Scientists Memo.” Ottawa: LAC RG 24 Vol 10049 File 13 / Cloth /4 /13, 14 August 1945.

Koerner, Steven J. “Technology Transfer from Germany to Canada After 1945.” Comparative Technology Transfer and Society (Volume 2, Number 1, April 2004. ): pp 99-124.

R.McColm, Colonel. “Badges Shoulder Printed Scientific Investigator Badges Emb. Colored EST I Letter.” Ottawa: LAC Badges Cdn Active Service Force RG 24 Series A Vol 2184 File Hq 54-27-60-3 Vol. 7, 25 September 1945.

Secretary of State for External Affairs. “Telegram No 1632.” LAC RG 25 Volume 5713 File 7-BF-1 (5), 16 July 1945.

SHAEF, Advance Headquarters. “Establishment of Field Information Agency Technical (FIAT) of G-2 Supreme Headquarters AEF.” LAC RG 25 Volume 5713 File 7-BF-1 (5), 31 May 1945.

You can ‘rate’ this article by clicking on the stars, below. You can also leave comments at the bottom of this page.

by Roger V. Lucy

Canada raised an Airborne battalion in WWII, which served with the British 6th Airborne Division. For combat these soldiers were issued with the British Helmet, Steel, Airborne Troops, Mk.I (which had a four-point leather harness) and, after 1944, the Helmet, Steel, Airborne Troops Mk.II, with a three point web suspension. For training purposes in the UK, the canvas and sorbo rubber Airborne Troops Training Helmet, Standard Pattern was also issued. Those training in the USA and Canada initially used the US Riddle training helmet or the steel M1 Parachutist Helmet. Later British airborne steel helmets, which were judged to be superior, being less liable to fall off or to foul the parachute shrouds, were procured for training in Canada.

Preparing for their Normandy descent, these soldiers wear Helmets, Steel, Airborne Troops Mk.I heavily covered with netting and scrim.

Immediately after the War Canada’s airborne forces were reduced to a single company, drawn from the Princess Patricia’s-Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI). By the end of the decade, however, Canadian defence policy had changed to meet the possible threat posed to Canada’s vast arctic territory by a potential Soviet aerial descent. To counter this perceived threat, a much expanded airborne capacity was created, the rapid reaction Mobile Strike Force (MSF). The MSF was envisaged as a force able to operate anywhere in Canada, including the Arctic, and required the expansion of Canada’s airborne cadre from company to battalion and then to nominally brigade strength. This put great stress on the supply of a variety of airborne equipment from transport aircraft to helmets. In 1951-2 the MSF required 3,000 paratroop helmets. The receipt of 900 helmets from the UK in 1948, had provided sufficient helmets to equip the newly expanded PPCLI battalion, but not the other battalions, nor the Joint Airborne Training Centre (JATC) at Rivers, Manitoba. When 400 additional helmets were ordered from the British War Office in June 1951, DND was informed that airborne helmet production had ceased at the end of the War and the British had no plans for procuring new helmets for its own use. The Canadian order was too small to justify reopening the line.

To meet this deficiency a number of Canadian Helmet, Crash, Motor Cyclists, Steel were converted to airborne use and issued to the Van Doos and RCR’s airborne battalions. The conversion consisted of inserting a top pad, cutting off the curtain and chin-strap and boring four holes in the rim to take a leather harness based on that of the Mk.I Airborne helmet. The helmets were worn reversed, so the brow pad on the DR helmet became a neck support on the Airborne helmet. Reports from the units indicated that these conversions were considered unsatisfactory.

An example of a Canadian-made steel DR helmet converted to an airborne helmet. It has been painted Paint, Exterior, Flat Green No 3-213. Author’s collection

The interior of a converted DR helmet, the helmet has been reversed, so the brow pad of the DR helmet now supports the back of the soldier’s head. Author’s collection

This photograph shows the RCR Company of the MSF exercising at Malton. They appear to be wearing converted DR helmets. Note the white bands which seem to indicate officers.

This converted DR helmet was later fitted with a new liner and a web Mk.II harness. Peeling away some subsequent coats of paint revealed markings similar to the soldiers exercising at Malton. Author’s collection

In 1952 the British UK resumed airborne helmet production and on 30 January 1953, DND ordered 4,000 new-production Helmets, Steel, Airborne Troops, Mk. II from the manufacturer Briggs Motor Bodies, These were delivered by the end of the year and are readily identified by having BMB MK2 C335-53 (the exact batch number varies somewhat) stamped on the brim and BMB 1953 and the size stamped on the sweat-band.

This 1953-dated British airborne helmet has received a coat of Paint, Exterior, Flat Green No 3-213.and has a Van Doos decal on the left side. Author’s collection

A similarly painted helmet but with airborne Royal Canadian Engineers insignia at the front. W.E. Storey collection

The interior of a the 1953 Helmet, Steel, Airborne Troops Mk.II, still in its original British paint.

In August 1960, the US M1 helmet became the standard helmet for the Regular Army. It was intended to supplant the British Airborne helmet, with the M1 Parachutist Helmet, fitted with the nylon Type II Combat Liner. However, while an example of the parachutists’ version of the US nylon liner was obtained for evaluation in 1962, and the purchase of 6,000 authorized in November 1963, they were slow to enter serial production. In the interim, the British airborne helmets designated “limited standard” and remained in service. There were still 2,131 British Airborne helmets in the Ordnance stocks at Shilo in June 1960, but by late 1963 the larger sizes were no longer available. It is probably at this time that numbers of old airborne Mk.I and converted DR helmets were converted to Mk.II standard, and numbers of the 1953 helmets were refurbished. These helmets have post war Airborne Mk.II harnesses, as well as substitute sweat bands backed by crumbly yellow foam-rubber padding. The size is marked in felt pen.

