by Roger V. Lucy

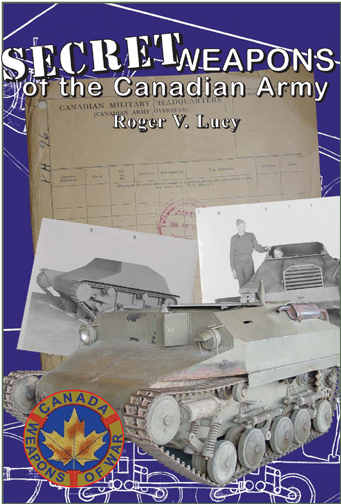

In North-West Europe in November 1944, the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) was seeking a means to deliver more high-explosive firepower, than could be provided by their Staghound armoured cars’ 37mm guns. The Dragoons were often too far out ahead to call in artillery support, but needed an “on-call” HE capability to soften up resistance. This was supposed to be supplied by the Staghound III, with a 75mm gun, but it had yet to enter production, Efforts to obtain some M7 Priest 105mm self-propelled guns were also unsuccessful. With the permission of HQ First Canadian Army, the Manitoba Dragoons borrowed four obsolete Rocket Launcher Rails Mk.I and a number of 60 lb. warhead aircraft rockets, used with the Hawker Typhoon from the RCAF.

The modifications were a carried out on 19 November, 1944, by 40 LAD. The rails were attached to the mantlet so the rockets could be elevated with the gun (no doubt with some difficulty, given the rig’s extra 200 or so extra kilos). Rotating the turret provided the traverse. The edges of the rails protruded about 3 inches (7.5 cm) beyond the sides of the armoured car.

![Photographs from First Canadian Army’s Weapons Technical Staff Officer Major Sangster’s report showing the rails fitted to a XII Manitoba Dragoons Staghound.The vehicle bares the tac sign of the HQ Company]](https://milart.blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/xii-dragoons-staghound-rl-11-44a1.jpg?w=497&h=317)

Photographs from First Canadian Army’s Weapons Technical Staff Officer Major Sangster’s report showing the rails fitted to a XII Manitoba Dragoons Staghound.The vehicle bares the tac sign of the HQ Company]

The system was tested on 20 November and more formal trials were held at St. Phillip’s Island – under the supervision of First Canadian Army AFV staff – on 26 November and 2 December. Results were generally promising, although – due to limitations of the ground – the ranges achieved could not be accurately measured. It was estimated that rockets went anywhere from 100 to 3,000 yards (90 to 2,750 metres). Accuracy (particularly in terms of range) was wanting, and at short ranges the rocket warheads often failed to detonate. Neither the car nor its crew suffered as a result of the rockets’ back-blast and the trials were considered sufficiently successful for First Canadian Army to recommend to CMHQ that further development be undertaken.

The rocket Staghound being readied for its test firing in early December 1944. MilArt photo archives

In the meantime 12th Manitoba Dragoons continued to work their original design. In February 1945, 40 LAD was preparing to fit rocket rails to other Staghounds to support patrols across the Waal river, but this was cancelled when the regiment was ordered into a mobile offensive role.

After the 12th Manitoba Dragoons CO, Lt-Colonel Roberts, was given command of 8 Canadian Infantry Brigade, he considered mounting rockets on the sides of a Universal Carrier, but nothing seems to have come of this. However, another formation, 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade conducted a similar experiment, fitting two pairs Typhoon launcher rails to the sides of one of their half-tracks. The rails were pivoted to allow range adjustment and a sheet metal guard was fitted over the top of the vehicle to protect the crew from the rockets’ back-blast. Ranges of up to 1,500 yards (1,350 metres) were attained, but accuracy was erratic. First Canadian Army’s Weapons Technical Staff Officer Major A.G. Sangster, concluded that, given the ballistic unsuitability of these rockets for a ground role, it had “worked as well as expected.” Sangster believed the idea seemed to have potential and he recommended the development of a prototype more suited to a ground role. In essence, this was same conclusion reached following the Staghound trials, but in this case there was no follow-up to Canada’s own “Stuka (or rather Typhoon) zu Fuß (21cm rockets mounted on the sides of the SdKfz.251 half-track).”

