by Mark W. Tonner

The Matilda tank in Canadian Service

As stated earlier in Part 1, the main Canadian users of the Matilda tank were the 12th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), and 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)) (hereafter referred to as the Calgary Regiment, and the Three Rivers Regiment, respectively), of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, and No. 1 Canadian Ordnance Reinforcement Unit.

An example of the Infantry Tank, Mark III, Valentine, that the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade was to have been equipped with. Source: MilArt photo archive.

The 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, commanded at that time by Brigadier F.F. Worthington, was the first formation of the Canadian Armoured Corps (CAC) to arrive in the Untied Kingdom, landing on 30 June 1941. The General Officer Commanding, Canadian Corps (VII Corps), Lieutenant-General A.G.L. McNaughton had been anxious to add an armoured formation to his force in the Untied Kingdom at the earliest possible moment, and had encouraged the authorities in Canada to hasten the departure of Brigadier Worthington’s, 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade as much as possible. The brigade came under command of the Canadian Corps immediately upon its arrival in the United Kingdom. At this time, the brigade consisted of the following units:

An example of the new Infantry Tank Mark IV, Churchill (A22), that came straight from the Vauxhall Motors production line, that was issued to the Ontario Regiment on 10 July 1941, being inspected by Lieutenant-General A.G.L. McNaughton (hatless) and Brigadier F.F. Worthington (standing on the upper track run, with his back to the camera). Source: authors’ collection.

A column of Matilda tanks of the 12th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), led by T10163, a Mark IIA* Matilda III, which was taken-on charge of the Canadian Army Overseas, and issued to the Three Rivers Regiment, on 16 July 1941. Source: MilArt photo archive.

Headquarters, 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, CAC

- 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade Headquarters Squadron (The New Brunswick Regiment (Tank)), CAC

- 11th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Ontario Regiment (Tank)), CAC

- 12th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), CAC

- 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)), CAC

In the background is T10163, a Mark IIA* Matilda III, taken-on charge of the Canadian Army Overseas on 16 July 1941, and in the foreground is T17700, a Mark IIA* Matilda III, taken-on charge of the Canadian Army Overseas on 14 July 1941. Both of these tanks served with the Three Rivers Regiment, while in Canadian service. Source: MilArt photo archive.

Army tank brigades were independent formations under army control, as opposed to armoured brigades that were part of the armoured divisions. The sole role of the army tank brigades was infantry co-operation, and they were usually attached to an infantry division as the operational situation demanded. The tank battalions in the brigade were intended to provide intimate support to the infantry and were equipped with heavy ‘infantry’ tanks, in contrast to the lighter cruiser tanks used by the armoured brigades in the armoured divisions. At the time that 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade arrived in the United Kingdom, the war establishment of a Canadian army tank battalion, at this time, called for an authorized fighting strength of 58 infantry tanks to be held by each battalion, inclusive of six infantry tanks close support. The organization of an army tank battalion at this time was:

In the foreground is a Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support, armed with the 3-inch howitzer (with the co-axial 7.92-millimetre Besa machine gun mounted on it’s right). Although this particular tank (T29795) did not serve with the Canadian Army Overseas, the Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tanks that were issued to the Calgary, and Three Rivers Regiments, respectively, would have appeared as such. Source: IWM (H 11654).

a Battalion Headquarters

- with either four cruiser or four infantry tanks close support with a total strength of 17 all ranks

a Headquarters Squadron, consisting of:

- a squadron headquarters

- an intercommunication troop, with nine scout cars

- an administrative troop with a total squadron strength of 133 all ranks

three Squadrons, each consisting of:

- a squadron headquarters, with one cruiser or infantry tank, and two cruiser or infantry tanks close support

- five troops, with three infantry tanks each with a total strength of 154 all ranks per squadron for a total authorized tank battalion strength of 612 all ranks.

A Mark IIA* Matilda III of the Calgary Regiment, barring the War Department number T10159, which was taken-on charge of the Canadian Army Overseas, and issued to the Calgary Regiment, on 14 July 1941. Although not visible, this tank was named RINGER, and served with Battalion Headquarters of the Calgary Regiment, until being withdrawn from Canadian service and returned to the British on 1 December 1941. Source: MilArt photo archive.

The 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade was to have been equipped with the Canadian-built Infantry Tank, Mark III, Valentine, before leaving Canada. However, because of delays in Canadian tank production, Lieutenant-General McNaughton set out to persuade the British War Office to lend tanks to the incoming 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade. These would be replaced with Canadian-built tanks when Canadian production problems were overcome. With the added support of the British Army’s Commander of the Royal Armoured Corps, Major-General G. Le Q. Martel, he was successful in this endeavour.

Immediately upon arrival in the United Kingdom, 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade was able to draw equipment on a respectable training scale. The Ontario Regiment was equipped with the new Infantry Tank Mark IV, Churchill (A22), straight from the Vauxhall Motors production line, while the brigade’s other two battalions, the Three Rivers Regiment and the Calgary Regiment were issued with the Infantry Tank Mark IIA*, Matilda III (with twin Leyland diesel engines, a 2-pounder Ordnance Quick Firing gun Mark IX or Mark X, and a co-axial 7.92-millimetre Besa machine gun mounted in the turret, and fitted with the No. 19 Wireless Telegraph Receiving and Transmitting set (a radio set)). The British Directorate of Armoured Fighting Vehicles, also made arrangements, for officers and men of these two regiments, to attend courses on the Matilda, that they ran at three of the firms producing this tank. Each of these courses was five days in length, and were ran at the Vulcan Foundry Ltd., site at Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire, at the Grantham, Lincolnshire, site of Ruston & Hornsby Ltd, and at the John Fowler & Co., site at Leeds, West Yorkshire.

Right-hand side view of T10159, RINGER, a Mark IIA* Matilda III, of Battalion Headquarters, the Calgary Regiment, during a demonstration of ‘Tank Hunting’ with a platoon of the 3rd Canadian Divisional Infantry Reinforcement Unit, in the vicinity of Headley, Hampshire, on 9 October 1941. Source: authors’ collection.

As with the Churchill tanks that the Ontario Regiment began to receive, the Matilda tanks that began being issued to the Three Rivers Regiment and the Calgary Regiment, were received from the British through No. 1 Canadian Base Ordnance Depot, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, located at Bordon Camp, Hampshire. No. 1 Canadian Base Ordnance Depot, as with the Churchill tanks, took the Matilda tanks onto Canadian charge, and after inspecting them for any mechanical faults, and insuring that all the appropriate tank tools and equipment for each individual tank were in place, and if not, noting what deficiencies (shortages) there were, passed them onto the charge of the receiving unit.

By the end of July 1941, both the Three Rivers Regiment, and Calgary Regiment, held between them, 29 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks, while Headquarters 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, held one Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tank, with a 3-inch howitzer in the turret. The war diary of the Three Rivers Regiment states that as of 31 July, they held on strength 11 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks, thus leaving ten, as being held on strength of the Calgary Regiment.

During the month of August 1941, a total of 18 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks were issued between the Three Rivers Regiment, and Calgary Regiment, with the Three Rivers Regiment receiving two, while the remainder were issued to the Calgary Regiment. September saw the issue of an additional 31 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks, to the Three Rivers Regiment, and Calgary Regiment, with the Three Rivers Regiment receiving 21, while the Calgary Regiment received the remaining ten. Additionally, the Calgary Regiment was issued with one Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tank during the month of September. Of note, as of 30 September 1941, of the 71 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks issued to date, to the Three Rivers Regiment, and Calgary Regiment, 61 of these are shown on the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade Readiness Return as ‘in action,’ (battle ready) with the remaining ten shown as being ‘out of action,’ due to various forms of mechanical failure, etc. Both of the Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tanks that had been issued to units of 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, to date, were also shown as ‘in action.’

As mentioned at the end of Part 1, the Mark IIA Matilda II (powered by twin AEC diesel engines), and the Mark IIA* Matilda III (powered by twin Leyland diesel engines), could only be identified as such from the rear, by the simple fact, that the Mark IIA Matilda II had only had one exhaust pipe running down the left side of the engine deck, while the Mark IIA* Matilda III had an exhaust pipe running down each side of the engine deck. As can be seen in this photo, other then the exhaust pipe(s), both the Mark IIA Matilda II, and the Mark IIA* Matilda III were identical in appearance when viewed from the front. The top image is of a Mark IIA Matilda II (Source: IWM (KID 782)), while the bottom image, is of a Mark IIA* Matilda III (Source: IWM (MH 9264)).