The interior of the much converted ex-DR helmet, shown above with its replacement liner. Note the very poor quality foam rubber. Author’s collection

The harness of the British airborne helmet was found to be incompatible with the new Canadian NBCW mask It was also unpopular with the troops carrying out training jumps, who complained that its weight tended to cause neck-strain, and that it gave no protection to the lower head and jaw from the parachute shrouds. Some soldiers took to using privately purchased football helmets for training. When, in August, 1964, CJATC sought formal permission for their use, General Allard, forbade their use altogether, noting they were also banned in the USA. In November, 1965, with no deliveries of nylon M-1 parachutists liners in sight, experiments were undertaken to see if a parachutist chin-strap could be fitted to the M-1 steel body. While it was determined that this was feasible, no steps seem to have been taken to issue these helmets in place of British airborne helmets.

Issues of the US-made parachutists helmets (Helmet Steel Parachutist, GS MK I) finally began in the late-1960s and the British airborne helmets were retired. Essentially the M1 parachutist helmet resembled the standard M1 helmet, except the liner was fitted with two web yokes to which were buckled a web chin-strap. On each side of the liner there was a press stud to which was snapped the end of a short extension of the steel pot’s chin-straps. Further tests were carried on M1 parachutists’ helmets at Rivers Manitoba in June1967. These concluded that the nylon Combat Liner Type II was generally satisfactory, except for the way in which its chin-strap was fastened. The brass wire claw buckles on the yokes were difficult to adjust easily and the brass eyelets had a tendency to tear away. Instead the eyelets were omitted and the buckles replaced by two slide buckles. The ends of the modified strap were heat-treated to prevent fraying. So modified, these helmets served on until 1997, when the kevlar CG634 helmet was adopted. This helmet is suitable for use by both airborne and ground troops,

Markings and Insignia

Most British airborne helmets retained either their olive factory paint or were repainted in the universal dark green paint used on Canadian Army vehicles (and everything else of that period) termed: Paint, Exterior, Flat Green No 3-213. Liberal use of nets and scrim remained the norm for field service. At the same time however it became the practice to distinguish the helmets worn by different units, arms and services, either with decals, painted insignia or by painting them in branch colours. Infantry regiments often painted their helmets white; jump instructors red; Signals Corps blue and white; Ordnance Corps Red and Blue etc. Contemporary photographs show these coloured helmets used on exercises, perhaps as a way to identify different units and functions. This practice of applying unit insignia or colours to M1 parachutists’ helmet seems to have been rarely if ever practiced.

This white painted helmet with the PPCLI’s insignia began life as a Helmet Steel Airborne Troops Mk.I, but was later converted to a Mk.II. Author’s collection

This photograph from a pamphlet an early manual on the FNC1 rifle shows a another white airborne helmet, with rank insignia. W.E. Storey Collection

An example of a similar instructor’s helmet, held by the Canadian War Museum. The interior markings indicate it was a wartime issue Mk.II.

An airborne helmet worn by a Lieutenant of the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps. There is a similar helmet in the RCOC Museum. Author’s collection

This black-painted Mk.I Airborne helmet has the red and yellow flash of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps. Jan Nowak collection.

You can ‘rate’ this article by clicking on the stars below. You can also leave a comment at the bottom of the page.

by Clive M. Law

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, and its resulting status of an Axis nation, China approached Canada with the hopes of obtaining critically needed war materiel. This included field guns, trucks and Bren light machine guns. With Canada’s agreement to supply these, a Chinese delegation travelled to Canada. During their visit of the John Inglis plant at Toronto, they asked if Canada could also supply semi-automatic pistols, specifically the Model 1935 Grande Puissance manufactured by Fabrique Nationale, of Herstal, Belgium. Over a period of several months Inglis reverse-engineered the pistol and started manufacture of the pistol. The terms of the agreement included that the each pistol was to include a spare magazine as well as either a cloth holster or a wood combination holster and shoulder stock. Inglis sub-contracted the manufacture of the holsters to Zephyr Loom & Textile (ZL&T), an established, Toronto-based, manufacturer of Pattern 1937 Web Equipment for the Canadian Army.

An example of an Inglis-made Browning Hi-Power, 9mm pistol as produced for the Canadian Army, ca. 1944. Author’s collection

After a first shipment of 4,000 pistols was made the contract was cancelled by the Canadian government due to the inability to deliver the pistols to the Chinese Army. The remaining stock was then accepted by both the Canadian and British Armies – this included the holsters. The holster, made of webbing material featured a single fold-over flap opened with a quick-release tab. This holster was officially termed “Holster, C, No. 2, Mk 1”. Almost immediately complaints were raised about the extremely tight fit of the pistol in the supplied holster. Inglis denied any responsibility, stating that the holster was constructed to Chinese specifications.

Standard issue first pattern (often termed ‘Chainese pattern’ in recognition of the original contract). Anthony Sewards collection

Faced with the situation the Canadian Department of Munitions and Supply set about redesigning the holster to better suit the Canadian Army’s needs. The result was a double fold-over design that offered ample protection to the pistol and provided for quick and easy withdrawal of the pistol. Both models made provision for a spare magazine. The quick-release tab was also improved. As with the early model, this model was also manufactured by ZL&T. This model was officially known as the “Holster, C, No. 2, Mk 2”.

In addition to the obvious physical differences it is worth noting that the early models are all dated 1944 while the second model is dated 1945. In addition, some models will be found in the natural tan colour of unfinished web material while others may be found in a green finish, the result of dying the cotton prior to looming.

Second pattern holster, manufactured by Textile Industries Ltd., and dated 1953. TIL was a re-incarnation of the Second World War Zephyr Loom & Textile (ZL&T) the original producer of these holsters. Author’s collection

Second pattern holster with a black finish as used by Armoured and Rifle units postwar. This model also exhibits the ‘TPL’ stamp, denoting a tropical anti-fungal treatment. Author’s collection

However, there exist two rare models that bridged these two production models. One was a minor improvement by Canada which saw the early type quick-release tab replaced with the improved type – but still utilizing the early holster body. In addition to the quick release tab this holster can be identified by the use of a single rivet attaching the spare magazine sleeve to the holster body (in lieu of the two rivets used on the first pattern) and the 1945 date stamped on the inside of the flap.