Photographs of 4 CAB’s half-track mounted rocket launcher from First Canadian Army’s Weapons Technical Staff Officer Major A.G. Sangster.s report.

The British Coldstream Guards also undertook similar experiments in early 1945 fitting Typhoon rocket launcher rails to the sides of a Sherman Firefly. Christened the Tulip, it reportedly had the good luck to hit, and kill, a Tiger.

While this ended field expedient rocket launchers Canadian Military Headquarters (CMHQ) in London took up the proposal, and in January 1945 conducted their own tests, using a similar arrangement. While the results were promising, the performance of the Mk.I rails was deemed unsatisfactory. British experts pointed out that air-launched rockets were unsuitable for ground use, and recommended that further development focus on SEAC spiral launchers, using 3-inch (76mm) and 5-inch (125mm) rockets – types already allocated to First Canadian Army for the Land Mattress. The War Office saw no requirement for rocket-armed armoured cars, but was interested in developing cast aluminum spiral launchers that could be mounted on any armoured vehicle. Staff at CMHQ, took the idea further, drawing up a concept for a dedicated vehicle, with the turret replaced by the launcher tubes and an observation cupola for the operator. Work was therefore continued, as a long-term development, still using the Staghound as the platform.

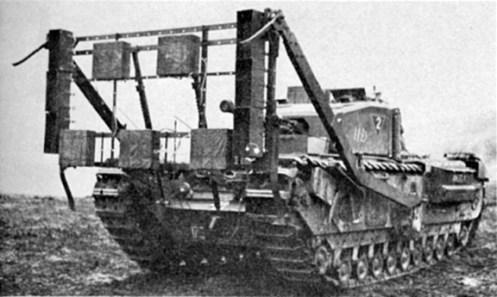

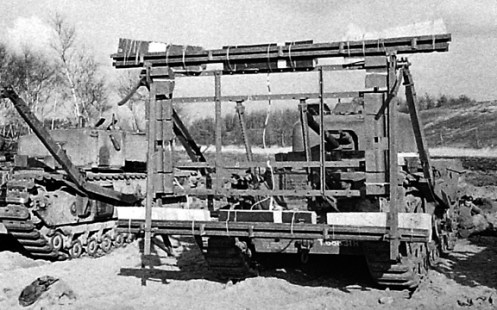

With help from British rocket experts at CEAD, a launcher using six cast aluminum spiral launching rails was developed. CMHQ ordered 12 pilot cast-aluminum spiral launcher tubes from a Birmingham foundry – the Northern Aluminium Co. The results were unsatisfactory, only five tubes were delivered before the rest of the order was cancelled in July. In order to proceed with the trials, No.1 Canadian Base Workshops (1 CBW) fabricated a set of eight steel tubes. After looking at two possible mounting options 1 CBW mounted four on each side, in banks of two, attached to the turret by angle irons and steel tubing. The rails were linked (with a counter-weight) to the gun barrel, and elevated with it. A range dial (in the form of a quadrant, attached to the gun’s trunnions) allowed more refined aiming.

This photograph from the report on the trials of the Staghound Rocket launcher at Ynys-Las South Wales, in April 1945 shows details of the mechanical linkages of the Rocket Projector mounting.

Another view of the blast damage. The junction boxes for the electrical firing gear can be seen on the rear of the projector.

The revised system was ready on 5 April and tested on 26 April at Ynys-Las South Wales. Some 35 rockets were fired in all, with generally satisfactory results. While little harm was done to the crew, the back-blast of a full salvo damaged the rear mud-guards and activated the CO2 fire-extinguishers. In addition, ripple firing caused serious erosion to the launcher rails, eventually damaging one so much that the fin of one of the rockets was pulled off, causing it to break up in flight. The addition of blast deflectors to protect the CO2 release handles was recommended.