The month of October 1941, was the last month in which the Mark IIA* Matilda III tank, was issued to units of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, with a total of 18 having been received by months end. The war diary for the Three Rivers Regiment states that as of 31 October 1941, out of an entitlement of 45 infantry tanks, they held on strength a total of 42 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks, while the war diary of the Calgary Regiment, reflects that out of an entitlement of 45 infantry tanks, they held on strength a total of 4 Mark IIA* Matilda III and two Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tanks. Of the 89 Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks held by the Three Rivers Regiment, and Calgary Regiment, as of 31 October, the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade Readiness Return reflects that 84 of these were ‘in action,’ with the remaining five as being ‘out of action.’ Both the Mark IIA* Matilda III Close Support tanks, held by the Calgary Regiment (one with “A” Squadron headquarters, and one with “C” Squadron headquarters), were shown as being ‘in action,’ on the Readiness Return of 31 October 1941.

Continued in Part 3 – The Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12) in service with the Canadian Army Overseas

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars, below.

by Mark W. Tonner

Introduction

The Matilda II (A12) was an ‘Infantry’ (or ‘I’) tank which was specifically designed to fight in close support of infantry operations, or as the British General Staff defined it, “the role of the infantry tank is the assault in the deliberate battle in conjunction with other supporting arms.” For this role, the requirements for an infantry tank, as the British General Staff saw it, were that the tanks have heavy armour, powerful armament, good obstacle-crossing performance, with reasonable range and speed. It was the second in the British series of infantry tanks, with its predecessor being, the Infantry Tank Mark I, Matilda I (A11).

A 3/4 front view of the pilot model of the Infantry Tank Mark I, Matilda I (A11), designated A11E1 (and baring the War Department number T1724, and the Road Registration number CMM 880), which was delivered for trials in September 1936, to the British Mechanization Experimental Establishment, Farnborough, Hampshire. Source: IWM (KID 68).

Mechanization Experimental Establishment. By November 1939, the limitations of the solitaire machine gun armament (either one .303-inch Vickers machine gun, or one .50-inch Vickers machine gun) of the A11, and the need for better armoured protection of the crew, and for greater firepower, lead, to the design of the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), since to incorporate the needed improvements, was not feasible with the basic A11 design. Source: IWM (KID 158).

A brief note on the nomenclature (names) used by the British for the various variants of the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12). The suffix letter ‘A’ denoted a change in the armament of the co-axial machine gun, from that of the .303-inch Vickers machine gun, to that of the 7.92-millimetre Besa machine gun. The asterisk denoted that the power units, had been changed over to Leyland twin diesel engines, from that of AEC twin diesel engines.

A 3/4 rear view of the pilot model Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), designated A12EA1 (barring the Road Registration number HMH 786). This pilot model was delivered for trials in April 1938, to the British Mechanization Experimental Establishment, Farnborough, Hampshire. Source: IWM (KID 465).

A right-side view of the pilot model Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), A12EA1, while undergoing trails at the British Mechanization Experimental Establishment. A12EA1, was powered by twin commercial AEC straight six-cylinder water-cooled diesel engines, making the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), the first British tank in service to use diesel engines. Source: IWM (KID 1542).

Prior to June 1940, the Infantry Tank Mark II, the Infantry Tank Mark IIA, and the Infantry Tank Mark IIA*, had been simply known as the A12. As of 11 June 1940, to differentiate the various changes in armament or power units, the nomenclature was further broken down by designating the Matilda, whose co-axial machine gun was that of the .303-inch Vickers machine gun, and whose power units were AEC twin diesel engines, the Infantry Tank Mark II. Those with the 7.92-millimetre Besa co-axial machine gun, and whose power units were AEC twin diesel engines, were designated the Infantry Tank Mark IIA, while those with the 7.92-millimetre Besa co-axial machine gun, and whose power units were Leyland twin diesel engines, was designated the Infantry Tank Mark IIA*. As of July 1941, the nomenclature of the Matilda was changed yet again. The Infantry Tank Mark II, was designated the Matilda I, while the Infantry Tank Mark IIA, was designated the Matilda II, and the Infantry Tank Mark IIA*, was designated the Matilda III.

The main Canadian Army Overseas users of the Matilda tank were the 12th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), and 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)), of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, and No. 1 Canadian Ordnance Reinforcement Unit.

British Development and Production of the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12)

The need for better armoured protection of the crew, and for greater firepower, lead to the design of the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), since to incorporate the needed improvements was not feasible with the basic Infantry Tank Mark I, Matilda I (A11) design. The new design for the A12, drawn up by the British Mechanization Broad, called for increased armour thickness, a commercial AEC straight six-cylinder water,-cooled diesel engine, and heavy armoured side skirts to protect the suspension. It also called for a crew of four, as opposed to the A11 crew of three, and initially, the design called for a turret mounting two co-axial machine guns as the main armament. This was quickly changed to a three-man turret mounting a 2-pounder anti-tank gun and a co-axial Vickers machine gun. At the time, in view of the A12’s proposed role as that of an infantry tank in close support of infantry operations, there were some who advocated that a main armament capable of firing high explosive rounds should be mounted. The British General Staff however, declared that the Matilda II (A12) was to protect the infantry from enemy tanks, and thus the 2-pounder anti-tank gun, which at the time was the best anti-tank gun in the world, was to be used as the main armament. However, an agreement was reached whereby the turret should be made capable of mounting a 3-inch howitzer1 as an alternative to the 2-pounder anti-tank gun, which was only envisioned at the time, and that the howitzer was only required to fire smoke rounds as cover for gun tanks.

Work is finished off on a Matilda tank, at a factory somewhere in the United Kingdom. Note the grinding down of rough surfaces, which is being done by a worker on the rear deck. Source: IWM (D 9191).

In November 1936, Vulcan Foundry Ltd., of Warrington, Lancashire, was directed to produce a wooden mock-up of the A12 design. The mock-up was inspected in April 1937, by which time the British Mechanization Broad had decided to use twin AEC diesel engines coupled together instead of just one AEC diesel engine. Each engine was capable of delivering a maximum 87-brake horsepower2 at 2,000-rotations-per-minute. The Matilda II (A12) was the first British tank in service to use diesel engines. Having accepted the mock-up, Vulcan Foundry was directed to produce two pilot models of mild steel construction (with the assigned designations of A12EA1 and A12E2, bearing the War Department numbers T-3431 and T-3432, respectively – Contract No. T.3951, dated 25 May 1937). Construction of the pilot models was however held up by the delay in the delivery of component parts and it wasn’t until April 1938, that the A12EA1 (War Department number T-3431) pilot was delivered for trials to the British Mechanization Experimental Establishment, at Farnborough, Hampshire. Trials were generally satisfactory, but some small modifications were needed to the gearbox, suspension and cooling system. In June 1938, an initial order for 140 Matilda II (A12) tanks was placed with the Vulcan Foundry Ltd., followed in August by an order for 40 more which were manufactured at the Grantham, Lincolnshire, site of Ruston & Hornsby Ltd., under Vulcan, who were responsible for overall production. As the threat of war became a reality other firms, all operating under the leadership of the Vulcan Foundry Ltd., began the manufacture of the Matilda II (A12). These firms were, the John Fowler & Co., of Leeds, West Yorkshire, the North British Locomotive Company of Glasgow, Scotland, Harland & Wolff of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and the London, Midland & Scottish Railway Company at their Horwich Locomotive Works site. Vulcan Foundry Ltd.’s own production line for Matilda II (A12) was located at their Locomotive Works, Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. Generic fittings and electrical equipment that each Matilda tank was to have, was supplied to the firms working under Vulcan’s direction from a vast number of suppliers within the United Kingdom.

The view of a busy Matilda tank assembly line, at a factory somewhere in the United Kingdom. Source: IWM (P 58).

As noted in the text, the Mark II Matilda II, and the Mark IIA Matilda II, that were powered by twin AEC diesel engines, could be identified from the rear, by the simple fact, that only one exhaust pipe ran down the left side of the engine deck, as can be seen here on the rear of T10291, a Mark II, Matilda II. Source: authors’ collection.