Canadian modification to the first pattern holster. All such examples are dated 1945 and feature a modified quick-release tab. Author’s collection

Two variants of the first pattern holster, left, the tan-coloured original featuring the original quick-release tab. Right, a green example showing the second pattern of release tab. Ed Storey collection

Little is known of the other experimental model, developed by the British, and it is possible that only a single example was produced. This style retains the general shape of the first pattern holster but features a deep cutout to allow the user to gain a better grip on the pistol and thereby facilitate its removal from the holster. The single known model was manufactured by the Mills Equipment Company, of London, England, and is dated 1944. No surviving examples are known and only a single photograph, located in DND files, testifies to its existence.

This photograph shows the only known (and possibly sole) example of the British proposed modification which featured a relief cut in the web material. MilArt photo archives

The second pattern holster remained in use through the Korean War until its ultimate replacement by a holster designed for use on the Canadian Pattern 1951 Web Equipment. Nonetheless, as the new webbing was not a universal issue for many years the second pattern holster can be found with manufacture dates into the 1950s. Examples can be found Blanco’ed white, for use by Canadian Provost Corps, as well as painted black for wear by members of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps. The same style can also be found in black leather (with a number of variations of hangers) as well as in a white ‘parade’ version, made of lightweight plastic.

Left, An Officer of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles wearing a blackened second pattern holster in keeping with Rifles’ tradition, ca. 1945.

Right, an immaculately turned out ‘Provost’ directing traffic in South Korea, 1952.

In addition to variations in colour and manufacturer’s marks, some holsters (almost exclusively second pattern) can also be found with a ‘TPL’ marking under the flap, indicating that it has been treated with an anti-fungal process for Tropical use.

Additional information on the Canadian pistol and its many holster variations can be found in the author’s book “Inglis Diamond” available from Collector Grade Publications at http://www.collectorgrade.com/bookshelf1.html

Did you enjoy this article. You can ‘rate’ it by clicking on the stars below. You can also leave comments – see bottom of this page.

by Bill Alexander

Early in the Second World War, the importance of airpower was quickly and forcefully demonstrated. The German blitzkrieg and the lightning fast expansion of the Imperial Japanese Empire were based upon new applications of the role of aircraft in warfare. But, airpower, however impressive in tactical and strategic deployments, had a significant vulnerability. As the Germans had forcefully shown on Crete and in other campaigns, and the Japanese in the Far East, aircraft required landing strips. Defending aircraft and their air fields became a significant component of military planning and deployments.

Canada, with her vast size and immense distances, had early on embraced aircraft as a means of communication and transportation. With the need for home defence, and the implementation of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan early in the Second World War, airpower became a central component in the Canadian war effort. It also became apparent, that though the majority of fighting was overseas, Canada was vulnerable. U-boats were active along the Atlantic coast and in the Gulf of St Lawrence. Threats, real or perceived, of German intrusions on Canadian territory troubled NDHQ. With Pearl Harbour, and Japanese aggression in the Pacific, threats to Canadian security were imminent on two coasts. The possibility of saboteurs, armed landing parties, armed incursions, or even a full scale invasion made attacks on Canadian airfields a real possibility. Denying airfields to the enemy and protecting them from incursions and sabotage became a military necessity. Canada’s home defence divisions were tasked with protecting these essential military assets. (C.P.Stacey 177)

Airfield defence required that several potential threats be addressed. Anti-aircraft defence and flight line security were the respective responsibility of the RCA and RCAF. For defence from enemy ground attack or incursions, active and reserve units of the Canadian army, including some Veterans’ Guard Companies were initially detailed to protect the perimeter of the airfields. (Tonner and Stacey)

Even with these steps, there was an appreciation that the airfields were still vulnerable to incursions or assaults by organized ground or airborne forces:

The rapid development of technique shown by the enemy in the seizure of airfields in the European and Asiatic theatres of war stressed the need for providing as a counter-measure a more specialized type of defence unit than the regular infantry battalion. In CANADA this requirement was first met by the mobilization, in May 1942, of twelve Aerodrome Defence Platoons, five of which were slated for employment in Pacific Command. Each platoon was raised on an establishment of 1 officer and 43 other ranks, and comprised a headquarters, two sections each mounting three 2-pdr A/Tk guns on carriers, and a section of two carriers with 3inch mortars. Two Ronson flame-throwers were added to establishment on reorganization of the platoons (into) Aerodrome Defence Companies in October.

The addition of the new platoons to existing forces at RCAF aerodromes or advanced air bases provided for a mobile defence force at each station, consisting of the aerodrome defence platoon, carrier platoons and lorry-borne infantry, whose special role was that of breaking up and destroying any enemy attack before it reached the inner perimeter, manned by RCAF personnel. (Report No.3 Para 76)

Defence of Canadian airfields became a specialized tasking, with dedicated units of the Active Army in Canada trained to respond to threats to the airfields. The organization of the airfield defence units evolved over the period of their existence. The Aerodrome Defence Platoons were the first manifestation of the force, but due to the inordinate amount of administrative work placed upon the platoon officer, the establishment was changed to company strength in November of 1942.

General Order No. 495/1942, Dated: 31st December, 1942, Effective Date: 23rd November, 1942.

G.O. 495/42 – CONVERSION AND REDESIGNATION – ACTIVE UNITS –

1. The Conversion and Redesignation of the under mentioned Active Units of The Canadian Army is hereby authorized:

Present Conversion and

Serial Designation Serial Redesignation Authorized

1301 1st Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1301 1st Aerodrome Defence Company

1302 2nd Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1302 2nd Aerodrome Defence Company

1303 3rd Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1302 3rd Aerodrome Defence Company

1304 4th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1304 4th Aerodrome Defence Company

1305 5th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1305 5th Aerodrome Defence Company

1306 6th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1306 6th Aerodrome Defence Company

1307 7th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1307 7th Aerodrome Defence Company

1308 8th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1308 8th Aerodrome Defence Company

1309 9th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1309 9th Aerodrome Defence Company

1310 10th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1310 10th Aerodrome Defence Company

1311 11th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1311 11th Aerodrome Defence Company

1312 12th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1312 12th Aerodrome Defence Company

1313 13th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1313 13th Aerodrome Defence Company

1314 14th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1314 14th Aerodrome Defence Company

1315 15th Aerodrome Defence Platoon 1315 15th Aerodrome Defence Company

Even with this reorganization, the management and control of the air defence companies continued to be an administrative headache, and the companies were allocated to two Air Defence Battalions, effective 19th July, 1943. These new air field defence battalions were formed by converting two existing Canadian regiments, the 1st Battalion, Le Regiment de Chateauguay, to the 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (Mit.), C.I.C. and the 3rd Battalion, The Regina Rifle Regiment, C.I.C. to the 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion(The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C. All existing Aerodrome Defence Companies were put under their command, with the 1st Airfield Defence Battalion under Atlantic Command, and the 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion under Pacific Command.