This series of photographs taken at Ynys-Las on 26 April 1945, shows the Staghound rocket launcher undertaking a shoot. The vehicle belongs to 1 CACRU. Note the damage to the fender from the blast. This photograph shows the intensity of the back-blast.

A new contract for cast aluminum tubes was awarded to High Duty Alloys Ltd. of Slough which was able to deliver. Getting range access delayed testing the redesigned launcher. It finally took place the British Chemical Warfare Establishment at Porton Down, in December 1945. The results were very successful; damage to the fins was avoided by champfering their edges. However – and not surprisingly, given Porton Down’s purpose – British interest in the system now concentrated on its potential for delivering chemical and smoke rounds. Work did continue of the project – to develop a suitable smoke round – at least into March 1946. Eventually the Staghound Rocket Launcher was returned to Canada.

Sources

Lucy, R,V., Secret Weapons of the Canadian Army, Service Publications, Ottawa, 2006

Library and Archives Canada RG 24 Series C‑3

Volume 9365, File 38/ARM VEH/32, T17 E1 armoured car

Volume 9376: 38/SD TECH RPTS

Volume 9378, file 38/WAR DIARY/1 WD DDEM [Directorate of Design, Equipment and Mechanization

Volume 9391 excised photographs for 55 series files

Volume 16288 WD No. 40 Light Aid Detachment, Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (attached to 18th Canadian Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons),

Reel C-5777, file 55/553/1/ AFV(W) First CA correspondence

Reel C-5779, file 55/733/T85

C-8279 Army – Reports from 21st Army Group – Armoured Fighting Vehicles

Reel T-12714 WD 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons) 1943/11-1945/01

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

For more information on the Stag rocket Launcher order “Secret Weapons of the Canadian Army” from Service Publications

by Mark W. Tonner

Introduction

After the Dieppe raid on 19 August 1942, and as a result of the high number of casualties suffered by members of Royal Canadian Engineers during the raid, a number of devices were devised whereby explosives could be carried up to sea walls and other fortifications, placed in position and detonated from a distance. All these devices involved some type of framework on the front of a Churchill tank,1 which was used to hold the explosives. As part of their development, on 18 February 1943, a composite Troop of six Churchill tanks of the 14th Canadian Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)),2 Canadian Armoured Corps (hereafter referred to as the Calgary Regiment), commanded by Lieutenant V.J. St. Martin, were sent to Witley, Surrey, for special training exercises in connection with anti-tank mines and methods of clearing minefields and tank obstacles. They were used in the trials of two of these experimental explosive devices, under the auspices of the Special Device Branch of the British Department of Tank Design.

A front view a Churchill Mark III tank, named ANGELA, of No. 2 Troop, “A” Squadron, The

Calgary Regiment, at Whitley, Surrey, fitted with the “Onion” explosive device. Note the pair

of hinged legs at the bottom and two fixed outward-facing legs at the top. Also, of note, is

the placement of the high explosive charges on the sides and face of the framework. Source:

authors’ collection.

A right-side view of ANGELA, showing the right-side arm, attached to a bracket which supported the vertical “Onion” explosive device framework on the tank’s front. Note also, the two outward facing legs, attached to either corner of the top of the framework. Source: authors’ collection.