The most significant factor in the A12 design, was its armour protection, which at the time could withstand any known anti-tank gun and most other known forms of artillery. The Matilda II (A12) tank was not easily massed-produced. The hull of the Matilda II (A12) was constructed differently than those of most other tanks in that it was built up of specially shaped armour and mild steel castings, and from armour steel plates secured together by rivets and screws, which were so constructed as to form a rigid structure, whereas other tanks used a frame on to which plates were built. The size and shape of its mixture of armoured rolled plates and castings, gave the Matilda II (A12) great strength but demanded a vast amount of specialist skills during the manufacturing process. In areas where these armoured castings were too thick they had to be ground away from the inside, a very time consuming task which required skilled craftsman to carry out. In addition to the hull proper, armoured side protection (skirting) plates carried from the hull on cast steel brackets were provided to give additional protection from gun fire. The interior of the hull was divided into three compartments, the driver’s compartment, the fighting compartment, and the rear compartment (or engine housing) which housed the power units (engines) and transmission gear. Side panniers were provided along the hull sides above the track tunnels. Mud chute plates, designed to protect the suspension gear from mud and stones carried over by the tracks, were provided between the hull sides and the armoured side protection (skirting) plates.

As noted in the text, those Matilda tanks that were powered by twin Leyland diesel engines (the Mark IIA* Matilda III onwards), could be identified by an exhaust pipe running down both sides of the engine deck, as seen in this photo. Source: authors’ collection.

Just as the Matilda II (A12) had entered production, the British War Office came to the decision that the water-cooled .303-inch Vickers machine gun, carried by all British armoured vehicles at that time, would be replaced by the British built version of the Czech ZB air-cooled 7.92-millimetre Besa machine gun, which became the principal co-axial machine gun used in British tanks. This caused a modification in design of the Matilda turret, not only in the mantlet, but also in the elimination of the outlet for the discharge of vapour from the water-cooled Vickers. With the removal of the Vickers the electrically driven pump that maintained its water supply went with it, with this pump’s circuit being modified to provide for an extractor fan in the turret roof. With these modifications the tank became known as the Infantry Tank Mark IIA or the Matilda II. Also, shortly after the beginning of production of the Matilda II (A12), a search for an alternate power unit had begun. Vulcan Foundry Ltd., modified the second pilot model, A12E2 (War Department number T-3432), to fit twin Leyland 6-cylinder diesel engines, each of which was capable of delivering a maximum of 95-brake horsepower. Once the Leyland 6-cylinder diesel engine was accepted, the various contractors involved in the production of the Matilda, under the parentage of Vulcan Foundry Ltd., were ordered to fit them into future models of the Matilda. This was designated the Infantry Tank Mark IIA* or the Matilda III (these were also known as the Matilda Star tank). The twin Leyland diesel engine Matilda III was the first to mount the alternate main armament of a 3-inch howitzer in the turret. These were designated the Infantry Tank Mark IIA*, Matilda III Close Support

Contract No. T.9958 (dated 12 June 1940), to the North British Locomotive Company, under which the highest number (18) of Mark IIA* Matilda III tanks issued to the Canadian Army Overseas was built. Source: authors’ collection.

As a point of interest, the Mark II Matilda II and the Mark IIA Matilda II, powered by twin AEC diesel engines, could be identified from the rear by the one exhaust pipe which ran down the left side of the engine deck, with the other emerging from underneath the hull. Those powered by twin Leyland diesel engines (the Mark IIA* Matilda III onwards) had an exhaust pipe running down both sides of the engine deck. On all Matildas these exhaust pipes ended in a pair of silencers (a device for reducing noise) mounted across the back of the hull, beneath the overhanging rear deck.

Over all, by August 1943, when production of the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12) ended, the British had built approximately 2900 (inclusive of the two pilots) Matilda II (A12) tanks.

Contracts under which Matilda tanks issued to the Canadian Army Overseas, were built:

Contract No. T.5115 (dated 11 June 1938) (the initial contract) – built by Vulcan Foundry Ltd.

Contract No. T.5693 (dated 24 October 1938) – built by John Fowler & Company Ltd.

Contract No. T.5741 (dated 19 April 1939) – built by London, Midland & Scottish Railway Company

Contract No. T.6904 (dated 1 July 1939) – built by North British Locomotive Company

Contract No. T.6905 (dated 19 April 1939) – built by Harland & Wolff Ltd.

Contract No. T.6906 (dated 19 April 1939) – built by John Fowler & Company Ltd.

Contract No. T.6907 (dated 19 April 1939) – built by Ruston & Hornsby Ltd.

Contract No. T.6929 (dated 19 April 1939) – built by Vulcan Foundry Ltd.

Contract No. T.7717 (dated 26 August 1939) – built by North British Locomotive Company

Contract No. T.9862 (dated 12 June 1940) – built by London, Midland & Scottish Railway Company

Contract No. T.9958 (dated 12 June 1940) – built by North British Locomotive Company

Contract No. T.9959 (dated 12 June 1940) – built by Ruston & Hornsby Ltd.

Contract No. T.311 (dated 26 July 1940) – built by Vulcan Foundry Ltd.

Notes:

1. A relatively short barreled gun for firing shells at a high angle.

2. Brake horsepower is the measure of an engine’s horsepower before the loss in power caused by the gearbox and drive train.

Continued in Part 2 – The Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12) in service with the Canadian Army Overseas

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below.

by Major (Ret’d) Paul Harrison, CD

G4 Supply SSF/2 CMBG 1995

Following the 1995 demise of the Canadian Airborne Regiment, it was decided that the Special Service Force (SSF) was to be re-aligned to closely match 1 and 5 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Groups. This resulted, on 24 April 1995, in the creation of 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (2CMBG), based on the former SSF.

The author had been posted to the Force G4 Supply position in December 1994 and one of his secondary duties included supply requirements that fell outside either the unit level or the national (NDHQ) level of responsibility.

In the spring of 1995 the author was advised that the Brigade Commander wanted a new Brigade patch in wear for a parade to be held in the fall of 1995. In addition to the procurement of the badges, the Base tailor shop would have well over 3000 tunics to re- badge with the associated time requirements.

Although National Defence Headquarters understood the need for quick action they advised that the procurement of new brigade patches would not be possible for at least eighteen months due to other priorities. In light of this it was agreed that NDHQ would provide the funding while the author would raise a contract with support from Base Supply.

Calls were made to known Canadian Forces badge suppliers including Grant Emblem in Toronto, Ontario. In a June of 1995 meeting they reviewed the drawings supplied by the Directorate of Heritage and History and agreed to produce five samples for each of the Distinctive Environmental Uniform (DEU) Land and the Army Garrison Dress Uniform. The cost of the samples was approximately $500. The samples, once received, exhibited excellent work and the initial concern was the degree of detail.

First set of samples included white detail for the bear’s eyes and claws as well as the bear facing to the right. Courtesy Bill Alexander

Both the DEU and Garrison versions had a black bear superimposed onto a gold arrowhead and, in keeping with the artwork provided by DHH, included details such as white claws and an eye. The blessing of the Force RSM, CWO Douglas, was obtained although he subsequently directed that it was critical the bear, moving left to right, be reversed. From a heraldic point of view this was not acceptable, so among the changes transmitted to Grant Emblem was a corrected direction, the removal of the white stitching and amplification of the correct colours. The 2CMBG Commander argued against the change of direction of the bear but was over-ruled by heraldic rules governing badge design within the CF.

Second set of samples corrected the initial concerns but the colours were incorrect, especially the Garrison Dress badge which did not display the ‘subdued’ colour expected. Courtesy Bill Alexander

It was agreed that the supplier would produce another set of samples and, in July a second set of samples, for both DEU and Garrison dress, was received. The DEU versions were basically correct, although the gold arrowhead colour was a shade off, but the Garrison Dress patches were incorrect, as the arrowhead was still in bright gold and not the subdued colour required. The manufacturer was contacted and a third set was produced. These arrived in August and met all the requirements. At that point sealed samples were produced and sent to the DHH and an order for 7000 examples of each badge was placed. This initial order was based on roughly two patches of each type for all army personnel in 2CMBG.

Production examples showing the DEU patch on the left and the Garrison Dress patch on the right. Courtesy Bill Alexander

CF regulations covering the wear of brigade patches stipulated that these were to be worn on the right sleeve. Once the bear was moving in the heraldically correct direction it could be interpreted as ‘running away’ from battle – in fact 5 Brigade was the butt of good-natured ribbing within the army that the lion depicted on their patch was running away, or facing the rear. This resulted in the brigade commander ordering the formation patch to be worn on the left sleeve only and it remained this way for at least the first year.