General Order No. 439/1943, Dated: 1st November, 1943, Effective Date: 19th July, 1943.

G.O. 439/43 – SERIAL NUMBERS – ALLOTMENT OF – The following Serial Numbers are hereby alloted to the various Sub-Units of Serial 1071 – 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C. and Serial 1073 – 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C., as indicated hereunder:

Serial Unit

1071A Battalion Headquarters, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.), C.I.C.

1071B No. 1 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1071C No. 2 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1071D No. 3 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1071E No. 4 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1071F No. 5 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1071G No. 6 Company, 1st Airfield Defence Battalion (Le Regiment de Chateauguay (M.G.)), C.I.C.

1073A Battalion Headquarters, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073B No. 1 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073C No. 2 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073D No. 3 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073E No. 4 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073F No. 5 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073G No. 6 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073H No. 7 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073J No. 8 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

1073K No. 9 Company, 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion (The Regina Rifle Regiment), C.I.C.

This reorganization was short lived. The need for air field defence quickly diminished, and many companies were disbanded. The 1st Airfield Defence Battalion was re-converted and re-designated the Regiment de Chateauguay effective September 1, 1944, and then disbanded effective January 18, 1945. ( Le Regt de Chateauguay had been sent to the UK and was disbanded upon arrival there.) The 2nd Airfield Defence Battalion had been disbanded effective November 15, 1943.

Aerodrome Defence Company Insignia.

No distinctive metal cap or collar badges were approved for the Air Field Defence Battalions or their predecessors. Initially, the intention was that the Aerodrome Defence Companies were to wear the Infantry Corps badges. These were not available until 1943, but there is no evidence that they were worn by the Aerodrome units.

In 1942, the Canadian Army had approved the wearing of coloured embroidered shoulder titles for units on active service in Canada. A unique shoulder title was made for the Aerodrome Defence Companies. The title reads AERODROME DEFENCE COMPANY on one arched up line, in red embroidered thread on “French blue grey” melton material. At least 5,000 Aerodrome titles were ordered in June, 1943. Additionally, there exist numerals, worn sub-nominally to identify the various companies. An example of the “4th”, denoting the 4th Company is illustrated below. There have been suggestions that sub-nominals were produced for all companies, but this has not been substantiated. To date, no authorization for the sub-nominal numerals has been located, and no comprehensive list has been compiled, but examples of the following are confirmed in collections: 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15. It is likely that examples were made for 1, 2, 3, and 5. (G.W.Cavey , Memo July 1, 1943.)

The Air Field Defence Battalions adopted the coloured embroidered titles of the parent regiments when they were reorganized in late 1943.

The Regina Rifle Regiment Second World War era shoulder title. The same pattern was worn by the 1st and 3rd Battalions.

Bibliography

C.P.Stacey. Six Years of War. Ottawa: Minister of National Defence, 1955.

Directorate of History. AHQ REPORT NO. 3, THE EMPLOYMENT OF INFANTRY IN THE PACIFIC COAST DEFENCES, Aug 39 – Dec 43. Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 1986.

G.W.Cavey, Colonel, D.O.S. (G.S.). “Memo Badges Embroidrered Coloured, to Dept of Munitions & Supply.” LAC RG 24, Volume 2186, File HQ S4-27-60-13 Volume 3., 1 July 1943.

Tonner, Mark. On Active Service. Ottawa, Ontario: Service Publications, 2006.

by Clive M. Law

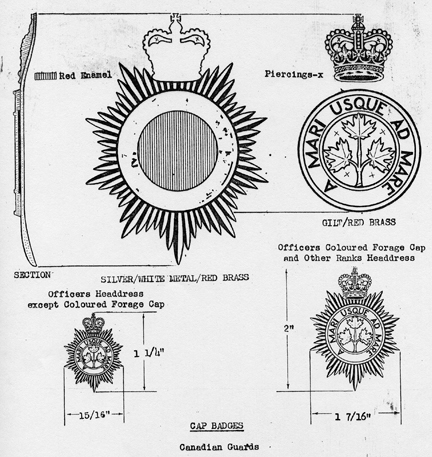

The Governor General’s Foot Guards were established by General Order 16 of 7 June, 1872. The GO was very specific in that “The Corps to be special and under the direct command of the Adjutant-General”. This unusual chain of command immediately set the GGFG aside from other Militia regiments of the day and set the tone that the GGFG were the nation’s regiment and not a City or Rural regiment. In fact, one of the prime reasons for the establishment of a Guards Regiment at Ottawa was to provide the Governor General, and to an extent Parliament, with the ceremony due his office.

Officers, Warrant Officers and Sergeants of the Governor General’s Foot Guards, ca. 1873. Lt-Col Ross is shown seated, centre.

As a Regiment of Foot Guards the GGFG adopted the uniform of their Allied Regiment, the Coldstream Guards. As such they adopted the red plume for the bearskin cap and wore their buttons in pairs.[i] For the better part of the next century, the GGFG looked to Britain for guidance in all matters pertaining to Dress and their headdress and cap badges readily testify to this.

Officers of the Regiment, ca 1885. Note the three officers in cocked hats. These are the Medical Officer, Quartermaster and Paymaster who, as non-combatant officers, did not wear the bearskin cap.

In addition to the bearskin cap, the GGFG wore the variety of headdress authorized by Dress Regulations of the time. In the late 1800s these included the Field Service Cap (Torin pattern), the Forage cap and, for ‘non-combatant’ officers, a cocked hat in lieu of a bearskin.[ii] The use of the Torin cap was interesting as the authorized Field Service Cap for Infantry (from 1898) was the blue ‘Austrian pattern’ cap – similar to the FSC re-introduced in 1937 for wear with Battledress. Another cap was a fur ‘wedge’ style cap worn in Winter. This cap featured an unusual badge (for the GGFG) in that it is based on a Fusiliers grenade.