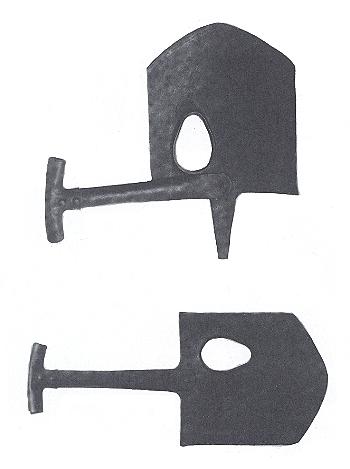

The “Onion” explosive device

The “Onion” was an explosive device designed to allow a Churchill tank to move explosive charges into place to breach or demolish obstacles. Arms attached to brackets on the sides of the tank supported a vertical framework with a pair of hinged legs at the bottom and two fixed outward-facing legs at the top. Six oblong 30-pound (14-kilograms) high explosive (HE) charges were attached, three to a side, to the outer face of the framework in boxes, or in a pattern on the outer face of the frame work, to suit the intended target. The frame was then driven into place and released, with the two hinged legs on the bottom of the frame meeting the ground first, forcing the frame to fall forward against the obstacle, while the tank reversed away, approximately 100-feet (30-metres), and trailing an electric ignition cable. Once the tank had reversed away a safe distance, the charges arranged on the framework were detonated. The frame could also be hung from obstacles, such as walls or bunkers, by using the two outward facing legs on either corner of the top of the framework.

The “Onion” worked well against obstacles such as “Dragon’s Teeth” (concrete tank traps) and steel beach obstacles, but was not always effective against walls or bunkers, because the frame did not always position itself correctly after being released, reducing the impact of the explosion. The “Onion” was deemed a failure and never entered production.

A left-side view of ANGELA, of No. 2 Troop, “A” Squadron, The Calgary Regiment, at Whitley, Surrey. The two poles sticking up to the right front of ANGELA are those of the “Churchill with

Bangalore Torpedoes” device, which is fitted to another Calgary Regiment tank. Source: MilArt photo archive.

Front view of a Churchill Mark IV tank, of The Calgary Regiment, at Whitley, Surrey, fitted with the “Onion” explosive device. In this case, the high explosive charges in boxes are attached three along the top and three along the bottom of the outer face of the framework. Note also, the two outward facing legs, attached to either corner of the top of the framework, which would enable the device to be hung from an obstacle such as a wall or bunker. Source: MilArt photo archive.

Churchill with Bangalore Torpedoes

Another project that involved the Calgary Regiment’s six tanks at Witley, was the trials carried out on a second explosive device based on the Onion framework. Two lengths of Bangalore Torpedo3 were fitted upright to the face of the “Onion” vertical framework. This was then dropped into light obstacles, such as barbed wire entanglements, which when detonated was supposed to clear a path through the obstacle. This explosive device was simply known as the “Churchill with Bangalore Torpedoes,” but as a result of poor performance during the trials, it was also considered a failure and never entered production.

Three (of six) Churchill tanks of The Calgary Regiment, at Whitley, Surrey. The “Churchill with Bangalore Torpedoes” is fitted to the furthest tank, while in the centre, a Churchill Mark IV tank, is fitted with the “Onion” explosive device. On the nearest tank, a Churchill Mark III tank, of No. 11 Troop, “C” Squadron, is the framework of the “Onion” explosive device, to which no explosives have been fitted. Note the outward-facing leg in the centre on the right side of the photo, which would be attached to the top right-hand corner of an “Onion” explosive device framework that is fitted to a tank that is not in the photo. Source: MilArt photo archive.

A Churchill Mark III tank of No. 11 Troop, “C” Squadron, The Calgary Regiment, at Whitley,

Surrey, fitted with two upright “Bangalore Torpedoes” to the face of the “Onion” vertical

framework. Source: authors’ collection.

Notes

- The British designed and built Infantry Tank, Mark IV, Churchill (A22).

- The 14th Canadian Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)), along with the 11th Canadian Army Tank Regiment (The Ontario Regiment (Tank)), and the 12th Canadian Army Tank Regiment (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), were the three ‘army tank regiments’ of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, all of which were equipped with the Churchill ‘infantry’ tank.

- A Bangalore Torpedo is made up of one or more connected metal tubes filled with explosives and equipped with a firing mechanism, especially for destroying barbed-wire entanglements, mine fields, etc., and consisted of 3-inch (8-centimetres) diameter pipe, issued in 20-foot lengths (6-metre).

Bibliography

Fletcher, David, The Universal Tank, British Armour in the Second World War, Part 2, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London, England, 1993.