Officers of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, circa 1997, shown wearing the 2CMBG formation badge on the left sleeve in order to ensure that the bear was facing forward. This practice was tolerated for only a couple of years by NDHQ. DND photo SUC97-87, courtesy Bruce Graham

One framed set, consisting of the first and second sets of samples, along with SSF patches, was presented to the Base Museum at CFB Petawawa. This included all of the original paperwork that had been created and was donated with the understanding that they would remain on display, with the documentation ensuring a recorded history of the procurement. The remaining patches were released among a few collectors and the G4 at that time.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Andrew B. Godefroy

© 2014

The wars of the 1990s proved that nations capable of leveraging space-based platforms in operations enjoyed a decided advantage over their adversaries. Allied success in the 1990-91 Gulf War, for example, involved the successful military application of the Global Positioning System (GPS), space-based imagery, theatre missile warning and defence, satellite communications, and space situational awareness. These space systems continued to evolve throughout the 1990s, and towards the end of the decade the Canadian Forces (CF) undertook a series of its own initiatives designed to operationalize various strategic level space-based assets within its field forces. These efforts included the creation of an experimental CF Joint Space Support Team (JSST) within the CF Joint Operations Group (CFJOG) at Kingston, Ontario in 2001.

Formed in early 2001, the JSST initially consisted of only two members (1 officer, 1 NCO), with a third junior NCO joining the team later in the summer of 2001. Throughout its brief existence (2001-2004), the original JSST never included more than four members at any time, typically 2 officers and 2 senior NCOs. Each member was responsible for specific area of expertise. The author served as the only officer commanding throughout this period.

As an experimental team focused on integration, testing, and evaluation, in addition to technology demonstrations and real world operational support, the JSST was also tasked to trial a variety of new combat uniform patterns and badges. The first members arrived in their posts still wearing the Cold War era olive drab combat uniforms, but this soon changed when the CF introduced the new CADPAT combat clothing the following year. Still, even though the team operated in a defined area within the CFJOG headquarters, unlike the CF Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) officers and NCOs it remained difficult to visually discern at a glance exactly who the JSST members were.

The idea of creating a specific insignia identifier to be worn by JSST members was first raised by the CFJOG Chief of Staff at a weekly coordination meeting in April 2001. The CFJOG itself had just recently formalized its own new crest and other specialized units then under command, such as the CF DART, were already wearing special insignia in the headquarters on olive drab brassards. It was therefore suggested that while the JSST was attached to the CFJOG, it should adopt a similar practice for ease of identification. The author forwarded the request back to the Directorate of Space Development (D Space D) in Ottawa, which after a short period of consideration replied favourably to the idea.

Insignia Concepts

The author was subsequently tasked to propose a small number of designs for consideration. There were caveats applied of course. D Space D had expressed a desire that in order to best promote both the team and the project that it was a part of the final insignia design should easily stand out from other traditional military styles. D Space D therefore directed early on to come up with something unique and therefore to avoid using the typically popular 4-inch diameter circular patch as the basis for the team’s insignia. The author consulted various sources for other ideas, including the variety of insignia then in use by Canada’s civilian space program. This proved helpful as space programs employed a wide variety of shapes depending on the program, project, or mission.

The JSST insignia with D Space D’s own directorate logo was also designed by author, in 1999, while serving at NDHQ. Author’s collection

D Space D also directed that any and all design proposals should align the JSST insignia with D Space D’s own directorate logo in order to strengthen the Canadian defence space community’s overall ‘brand’. Several scribblings and conversations later the author arrived at a final proposal for the JSST insignia. Like all Canadian military patches it seemed necessary to include a maple leaf. With this in mind the remainder of the design was inspired by a report the author had recently written for D Space D simply titled ‘Maple Leaf in Orbit’.

Production and Use

The final design was approved during the summer of 2001, and local companies were consulted soon after to produce the patch for the team. Due to the fact that the JSST was an experimental unit and would only ever consist of a very small cadre of perhaps less than a half dozen personnel, the JSST insignia were produced in very limited numbers. A single proof of design patch was made for the author’s approval – this unique patch has a black backing and special tag – with all remainder production full colour and olive drab patches having a off-white cloth cover backing (Figure 5). A private contractor made a total of 100 patches in each variety. Initially worn on a brassard in similar fashion to the DART staff members, each team member received two full colour and two subdued pattern brassards to wear on the new CADPAT uniform.

The brassard worn with the subdued badge by team members when on Ops and in CadPat. When the team switched to flight suits the badge was changed to a pattern with Velcro backing. Author’s collection

As part of the larger CF joint experiment, in early 2002 the JSST was directed to begin trialing an air force flight suit uniform in lieu of army CADPAT for the remainder of the year. This resulted in the brassard being replaced by Velcro backed insignia that could be applied to the suits. Typically full colour insignia was worn on these uniforms while in garrison, switching to subdued pattern patches when on exercise or in support of operations. These outfits proved popular with the team as well as the joint community, and they remained in use until the end of the initial trial in 2004.

Final disposal and reproductions

Each member of the JSST received approximately a dozen each of the colour and subdued pattern insignia for the various uniforms tested throughout the project; this accounted for about half of the total number produced. The remaining patches were dispersed amongst various CF personnel, the two USAF exchange officers attached to the project between 2001-2004, as well as a handful of DND civilian project managers and defence scientists also involved with the project. A very small number were handed out as tokens of appreciation during various official visits to the team, thus a few have made their way into the United States and elsewhere. When the initial team was stood down in 2004, none of the patches remained in stocks and no more were produced. Interestingly, the original JSST design is still in use by DND today, except that it has been subsequently altered to reflect the acronym of a new joint organization with a different name assigned within DND’s Director General Space (DG Space).

Perhaps what is more interesting even is the fact that in recent years the author has seen various reproductions of both the colour D Space D patch and the colour JSST patch appear for sale, with a few appearing from time to time on E-bay and other auction or militaria websites. These generally tend to be of much poorer quality than the originals, and since there was ever only a single batch of originals made, any other known design variants of the patches illustrated in this article may be considered to be reproduction patches.

During the brief existence of the CFJOG from 2000 to 2005, both the DART and the JSST stood out from the remainder of the headquarters group in terms of distinct insignia designed for a specific purpose. Because it still exists today as a special organization much has been written concerning the insignia of the DART, while the original JSST has since fallen entirely into total obscurity. This short article has sought to rectify that imbalance just a little, by shedding new light on the worn insignia of one of the modern CAF’s little known units.

by Clive M. Law

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was formed in December 1939 to address the need for aircrew training to meet the needs of the Commonwealth. Although not limited to Canada the great majority of schools and graduates were trained in Canada. At the plan’s high point in late 1943, an organisation of over 100,000 administrative personnel operated 107 schools and 184 other supporting units at 231 locations all across Canada.

With the outbreak of the Second World War many flying clubs, including the SCFC saw their resources being stretched to the limit. This was due to new members hoping to gain qualifications in an attempt to automatically qualify for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The staff of the schools were not members of the Royal Canadian Air Force but were civilians hired under contract by the individual school. Nonetheless, as they were in ‘command’ of the students during training the wear of a uniform was supported by National Defence Headquarters. Most schools standardized on a dark blue pattern although some chose a charcoal grey. The cut was similar to the RCAF Service Dress. In the case of 9 EFTS, the initial uniform was of khaki material and only changed when the BCATP standardized on blue.

Opening day at #9 EFTS with Instructor Charlie Harrod in the middle. Note that the uniforms lack any insignia as they were not designed yet. Cam Harrod collection

The use of insignia proved to be challenging as NDHQ regulations (supported by an Act of Parliament in 1943) made the wear of military uniforms and insignia by civilians illegal. This resulted in the schools designing and producing their own insignia which, by definition, did not require NDHQ approval. For this reason identifying the badges worn by these schools is difficult for modern collectors.

Staff of No.9 EFTS at St. Catharines. Note that there are no Engineering staff included in this photo. MilArt photo archives

Thanks to the Canadian Flying Clubs Association there was some standardization of insignia. These included separate cap badges for flight instructors and engineering staff, as well as different breast insignia (calling them “wings” would be a stretch).

Nonetheless, some schools developed their own badges. One of these was No. 9 EFTS at St. Catharine, Ontario.