The early forage caps differed considerably by rank with officers wearing a dark blue cap with a black mohair band, an embroidered badge and a peak with 1/4-inch gold embroidery on the edge. Warrant Officers and Sergeants wore a similar cap but with a metal badge and a white band (Sergeants) or gold lace band (Warrant Officers), while Other Ranks wore a ‘pillbox’ cap with metal badge and white band.

The Commanding Officer, Adjutant and an orderly, ca.1892. Note the Torin cap worn by the Colonel and the two styles of forage cap, bot OR and Officer, worn here. Of interest is the tunic worn by the orderly. Due to limited funds, Militia & Defence could not afford to purchase Guards pattern tunics and provided a quantity of Infantry patern tunics. Some of these were later adapted to double-buttons although the (incorrect) cuffs remained unaltered. MilArt photo archives.

The badge design remained identical for all ranks – a six-pointed star, representing the six extant provinces of Canada in 1872 – although construction differed. The first description of the badges is to be found in the 1898 Queen’s Regulations and Orders which describe the officers’ badge as “A six-pointed star embroidered in silver 1 5/16 inch long by 1 3/8 inch wide. Oval medallion cross in centre of star, with a blue (St. George) cross in the oval”. A smaller, similar but metal badge is authorized for wear on the Torin cap. Other Ranks, who wore the plain Field Service Cap in lieu of the Torin, wore a larger badge as shown below. Perhaps the most interesting point to this badge is the misspelling of the word ‘Governor’.

Often referred to as a Glengarry badge, this pattern was worn by Other ranks on the blue ‘Austrian ppattern’ Field Service Cap. Note the spelling error in ‘Governor’. Author’s collection

Early pattern forage cap. Unlike other infantry regiments were Field Officers display gold piping along the crown, all Guards officers wore this.

The Officers’ forage cap evolved with the introduction of the Staff Pattern of forage cap and the crown became larger. Unlike other Regiments and Corps the GGFG retained a simple band of gold embroidery around the peak for all commissioned ranks, eschewing the Maple Leaf embroidery adopted by Field Officers elsewhere.

In the early 1930s, Headquarters undertook to update the Dress Regulations. The Officers’ cap badge worn at the time was described as ‘In silver, a six-pointed star 1 3/4 inch by 1 3/8 inch; oval medallion in the centre of star, with a blue cross in the oval; cross 10/16 inch by 10/16 inch; and the words “GOVR. GENL, FOOT GUARDS’ placed around the medallion on a blue background.’

While the Adjutant of the GGFG confirmed details with the Coldstream Guards it was discovered that the Officers’ cap badge was not in keeping with British Guards practice. Whereas the GGFG displayed the regimental name, in abbreviated form, in a circle around the St. George cross, every regiment of the British Brigade of Guards displayed the regimental motto. Once this was discovered the Commanding Officer of the GGFG wrote to HQ requesting permission to amend Regulations by removing the regimental name and replacing it with ‘Civitas et Princeps Cura Nostra’ – described in 1932 as representing ‘The state and the head of the State are our charge’.

Two patterns of the Officers’ badge. On the right a variant of the badge with Regimental title and on the left a pierced example exhibiting the Regimental motto. Author’s collection

To support this request the Commanding Officer stated that no immediate expense in the provision of dies would be required as the error could only be seen at close distance and that the change could be made when new badges were ordered. In October 1931, the Quartermaster –General agreed to the change and confirmed a few salient points;

– That the blue cross was of enamel and that this was permissible for officers only, and

– The pre-war badge for Warrant Officer and Sergeants featured a pierced cross.

The brass badge appears to have been used prior to the First World Ward and into the 1920s when it was suplanted by the white metal badge. Pre-war only Sergents and Warrant Officers had a pierced cross although postwar all ranks wore the same badge.

The Commanding Officer also suggested that, when new badges were made, that ‘a more effective badge could be obtained by the rays of the star between the points tapering very slightly inwards towards the centre of the badge.’ This design change was finally adopted, but not until well after the Second World War.

Two GGFG officers. As Officers did not wear collar badges in Service Dress, and the GGFG had no authorized beret badge at this time, the officer on the left has taken a Senior NCO’s collar badge into use.

In addition to cap badges the GGFG have a rich history of shoulder and collar badges as well as rank insignia. The author hopes to present a future article on these.

[i] The number of buttons, within a group, identifies the seniority of (British) Brigade of Guards regiments with the Grenadier Guards wearing ‘single’ buttons, the Coldstream Guards’ buttons worn in pairs, the Scots Guards in groups of three, the Irish Guards in groups of four and the Welsh Guards in groups of five. The GGFG wear theirs in pairs In accordance with their alliance with the Coldstream Guards even though the GGFG are the senior regiment of Foot Guards in Canada.

[ii] These officers were the Medical Officer, Quartermaster and Paymaster. The colour and shape of plume worn on the cocked hat differed for each of these officers.

You can ‘rate’ this article by clicking on thestars (below). You van also leave comments by using the form at the bottom of this page.

by Mark W. Tonner

Two rudimentary devices were used by the Calgary Regiment at Dieppe, which after the raid, would lead to the development of more advanced models of these devices, mounted on the Churchill tank chassis. The two rudimentary devices used by the Calgary Regiment at Dieppe, was the “Oke” flamethrower, mounted in three of the regiments Churchill tanks, and a carpet laying apparatus for forming a trackway that was carried on two bobbins attached to the front of five of the regiment’s Churchill tanks, and was referred to as a “Beach Track Laying Device.”