This school was established after Murton A. Seymour, president of the St. Catharines Flying Club (SCFC) travelled to Ottawa in 1939, in an attempt to have the government support air training through existing flying clubs. This goal was realized on August 12, 1940 and an order was received from Ottawa announcing that the opening date of October 15, 1940 and that the school was expected to accept 28 students.

The insignia for No. 9 EFTS borrowed heavily from the RCAF in that it used a cap badge similar to the officer’s pattern, full wings for flying instructors and a single wing for ground instructors. This latter badge has the appearance of the First World War Observer’s badge.

Continuing the separation between skills, the engineering staff wore a different cap badge and wore breast insignia that could be mistaken for trade badges.

Not wishing to be left out, administrative personnel also wore a badge consisting of stylized wings with the letter ‘A’ in the centre. The manager of the school wore a similar badge but with the letter ‘M’ to denote his higher status.

F. Pattison, Manager of the school and A. Parsons, Secretary-Treasurer. Note the unique wings worn by these two individuals. MilArt photo archives

A stylized “9” emulating the First World War Observers badge. This was worn by non-flying personnel. Cam Harrod collection

No. 9 EFTS was formally disbanded on January 14, 1944. When the school closed it had accepted 2,468 student pilots. Of these, 1,848 graduated from the program. The total air time for the school was 134,011 hours.

The study of the uniforms and insignia of the BCATP is a fertile ground and has not been adequately addressed although there are a few dedicated collectors who are actively researching this insignia. The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance and photos provided by Cam Harrod, whose father Charlie Harrod was an instructor at #9 EFTS, St Catharines.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below. You can also leave comments by using the link at the bottom of the page.

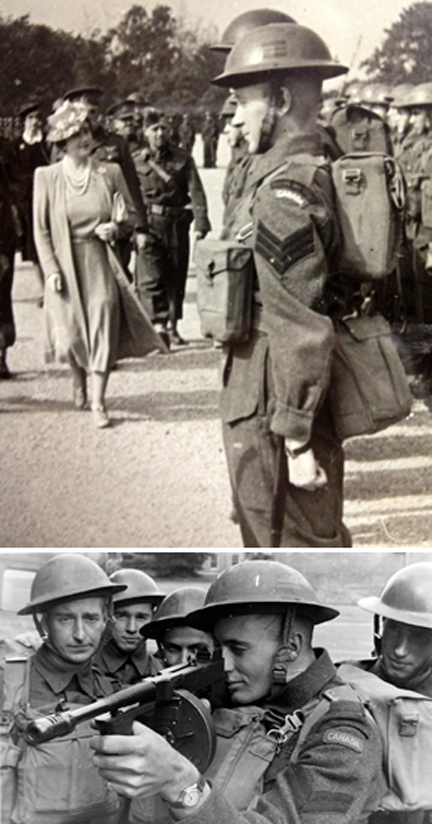

by Edward Storey

The use of British designed body armour by the Canadian Army in World War Two is not well known and few examples have survived in museums and private collections. Brian L. Davis gives an excellent overview of the British Medical research Council (MRC) Body Armour in his book “British Army Uniforms & Insignia of World War Two”. Tracing the use of MRC Body Armour can be very difficult as photographs of MRC Body Armour in use during World War II are scarce since the prescribed method of wear was underneath the Battledress (BD) uniform.

From 1940 until 1942 the British Army and the Medical Research Council (MRC) worked hard at developing a set of body armour that could fill the needs of all three services had to be considered as well as designing a piece of equipment that could be worn comfortably.

The material used in this body armour was the same 1mm manganese steel found in British helmets. The body armour, weighing 3½ pounds, was designed so that its three pieces covered the vital parts of the body.

“After field trials on 5000 sets of armour, official use was given in April 1942 to introduce the body armour into the British Army. Originally 500,000 sets were to be produced although eventually only 200,000 were actually produced with 79,000 being issued. The Royal Air Force took the bulk at 64,000 and the 21st Army Group the remaining 15,000.”[i]

Simon Dunstan also gives a rather detailed description of the testing that the MRC Body Armour was subjected to in his book “Flak Jackets 20th Century Military Body Armour“.

“The body armour, when tested, proved favourable and withstood a .38 bullet at five yards, a .303 bullet at 700 yards and a ‘Tommy Gun’ single shot (.45 cal) at 100 yards. After further field exercises it was found that the armour, although well padded, tended to cut into the soft-skin areas of the body causing chafing, with the result that violent and rapid movements were significantly impaired. Moreover, it causes a man to perspire so profusely that his powers of endurance were affected.”[ii]

Production was reduced from 500,000 sets to just 200,000 sets because the steel required was the same as that of Steel Helmets which had priority. Of this production,

“Some 12,000 sets were sent to 21 Army Group, where the major portion was allocated to the Airborne Divisions, with smaller quantities to the Canadian Army, SAS Troops and the Polish Parachute Brigade… The MRC Body Armour was rarely used in action; the only confirmed occasion was by the Airborne Forces during Operation ‘Market Garden’.”[iii]

Canadian Army use of the MRC Body Armour is not well documented and little known. By studying World War II photographs and by talking to veterans, a pattern starts to emerge.

Reconstruction photographs showing a rifleman with The Royal Rifles of Canada modelling the MRC Body Armour. Author’s collection

A 3rd Canadian Infantry Division veteran, Sapper Jack Fleger from 6 Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers, fought in North-west Europe from the Normandy Invasion in June 1944; until the fighting around the Breskins Pocket, Belgium, in October 1944 when he was wounded in the face. For the Invasion of Normandy, Mr. Fleger waded ashore with the following equipment: 1937 Pattern Web Fighting Order, Mine Detector, Life Belt, Number 4 Mark I* .303 Lee-Enfield and MRC Body Armour. The Body Armour was to protect him from mine blasts, he dumped the Body Armour shortly after coming ashore.

Lieutenant John J. H. Connors was a Stretcher Bearer Officer in the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade (CIB) of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division who fought in North-west Europe from the Capture of Caen in July of 1944, until the end of hostilities in May of 1945. The 4th CIB consisted of the following Infantry Regiments: The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, The Royal Regiment of Canada and The Essex Scottish. Lieutenant Connors was one of two Stretcher Bearer Officers in the 11 Canadian Field Ambulance, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, and they usually worked in conjunction with the lead Infantry Battalions.

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière using a rubber raft to cross the Ijssel River, Zutphen, Netherlands, 7 April 1945.

The nature of Mr. Connors work was very hazardous and in the Caen area he and his men managed to get some sets of MRC Body Armour from casualties who no longer needed them. He wore the armour throughout the North-west Europe Campaign and it is still in his possession. Mr. Connors even wore the Body Armour while sleeping in trenches to help cover the exposed portions of his body. He noted that some of those he saw wearing the MRC Body Armour were primarily more concerned with covering their reproductive organs than any other part of the body.

Another veteran of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division I have spoke to also stated that he wore the MRC Body Armour. I did not record his name, but in conversation he mentioned that he served with the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, 6th CIB in North-west Europe. He mentioned that MRC Body Armour was used on specific occasions; usually by the lead sections in the assault; and that the body armour gave those that wore it an added sense of security.

Detail Photograph of MRC Body Armour from page 62 of “The Brigade” – Le Reg de Maisonneuve, Major Jaques Ostiguy and his headquarters section. Author’s collection

Photographic and anecdotal evidence tends to point to the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division as the primary user of MRC Body Armour from the time they arrived in theatre in July, 1944 until the end of the war in May, 1945. Canada fielded five divisions in World War II, why the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division had what appears to be almost exclusive use of the British MRC Body Armour is open for more investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance with this article:

Major John. J. H. Connors (Ret.)

Jack Fleger, who passed away in November 1989 as a result of wounds received while on active serve in Europe

Guy Lafontaine

My wife Loretta.

SOURCES

Copp, Terry, “The Brigade – The Fifth Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1939-1945”, Stoney Creek, 1992.

Davis, Brian L., “British Army Uniforms & Insignia of World War Two”, London, 1983.

Dunstan, Simon and Ron Volstad, “Flak Jackets 20th Century Military Body Armour”, London, 1984.

Whitaker, W. Denis and Shelagh, “Tug of War – The Canadian Victory That Opened Antwerp”, Toronto, 1984.

NOTES

[i] Brian L. Davis, “British Army Uniforms & Insignia of World War Two” (London, Arms and Armour Press, 1983), p 246-247.