Background on the Calgary Regiment’s involvement at Dieppe:

Operation Jubilee was the ill‑fated 19 August 1942 combined operations raid carried out against the port of Dieppe. The Calgary Regiment was to land on the main beach at Dieppe, in support of the infantrymen of the 2nd Canadian Division. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the details of Operation Jubilee, but the performance and activities of the Churchill tanks of the Calgary Regiment, that were equipped with the “Oke” flamethrower, or the “Beach Track Laying Device,” on 19 August 1942 are relevant. These extracts from the Calgary Regiment’s war diary, Appendix No. 7, dated 20 August 1942, explain the role envisioned for the Calgary Regiment at Dieppe, and briefly, how the regiment faired, from landing to withdrawal. Since few members of the regiment returned from the beaches, it was largely based on plans, radio logs, and observations from those who did not get ashore:

“The general tank plan was that all tanks would land on the main beach at Dieppe in successive waves. “C” Squadron would assist the Essex Scottish in establishing the bridgehead and taking care of the armed trawlers in the harbour. They would then cross to the high ground on the east side of the River D’Arques to dominate the approaches to the east. “B” Squadron was to assist the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry in establishing the right flank of the bridgehead. They would then push inland and take the aerodrome (airfield) at St. Aubin with The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada. “A” Squadron was in reserve and would land later. Once the beachhead was secure, the headquarters of the German 302 Infantry Division at Arques la Battaille would be captured by the Camerons, aided by either “A” or “B” Squadron depending on the tactical situation.

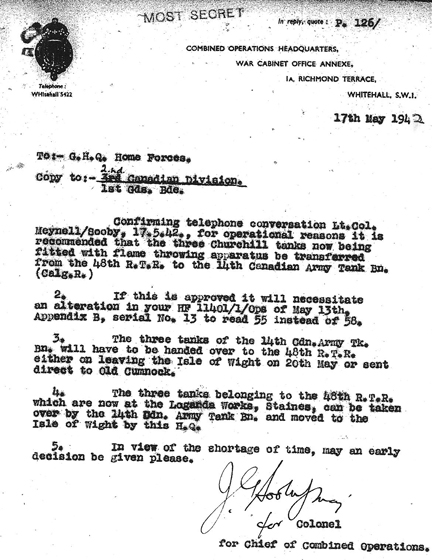

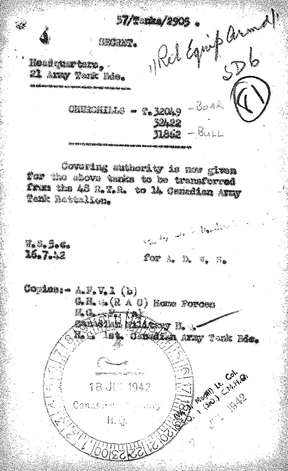

The British Combined Operations Headquarters letter dated 17 May 1942, from the Combined Operations Headquarters to General Headquarters Home Forces, in which it was recommended for operational purposes that the three Churchill tanks fitted with the Oke flame throwing apparatus be transferred from the 48th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, to the Calgary Regiment. Source: Authors’ collection.

On the main beach at Dieppe, the main sequence of events was as follows. Despite the heavy bombardment from the sea by naval forces and from the air by bombers, the enemy’s concealed positions in front of the town itself were not destroyed. They were still able to bring intense fire to bear on any point on the main beach from the moment it was assaulted. The first wave of the Calgary’s tanks got ashore successfully, and some of them assaulted the town. Others, however, were not successful in negotiating the sea wall and did not get off the beach. A number of them soon were immobilized. Nevertheless their crews continued to fight their guns, engaging enemy positions with good effect.

The convening authority for the transfer of T31862, T32049, and T32422, from the 48th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, to the Calgary Regiment (who at this time bore the designation of the 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Calgary Regiment (Tank))). Source: Authors’ collection.

Roads leading into the town were solidly blocked and, in order that the tanks might successfully penetrate into the town, it was essential that these be cleared. The engineers were carrying large quantities of selected explosives for this purpose. Unfortunately, however, the heavy fire that the enemy was still able to bring to bear on the beach caused heavy casualties amongst the sappers (engineers). Despite great courage and determination, they were unable to clear the road blocks. This made it extremely difficult for the tanks to get into the town at all. Consequently the majority of the tanks fought the whole of the engagement from the beach and promenade.

Captain B.G. Purdy, who was commanding No. 8 Troop of “B” Squadron that was specially equipped with flamethrowers, attempted to land as planned on the right of the main beach. However for some unknown reason, his tank went off in very deep water and had to be abandoned immediately. All the tanks that got ashore fought very hard, until they were either put out of action or ran out of ammunition. At about 1225 hours (12:25 P.M.), Major Glenn ordered all personnel to the beach. They were to be ready to abandon the tanks when the boats came in. The fire on the beach at this time had grown very fierce, and casualties in the withdrawing troops were heavy. Only two members of the tank crews who landed managed to get away, and the remainder were either killed or taken prisoner. No. 11, 12, and 14 Troops of “C” Squadron, and the whole of “A” Squadron remained afloat during the operation, lying offshore awaiting orders to go in. About 1300 hours (1:00 P.M.), the order was given to sail back to England.”

The“Oke” flamethrower device:

By the beginning of 1942, under the auspices of the Petroleum Warfare Department and the Ministry of Supply, the British had begun to carry out research and development of tank‑based flamethrowers as a potential offensive weapon. Various prototypes based on the Infantry Tank Mk III, Valentine, were developed and tested, using a two‑wheeled trailer that carried the fuel for the flamethrower apparatus mounted on the tank. After the tests, Major J.M. Oke of the British Army suggested that the jettison fuel container that most tanks were equipped with at the time be used in place of the trailer. The Lagonda Car Company of Feltham, Slough, took up this idea, connecting the jettison fuel container to a Ronson‑type flame projector. They fitted the complete system into a Churchill Mk II tank, which eventually came to be known as the Churchill “Oke.” Having observed trials of Lagonda’s prototype, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Chief of Combined Operations, pressed for the full development of Lagonda’s concept for operational service.

In the centre of this photo from Dieppe, is T68875 Beetle, a Churchill Mk II (Special) of No. 8 Troop, “B” Squadron, The Calgary Regiment, which was fitted with the Oke flame-throwing system. As can be seen, the flame projector was mounted in the front of the tank on the left of the hull gunner’s position and protruded out between the hull machine gun and the left front horn of the tank, the muzzle of which can be seen sticking up above the left track. The tank to the right rear of Beetle, on the shoreline, is T68881 Ringer, a Churchill Mk II, of Regimental Headquarters, The Calgary Regiment. Source: Authors’ collection.