[ii] Simon Dunstan and Ron Volstad, “Flak Jackets 20th Century Military Body Armour”, (Osprey Men-at-Arms Series, 1984, Number 157), p 8-9.

[iii] Op. Cit.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below. You are also encouraged to leave a comment.

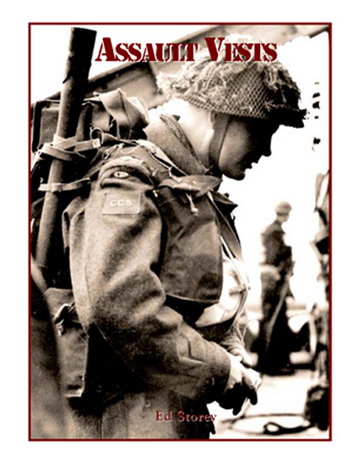

“Assault Vests” by Ed Storey is now available from Service Publications

by Clive M. Law

The Regiment of Canadian Guards joined the ranks of the Canadian Army on 16 October 1953, amid a fair measure of reluctant acceptance by existing regiments. The Canadian Guards (Cdn Gds) also faced opposition from the press, lead by the Ottawa Journal which published a number of controversial articles attacking Lt-General Guy Simonds, Chief of the General Staff. It was Simonds who conceived the idea of a Guards regiment and who was its major champion.

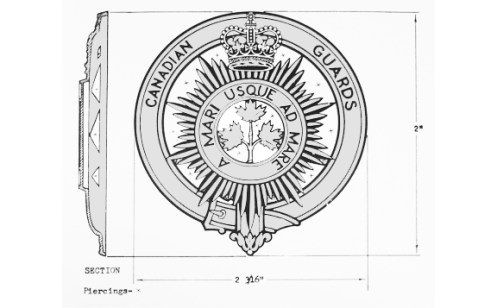

Cap badge of the Regiment of Canadian Guards. The Queen was instrumental in the design of this badge.

The regiment consisted of four battalions and a depot. The battalions were previously the 3rd Bn, The Royal Canadian Regiment (1st Bn Cdn Gds), 3rd Bn, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2nd Bn Cdn Gds), 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion (3rd Bn Cdn Gds), and 2nd Canadian Infantry Battalion (4th Bn Cdn Gds). These latter battalions were created for the 27th Canadian Infantry Brigade and were themselves created from a number of Militia regiments for service in Germany. The composition of the Cdn Gds was truly national and, unlike other Infantry regiments which were limited to specific territories, were allowed to recruit across Canada.

In keeping with the regimental establishments of the day, five ‘bands’ were authorized; a military band for the Regiment, fife and drum bands for the 1st and 3rd battalions, and pipe bands for the 2nd and 4th battalions. Following the stated desire of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, the Cdn Gds were to follow closely the uniform worn by the (UK) Brigade of Guards. In keeping with this principle the Minister of National Defence requested, through the Governor-General, permission from the Palace for the pipers to adopt the Highland uniform as worn by the Scots Guards, including the Sovereign’s Royal Stuart tartan.

If Her Majesty grants permission for the adoption of this distinctive Highland dress, which includes the Sovereign’s personal tartan, by the pipers of the Canadian Guards, this high honour will be a source of pride to the Regiment and will greatly enhance its prestige.

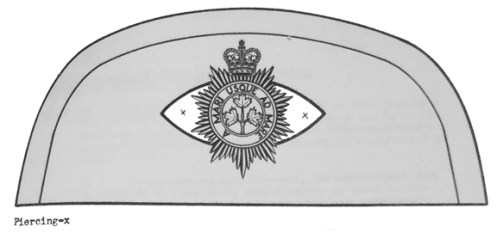

Permission to adopt the uniform, including the Royal Stuart tartan, was given in December 1954. At the same time, the Queen approved a drawing of the bonnet badge to be worn by pipers on the feather bonnet, at the base of the red and white feather plume. This badge, drawn in April 1954, featured the Cdn Gds cap badge in a white metal buckled belt (annulus) upon which was the regiment’s name. The dimensions were two inches high (to the tip of the buckle) and 2 3/16 inches wide.

An undated photo of a piper. His sporran cantle displays a badge as does his buckle while the remainder of his accoutrements are plain.

In addition to the uniform and bonnet badge, a number of other ancillary items were required in order to complete the uniform for pipers. These included kilt pins, plaid brooch, belt buckle, sporran badges, and cross-belt fittings. Wasting little time, by December 1955 Army Headquarters (AHQ) had drawings prepared for all of these items and submitted them to the Cdn Gds so that the regiment could obtain samples. These were to be provided at no expense to the public or from the grant provided for bands.

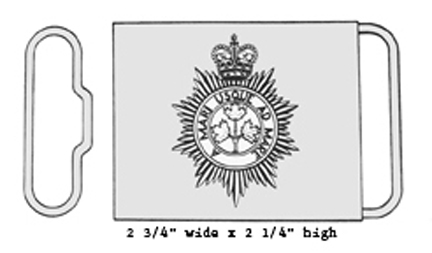

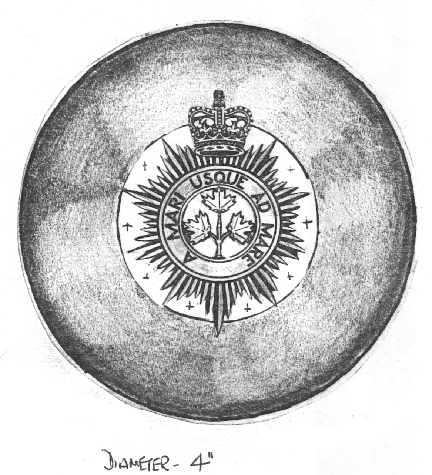

Proposed belt buckle. The size was fond too mall to properly cover the gap between the doublet and the kilt and was made larger in 1959.

What action was actually taken by the regiment and if the items they obtained were even close to the suggested pattern is unknown although, in 1959 the regiment proposed changes to some designs, specifically; that the bonnet badge be re-sized to 2 1/2 inches in diameter (exclusive of the buckle tip), the pipers buckle be made four inches wide and three inches high, and the buckle tip for the cross-belt be semi-circular instead of circular.

Although the first pattern badge (left) was that approved by the Queen, the second pattern (right) was more in keeping with the actual regimental badge. Courtesy Bruce Graham

While the AHQ supplied drawings show a very plain plaid brooch at least one firm proposed a regimental pattern. In late 1959 the London firm of Henry Potter, supplier of drums to the regiment, provided a drawing of a four-inch piper’s plaid brooch with the regimental badge centered. However, there is no evidence that these were ever purchased.

Brooch pin design proposed by Henry Potter Ltd., of London, the firm that supplied instruments to the bands, including the emblazoned regimental drums. The design does not appear to have been adopted.

Some of the changes were straight forward and approval from AHQ was routine provided some basic design criteria were met and procurement policy respected. However, changing the bonnet badge was problematic as the design was specifically approved by Her Majesty. The regiment was advised that the size could be altered but only if the entire badge were re-sized proportionally. In other words, the buckle could not be made larger while retaining the same size badge. The regiment agreed to this condition.

In spite of the drawings supplied to the regiment photographic evidence suggests that they obtained buckles and cross-belt fittings that were of more elaborate design and, for junior ranks, plain (no badge) belt buckles although photographs dating from the mid-1960s show the larger belt buckle embellished with the regimental badge.

Pipes and Drums of the 2nd Battalion, The Regiment of Canadian Guards, May 1965, at Camp Petawawa. Here, the large buckles exhibit the regimental badge.

As is customary in Highland dress, the regiment obtained both hair sporrans for full dress and leather sporrans for wear with battle dress. Most photographs of the former lack the badge on the cantle although it is shown worn on the leather sporran along with four leather tassels – emulating the four black ‘tails’ worn over the white hair sporran.

Army Headquarters drawing of the suggested cantle. The whole item, as with other badges and distinctions, were to be of polished white metal.

Note the badged leather sporrans which also include four leather tassels. The waist belt buckles are unadorned.

Another key item of dress for the bands was the Baldric (var. Baldrick) – the highly decorated sash worn by Drum-Majors. A standard design used by all Line Infantry regiments, with insignia specific to the Cdn Gds, was adopted. Each of the four battalions’ Baldric was identical with the sole exception of the battalion numeral. For the Cdn Gds depot, a lyre was substituted for this numeral.