The Churchill “Oke” was basically a Churchill Mk II tank, with a complete Ronson type flamethrower system installed, which consisted of having the rear mounted jettison fuel container connected up to a feed pipe which passed through the left pannier and was itself connected to a flame projector in the front of the tank. The flame projector was mounted in the front of the tank on the left of the hull gunner’s position and protruded out between the left of the hull machine gun and the left front horn of the tank. The flame projector was operated from the hull machine gunner’s seat, and because it was mounted in a fixed position and elevation, the tank had to turn to engage any intended flame target. The basic operation of the flamethrower was that compressed carbon dioxide gas propelled the flame fuel from the jettison fuel container to the flame projector. There, a trigger mechanism opened the pintle valve in the flame projector’s nozzle and projected a jet or pencil of fuel. The carburetor bled petrol into the stream, which was then lit by the action of a spark plug. The range of the Oke flamethrower was 40 to 50 yards.

In May 1942, No. 10 Troop, “B” Squadron, 48th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, was sent to the Lagonda Works at Staines. There, their three Churchill Mk II tanks (T31862, T32049, and T32422) were fitted with the Oke flame‑throwing system. In a British Combined Operations Headquarters letter dated 17 May 1942, from the Combined Operations Headquarters to General Headquarters Home Forces, it was recommended for operational purposes that the three Churchill tanks fitted with the Oke flame‑throwing apparatus be transferred from the 48th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, to The Calgary Regiment. This recommendation was subsequently approved on 18 June 1942, and the transfer took place on 20 June 1942. In Canadian service, these three tanks were designated Churchill Mk II (Special). The Churchill Mk II (Special) tanks were crewed and operated by No. 8 Troop, “B” Squadron of the Calgary Regiment. Although I have been unable to determine exactly when this occurred, sometime before 19 August 1942, the Oke flame‑throwing apparatus in T32422 was removed and fitted into T68875, another Churchill Mk II tank.

T32049 Tintagel, a Churchill Mk II of No. 10 Troop, “B” Squadron, 48th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, fitted with the Oke flame-throwing system. As can be seen in this photo, the rear mounted fuel container is connected up to a feed pipe which passed through the left pannier, which was itself connected to a flame projector in the front of the tank, as explained in the text. T32049 (fitted with the Oke flame-throwing system) was transferred to The Calgary Regiment’s charge on 20 June 1942, where under the name of Boar (No. 8 Troop, “B” Squadron), she was subsequently lost at Dieppe on 19 August 1942. For Dieppe, the rear mounted flame-thrower fuel reservoir, was enclosed within an armoured hexagonal shaped box. Source: Authors’ collection.

The use of the tank mounted “Oke” flamethrower by the Calgary Regiment at Dieppe, although rudimentary in nature, led to development of a more advanced model, of a tank-mounted flamethrower, again based on the Churchill chassis, which came to be known as the Churchill Crocodile, seen pictured here. The flame projector on the Crocodile, replaced the hull mounted machine gun, and had a range of 80 to 120 yards. The armoured fuel trailer, held 400 gallons of flame fuel and enough compressed nitrogen propellant for 80 one second bursts of flame through the flame projector. This trailer was connected to the tank by a three-way armoured coupling and could be jettisoned from within the tank if necessary. Source: Authors’ collection.

All three of these Churchill Mk II (Special) tanks T31862 Bull, T32049 Boar, and T68875 Beetle equipped with the Oke flame‑throwing apparatus took part in the raid at Dieppe on 19 August 1942. They were all destroyed before they could get into action. All three were carried on Tank Landing Craft 3 (No. 159):

– T31862 Bull was the troop commander’s (Captain B.G. Purdy) tank and was launched prematurely and drowned in 10 feet of water approximately 100 yards offshore.

– T32049 Boar, commanded by Sergeant J. Sullivan, in making a heavy landing from Tank Landing Craft 3, knocked her flamethrower fuel reservoir off her rear plate, but managed to cross the beach and get onto the promenade in the area of the Cassino. She remained mobile throughout the morning before being ordered back to the beach to cover the withdrawal. Once back on the shoreline, she was immobilized and acted as a pillbox.

– T68875 Beetle, commanded by Lieutenant G.L. Drysdale, also landing heavy, broke a track pin on her right track and remained immobilized on the shoreline, at the eastern end of Red Beach, also acting as a pillbox. Although the Churchill mounted, Oke flamethrower was rudimentary, by their presence at Dieppe, it is considered to be the first time that a British‑designed tank flamethrower took part in battle.

A closeup of the flame projector, which replaced the hull mounted machine gun, on the Churchill Crocodile. Source: Authors’ collection.

The Beach Track Laying Device:

The main beach at Dieppe, over which the Churchill tanks of the Calgary Regiment were to land, was entirely composed of rounded and oblong chert rocks which range from one to six inches in diameter, and was resistant to cracking or breaking. Tidal action, leave most of these chert rocks eventually resting on the beach surface at an angle of about 15 to 20 degrees. With these rocks being many metres in depth, vehicles would not be able to dig down to a solid base for traction. If a tracked or wheeled vehicle tried to climb up this slope, it would immediately dig itself down, and in the case of tracked vehicles, the strain of these chert rocks caught up between the drive sprocket and track, would cause the pins that held the track links together, to break, thus immobilizing the tank.

Another view of the “Beach Track Laying Device,” during the trails conducted by the Combined Operations Experimental Establishment. Note the position of the roll of chespaling, which was set approximately 24-inches, in front of the track. Source: MilAt photo archives.

Originally, to alleviate the foreseen problem of these chert rocks, it was planned to have four‑man teams of Royal Canadian Engineers, carried in each of the six Tank Landing Craft, that were scheduled to land in the first wave, who would run out ahead of the lead tanks, and roll out bundles of chespaling tracks. Chespaling was flexible roll fencing similar to wood slat snow fencing, but made with tough split slats made of chestnut. It was thought that by using chespaling, both wheeled and tracked vehicles would be able to get over the worst conditions of the chert rocks on the beach. Each of these bundles weighed approximately 250 pounds, were 25 feet long and could be wired together to form a continuous track, and could be moved around by the engineers to suit the later waves of incoming Tank Landing Craft. It was also found that chespaling enabled a tank to climb a 28-inch high wall.