Left, Baldric of the 1st Battalion (DND photo)

Right, Baldric of the Regimental Depot (author’s collection)

The author wishes to acknowledge valuable documents provided by Ken Joyce and Dr. James Boulton. Regrettably, requests for information to the Canadian Guards Museum at Garrison Petawawa remain unanswered.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars, below. You may also leave comments.

by Dan Mowat

Military pioneers were defined by Major Charles James of the Royal Artillery Drivers, in a book entitled ‘An Universal Military Dictionary[1]‘, published in 1821, as:

“PIONEERS, (pioniers, Fr.) in war-time, are such as are commanded in from the country, to march with an army, for mending the ways, for working on entrenchments and fortifications, and for making mines and approaches: the soldiers are likewise employed in all these things. Most of the foreign regiments of artillery have half a company of pioneers, well instructed in that important branch of duty. Our regiments of infantry and cavalry have 3 or 4 pioneers each, provided with aprons, hatchets, saws, spades, and pick-axes …”

and of their position in a military force, he writes:

“A detachment of pioneers, with tools, must always march at the head of the artillery, and of each column of equipage or baggage.[2]“

Records show that the role of military pioneers was established in the early 17th century, and perhaps earlier. They were originally attached to the artillery branch, but under the direction of the engineers, and they were responsible for creating the means to move and place field cannons in active warfare. Their role was to create roads, probably better described as tracks, and to open up areas near to the fighting so that the teams of horse drawn cannon could quickly get into position to support the infantry. Infantry could move quickly, at the whim of officers far behind the action, and the artillery had to keep pace or risk catastrophic results for the foot soldiers. In addition to road building, they were also responsible for the establishment and repair of offensive and defensive battlements and fortifications, entrenchments for men and munitions to have cover and shelter, secure areas for teams of service animals such as horses and mules, and perhaps most importantly, they provided carrying parties to get food and equipment to the forward area and to get the wounded back to the rear. Much of this work was done in front of or alongside the advancing infantry and artillery. These men were invariably in harm’s way.

Initially men assigned as pioneers were of the lowest class of the military force, and were not considered to be effective fighting forces. Major James refers to the degradation of officers and non-commissioned officers as punishment, being reduced in rank to that of private soldiers, and for private soldiers who misbehave, as follows:

“… So late as the reign of Charles I. private soldiers, for misbehaviour in action, were degraded to pioneers.[3]“

In his definition of Effective Forces, James makes the following distinction:

“Effective Forces. All the efficient parts of an army that may be brought into action are called effective, and generally consist of artillery, cavalry, and infantry, with their necessary appendages, such as hospital staff, wagon-train, artificers and pioneers: the latter, though they cannot be considered as effective fighting men, constitute so far a part of effective forces, that no army could maintain the field without them.[4]“

The make-up of the pioneers evolved over the following decades such that they became hard-working and intelligent men, coming under the military structure of the Engineers branch of service, and in addition to the traditional activities of pioneers, they undertook more engineering functions such as bridge building, setting of foundations upon which they erected buildings, and undertook civil construction works such as diversion of watercourses to get water nearer the fighting troops, and the drainage or mitigation of boggy areas.

When the Great War started in August 1914 Canada’s permanent military force was small, made up of a small number of infantry, cavalry, artillery and engineers. Canada had no navy at the time war broke out, and relied on the British Navy for protection on the high seas.Canada did, however, have a relatively large militia, having many seasoned soldiers who had fought as British forces in prior conflicts. However, many militia regiments in Canada were more social than military in nature, and although they had training in marching and other drill exercises, and musketry, they were not trained in military tactics. Each infantry battalion had a small number (usually 3 or 4) of trained pioneers, but there were insufficient numbers of pioneers to do any substantial work.

When the Canadians first arrived in France, there were no battalions of pioneers, and the work that would normally be done by them fell to the infantry. Not only were the fighting men required to attack and defend, they were also required to dig trenches, shore up battlements, carry food, munitions and equipment, dig latrines, build shelters and improve lodgings for themselves, and to assist the artillery in their movements. The infantry loathed this work, and they often cursed the engineers and pioneers for not being there when they were needed, and too often in insufficient numbers to relieve the infantry of this labour. In truth, this situation plagued the infantry right up to the summer of 1918, when General Currie reorganized the engineering branch and created several new battalions of engineers to undertake this work. After the war, Currie wrote in a letter to newspaper reporter Owen McGillicuddy:

“I am of the opinion that much of the success of the Canadian Corps in the final 100 days was due to the fact that they had sufficient engineers to do the engineering work and that in those closing battles we did not employ the infantry in that kind of work. We trained the infantry for fighting and used them only for fighting.”

The Canadian Pioneer Battalions were not raised until 1915, and even then, three infantry battalions that had been raised and trained in Canada, arrived in England and completed their training as infantry battalions, were converted to Pioneer Battalions shortly before mobilizing to France: the 48th Infantry Battalion became the 3rd Pioneer Battalion; and the 124th Infantry Battalion became the 124th Pioneer Battalion. The 123rd Infantry Battalion, Royal Grenadiers, was also re-purposed as the 123rd Pioneer Battalion, Royal Grenadiers. The 123rd had the special distinction of having the name of its home Regiment officially included in the name of the Battalion, with the blessing of the King. A book is currently being written about the history of the 123rd.

Badges of the 1st to 6th Pioneer Battalions, CEF. Courtesy http://www.britishbadgeforum.com/

The men of the 3rd, 123rd and 124th were uniquely skilled, in that they were first fully trained as infantry soldiers, and then added the skills of pioneers and engineers to their strong foundation as fighting men. Understanding infantry tactics while performing pioneer duties no doubt reduced the number of casualties suffered by the pioneers.

Badges of the 123rd and 124th Batalions which were converted to Pioneer battalions. Courtesy http://www.britishbadgeforum.com

The Canadian Pioneers of the Great War served valiantly, some of whom were decorated for their bravery and conspicuous gallantry in the face of the enemy. Their officers were respected by the men who served under them, which often was not the case in infantry battalions, where the men were contemptuous of their officers. The Commanding Officer of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (P.P.C.L.I.) became particularly fond of the men of the 123rd Pioneer Battalion, Royal Grenadiers for the services they rendered to the P.P.C.L.I. on battle fronts such as Passchendaele and Ypres.

[1] An Universal Military Dictionary, 4th Ed. Egerton, London, 1816, pg. 636

[2]An Universal Military Dictionary, 4th Ed. Egerton, London, 1816, pg. 29

[3] An Universal Military Dictionary, 4th Ed. Egerton, London, 1816, pg. 156

[4]An Universal Military Dictionary, 4th Ed. Egerton, London, 1816, pg. 240

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Mark W. Tonner

The Canadian Armoured Corps was formed, as a new branch of the ‘Active Militia of Canada,’1 effective 13 August 1940. Canadian units converted to armoured regiments, in this new branch, were organized under the then current British war establishment for an armoured regiment, which called for the regiment to be organized, and consist of:

a Regimental headquarters, of five officers and 12 other ranks, equipped with four cruiser tanks

a Headquarters squadron, of five officers and 120 other ranks, within:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with ten scout cars

- – an administrative troop

three squadrons:

- – each of seven officers and 138 other ranks, within a squadron headquarters and four troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with two cruiser tanks, and two close support tanks

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

for a total regimental strength of 31 officers and 546 other ranks, equipped with 46 cruiser tanks, six close support tanks, and ten scout cars.

Due to a lack of equipment and production delays, an amendment of 18 November 1940, stated that the scout cars, may vary in type, and that the tanks of an armoured regiment, may consist of a combination of various types of tanks.

The British war establishment for an armoured regiment, was replaced by a new Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, effective 30 September 1941. Under this Canadian war establishment, the basic allotment of scout cars and tanks remained the same, but there was an increase of two other ranks in regimental strength, bringing the total for an armoured regiment, to 548 other ranks. Also, under this new war establishment, provision was made for the attachment to an armoured regiment, of a paymaster (Royal Canadian Army Pay Corps), a medical officer (Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps), and two Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps armourers (for the maintenance and repair of weapons). Effective 1 April 1942, Canadian armoured regiments, that were equipped with five-man crewed tanks,2 were allowed an increase of 55 other ranks, to their overall regimental strength.