A sketch of Major Sucharov’s design for the “Beach Track Laying Device,” dated 25 August 1942. Note the location of the rigid conduit, which had to be added for the protection of the wiring for the electrically fired small explosive charges, that released the rolls, and for those that jettisoned the whole device, and its path, back to the turret. Source: R.C. Harley.

Because of the weight of these chespaling bundles, and taking into account the probability of high casualties amongst the four‑man teams of Royal Canadian Engineers, from enemy fire, it was decided that an alternate method of laying out these bundles of chespaling tracks, ahead of the leading tanks of the first wave, be developed. Major B. Sucharov, an officer of the Royal Canadian Engineers (who commanded the engineers Beach Assault Party at Dieppe), was assigned to develop a device to enable the tanks, not only to get over the beach on landing, but to get over the seawall that separated the beach from the Promenade.

T31655 Buttercup, a Churchill Mk III of No. 9 Troop “B” Squadron, The Calgary Regiment, commanded by Sergeant J.D. Morrison, also one of five Churchill tanks of the regiment that was fitted with the “Beach Track Laying Device,” for the Dieppe raid. Having successfully landed and laid its chespaling and, having crossed the beach, wire, and seawall, it successfully jettisoned its beach track laying device, whereupon it engaged enemy targets on the west headland and in seafront buildings to the west of the Casino. Later, it returned to the beach below the Casino, where it took up a position on the water’s edge. It could not be destroyed by its crew prior to their withdrawal, due to the number of infantry wounded who had sought shelter from enemy fire on its seaward side. Note that there are no remnants of the beach track laying device, on her front, it having been jettisoned successfully. Source: Authors’ collection.

To this end, Major Sucharov came up with a carpet‑laying device using chespaling. He designed an apparatus that carried two separate rolls of chespaling, one for each tank track, which were suspended, about 24‑inches in front of each track, on a spindle that was supported by two short brackets above the front horns of the tank. The apparatus was mounted low enough to allow the tank commander a clear field of vision, and gave a clear field of fire for the turret mounted main armament and co-axial machine gun. On the inside and outside of each roll of chespaling, there was provided a 14-gauge metal disc shield, 3 feet in diameter to prevent the chespaling from fouling the brackets and spindle. Each roll of chespaling was 3 feet wide and 25 to 30 feet in length, with weighted ends that upon release, fell to the ground with the tank tracks themselves feeding out the rolls as the tank moved forward. The release of these rolls was controlled from the turret by means of an electrically fired small explosive charge. After use, the whole apparatus could be jettisoned by a small explosive charge, electrically set off from inside the turret.

From the Yukon series of exercises that were held at the tiny fishing harbour of West Bay on the coast near Bridport, Dorset, bundles of chespaling, used for laying a track to enable disembarking tanks to cross the beach, can be seen on the left. These bundles weighed approximately 250 pounds, were 25 feet long. Source: Authors’ collection.

Churchill tanks of The Calgary Regiment taking part in a series of exercises (Yukon I, 11/12 and Yukon II, 22/23 June 1942) that were held at the tiny fishing harbour of West Bay on the coast near Bridport, Dorset. In this photo, soldiers of the Royal Canadian Engineers, have rolled out bundles of chespaling tracks to enable the disembarking tanks to cross the beach. Source: Authors’ collection.

– T31124R Chief, a Churchill Mk I, carried in Tank Landing Craft 1 (No. 145), commanded by the Officer Commanding “C” Squadron, Major A. Glenn, prematurely laid its chespaling, and having jettisoned the beach track laying device, remained on the beach. For a time, Major Glenn kept his tank in a position from which he could observe the promenade and both flanks of the beach, when not obscured by smoke. After moving down the beach to the area in front of the Cassino, T31124R (Chief), returned the way it had came, and took up a position at the western end of the beached Tank Landing Craft 3 (No. 159) and turned broadside to the enemy, to protect the men sheltering behind the beached Tank Landing Craft.

– T68173 Cougar, a Churchill Mk III, carried in Tank Landing Craft 2 (No. 127), No. 13 Troop, “C” Squadron, the Troop Leader’s tank, commanded by Lieutenant T.R. Cornett, successfully crossed the beach and having laid its chespaling, crossed the seawall onto the Promenade, having only jettisoned part of its beach track laying device. Whereupon, after turning to the west, it was immediately hit by a 75‑millimetre round that jammed its turret. After this, it was only able to engage the tobacco factory with its 6‑pounder main armament from its position on the Promenade. Eventually, after having broken one track and having the other blown by enemy fire, it was destroyed by its crew, prior to their retiring back to the beach.

– T31135R Burns, a Churchill Mk I, carried in Tank Landing Craft 4 (No. 126), commanded by the Officer Commanding “B” Squadron, Major C.E. Page, removed its beach track laying device prior to landing, because it had been damaged. Having landed, Burns started to advance across the beach, but found its path obstructed by a tank trap consisting of a trench dug along the front of the esplanade wall. Upon attempting to avoid this obstacle, the tank’s right track was broken by enemy fire, which caused Burns, to be pulled into this ditch by the forward momentum of her left track, leaving her immobilized pointing downwards and unable to use its armament against enemy targets.

– T31655 Buttercup, a Churchill Mk III, carried in Tank Landing Craft 5 (No. 121), No. 9 Troop, “B” Squadron, the Troop Sergeant’s tank, commanded by Sergeant J.D. Morrison, successfully laid its chespaling and, having crossed the beach, wire, and seawall, jettisoned its beach track laying device, whereupon it engaged enemy targets on the west headland and in seafront buildings to the west of the Casino. Later, it returned to the beach below the Casino, where it took up a position on the water’s edge. It could not be destroyed by its crew prior to their withdrawal due to the number of infantry wounded who had sought shelter from enemy fire on its seaward side.