This new Canadian war establishment, was the war establishment, under which the six armoured regiments of the 1st Canadian Armoured Division (later renamed the 5th Canadian Armoured Division), were organized under, upon the formation of the division, effective 27 February 1941. The six armoured regiments of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, were also organized under this war establishment, upon the conversion and renaming of the 4th Canadian Division, to that of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, effective 26 January 1942.

By the end of 1942, the Canadian Army Overseas,3 due to the effects of manpower restrictions, and a serious shortage of shipping, from Canada, decided to completely reorganize based on British war establishments, in order to facilitate co-operation between formations and units of the British Army, and First Canadian Army.4 This reorganization of the Canadian Army Overseas, came into effect on 11 January 1943. As part of this reorganization, and to conform more closely to the British war establishment for an armoured regiment, a new Canadian war establishment, to replace that of 30 September 1941, was authorized, effective 1 January 1943. Under this war establishment, a Canadian armoured regiment was organized, and consisted of:

a Regimental headquarters

- – equipped with one command tank, and 11 cruiser tanks (eight of which were to be anti-aircraft tanks, if available)

a Headquarters squadron, with:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – a reconnaissance troop, equipped with ten universal carriers

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with nine scout cars

- – an administrative troop

three squadrons:

- – each of a squadron headquarters and five troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with four cruiser tanks

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

for a total regimental strength of 37 officers and 646 other ranks, equipped with 68 cruiser tanks, one command tank, ten universal carriers, and nine scout cars.

In addition, this new war establishment, allowed for an increase in regimental strength, of 64 other ranks, for those armoured regiments equipped with five-man crewed tanks, and an increase of 125 other ranks, for those equipped with six-man crewed tanks,6 and an increase of 189 other ranks, for those equipped with seven-man crewed tanks.7 The six armoured regiments of the reorganized 4th and 5th Canadian Armoured Brigades,8 in the United Kingdom, adopted this new war establishment, effective 31 January 1943.

Effective 8 May 1943, one recovery tank9 with three tradesmen, was allotted, to each squadron headquarters of an armoured regiment, and the strength of regimental headquarters, was increased by eight other ranks. Later in the month, a new war establishment was issued, effective 29 May 1943, which replaced that of 1 January 1943. This new war establishment, provided for a total strength of 37 officers and 727 other ranks, per armoured regiment. It also allowed for an increase in regimental strength, of 125 other ranks, for those armoured regiments equipped with six-man crewed tanks, and an increase of 189 other ranks, for those equipped with seven-man crewed tanks. Under this war establishment, a Canadian armoured regiment was organized, and consisted of:

a Regimental headquarters

- – equipped with one command tank, and 11 cruiser tanks (eight of which were to be anti-aircraft tanks, if available)

a Headquarters squadron, with:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – a reconnaissance troop, equipped with ten universal carriers

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with nine scout cars

- – an administrative troop

three squadrons:

- – each of a squadron headquarters and five troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with four cruiser tanks, and one recovery tank

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

for a total regimental strength of 37 officers and 727 other ranks, equipped with 68 cruiser tanks, one command tank, three recovery tanks, ten universal carriers, and nine scout cars.

This war establishment, stayed in effect, until it was replaced by a new Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, effective 12 January 1944. Under this war establishment, a Canadian armoured regiment was organized, and consisted of:

a Regimental headquarters

- – equipped with four cruiser tanks

a Headquarters squadron, with:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – a reconnaissance troop, equipped with 11 light tanks

- – an anti-aircraft troop, equipped with six anti-aircraft tanks

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with nine scout cars

- – an administrative troop

three squadrons:

- – each of a squadron headquarters, an administrative troop, and five troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with four cruiser tanks, and one recovery tank

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

for a total regimental strength of 38 officers and 657 other ranks, equipped with 61 cruiser tanks, 11 light tanks, three recovery tanks, six anti-aircraft tanks, and nine scout cars.

By this time, as the ‘Sherman’ tank10 with a crew of five, had become the standard cruiser tank used by a Canadian armoured regiment, the increases to regimental strength, for six-man, and seven-man, crewed tanks, was removed. The three armoured regiments of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent), who were at this time, in Italy, where they were organized on a special British war establishment for an armoured regiment, Middle East, did not adopt this new Canadian war establishment, until April 1944. Based on the special British war establishment for an armoured regiment, Middle East, the three armoured regiments of the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent), in Italy, were organized, and consisted of:

a Regimental headquarters

- – equipped with four cruiser tanks, and one anti-aircraft tank

a Headquarters squadron, with:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – a reconnaissance troop, equipped with six scout cars, and ten universal carriers

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with eight scout cars

- – an administrative troop

three squadrons:

- – each of a squadron headquarters, an administrative troop, and five troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with three cruiser tanks, and one anti-aircraft tank

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

Due to the favourable air situation which developed in both Italy and North-West Europe, later in 1944, the anti-aircraft troop with its six anti-aircraft tanks was deleted, and provision was made for the addition of seven tracked armoured vehicles, per armoured regiment, for the carriage of ammunition to replenish tanks in forward areas during ‘active’ battle conditions, effective 15 October 1944.

A new Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, which replaced that of 12 January 1944, was authorized effective 30 November 1944, and was the war establishment under which Canadian armoured regiments were organized, through to the end of hostilities, in North-West Europe, in May 1945. Under this war establishment, a Canadian armoured regiment was organized, and consisted of:

a Regimental headquarters, of five officers and 16 other ranks, equipped with four cruiser tanks

a Headquarters squadron, of nine officers and 172 other ranks, within:

- – a squadron headquarters

- – a reconnaissance troop, equipped with 11 light tanks

- – an intercommunication troop, equipped with nine scout cars

- – an administrative troop, equipped with one tracked armoured ammunition carrier

three squadrons:

- – each of eight officers and 153 other ranks, within a squadron headquarters, an administrative troop, and five troops

- – each squadron headquarters was equipped with four cruiser tanks, two tracked armoured ammunition carriers, and one recovery tank

- – each troop was equipped with three cruiser tanks

for a total regimental strength of 38 officers and 647 other ranks, equipped with 61 cruiser tanks, 11 light tanks, seven tracked armoured ammunition carriers, three recovery tanks, and nine scout cars.

A note on squadron organization within armoured regiments

In some Canadian armoured regiments, the three squadrons were each organized as consisting of a squadron headquarters, equipped with three cruiser tanks (instead of four), and four troops (instead of five), each equipped with four cruiser tanks (instead of three), which still gave the squadron a total of 19 cruiser tanks each.

Adoption of the Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, by armoured reconnaissance regiments

The creation of an armoured reconnaissance regiment, for each Canadian armoured division, had been part of the reorganization of the Canadian Army Overseas, in early 1943. Both regiments, upon conversion from that of ‘an armoured regiment,’ to that of ‘an armoured reconnaissance regiment,’11 were organized under the newly created and authorized Canadian war establishment for an armoured reconnaissance regiment. This was subsequently replaced, by a new war establishment, effective 14 May 1943, which in turn, was replaced by another new war establishment, for an armoured reconnaissance regiment effective 12 January 1944. In March 1944, so that an armoured division could at any time split into two brigade groups, each of two armoured regiments, and two infantry battalions, General B.L. Montgomery, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, 21st Army Group,12 directed that all the armoured reconnaissance regiments, within 21st Army Group, adopt the war establishment of an armoured regiment, effective 13 March 1944.

As such, the 29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, reorganized under the then, current Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, and subsequently, that of 30 November 1944. The 3rd Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The Governor General’s Horse Guards), of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division, who at this time (March 1944), were in Italy, remained organized, under the Canadian war establishment for an armoured reconnaissance regiment, of 12 January 1944, until they moved to North-West Europe, in March 1945, at which time, they to, reorganized under the then, current Canadian war establishment for an armoured regiment, as per the 21st Army Group policy, of armoured reconnaissance regiments, adopting the war establishment of an armoured regiment.

Sources:

– Army Headquarters Report No. 57, A Summary of Major Changes in Army Organization, 1939-1945, dated 22 December 1952, complied by Major R.B. Oglesby, Historical Section (General Staff), Army Headquarters, Ottawa, Ontario.

– General Orders 1940, as issued to the Canadian Militia/Army by order of the Minister of National Defence.

– Part “A,” General Orders 1941, as issued to the Canadian Army by order of the Minister of National Defence.

– Part “A,” and Part “B,” General Orders 1942, as issued to the Canadian Army by order of the Minister of National Defence.