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

RG24, National Defence, Series C-3, Volume 14243, Reel T-12708 – War Diary of the 14th Canadian Army Tank Regiment (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)), Canadian Armoured Corps, from 1 February to 28 February 1943, Volume 25

The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom

WO 165/132 – Appendix “U” – Experiments & Projects, of the Half Yearly Report on the Progress of the Royal Armoured Corps, Report No. 6 – 31 July to 31 December 1942

Tonner, Mark W., The Churchill Tank and The Canadian Armoured Corps, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2011.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

To read the fascinating story of Canadian use of the Churchill tank order this book at http://www.servicepub.com

by Clive M. Law

MAYER, Paul Anthony, Major – Chevalier of the Order of Leopold II with Palm and Croix de Guerre 1940 with Palm – Infantry (The Algonquin Regiment) – awarded as per Canada Gazette dated 31 August 1946 and CARO/6733 dated 2 September 1946. (NOTE: Canada Gazette has Paul Anthony and the typed citation had Paul Anthony with Anthony crossed out and Augustus printed in.)

Recommended by Lieutenant-Colonel J.F.R. Akehurst, Commanding Officer, the Algonquin Regiment on 20 September 1945; approved by Brigadier H.P. Bell-Irving, Officer Commanding, 10 Canadian Infantry Brigade on 20 September 1945 and passed forward on 21 September 1945; approved by Major-General H.W. Foster, General Officer Commanding, 4 Canadian Armoured Division; approved by Lieutenant-General G.G. Simonds, General Officer Commanding, Canadian Forces in the Netherlands on 25 September 1945 and passed for action on 6 October 1945. The citation reads:

On 20 September 1944, [the] Algonquin Regiment was fighting in the area of Assende, south of the Belgium-Holland border. The enemy were holding the area north of this town in considerable strength with headquarters at Philipine, Holland. At 0830 hours, Major Mayer, Commander “D” Company, was ordered to try to outflank the defences to the east. Leading his Company personally he pushed up across the open country to Valk. So complete was the surprise achieved by this attack that they succeeded in capturing a rear echelon, including a complete pay staff. Establishing himself at this point, Major Mayer dug in and set up the defences but before consolidation was complete the company was subjected to a heavy barrage, followed by a counter-attack by self-propelled artillery and infantry. Exposing himself many times to enemy fire, he directed and encouraged his men so skilfully that they held their ground. The enemy was completely routed with 150 prisoners taken in the engagement. This action was one of many in the Belgian campaign during which Major Mayer distinguished himself by his bravery and sterling leadership and his exploits enjoy a very high reputation in his unit.1

This series of photographs are from the Canadian Army official photos of the Congo mission. Taken shortly after the action for which Mayer was awarded the George Medal he is shown with the helicopter pilot (top) and the R22eR Sergeant who accompanied him. The other photos show UN officers involved in the planning and the helicopter that transported the mission members. MilArt photo archives

Awarded George Medal as Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Augustus Mayer, MBE, CD as per London Gazette of 16 October 1964 and Canada Gazette of 03 October 1964 while serving with the Canadian Army in the Congo.

Awarded George Medal as Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Augustus Mayer, MBE, CD as per London Gazette of 16 October 1964 and Canada Gazette of 03 October 1964 while serving with the Canadian Army in the Congo.

At one point Lt Col Paul Augustus Mayer, MBE, GM, CD, served as Chief Instructor at the Guards Depot and Senior Major of the 1st Battalion.

THIRD SUPPLEMENT TO

The London Gazette

OF FRIDAY, 12th FEBRUARY, 1954

The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on the advice of Her Majesty’s Canadian Ministers, to give orders for the following promotion in, and appointments to, the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, in recognition of gallant and distinguished services in Korea:—-

To be Additional Officers of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order :— Major Paul Augustus MAYER, C.D. (ZB 2864), The Royal Canadian Infantry Corps.

SUPPLEMENT TO

The London Gazette of Tuesday, 1 3th October 1964

CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD

St. James’s Palace, London S.W.I.

16th October 1964.

The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on the advice of Her Majesty’s Canadian Ministers, to approve the award of the George Medal to the under-mentioned:

ZD 2864 Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Augustus MAYER, M.B.E., C.D., The Regiment of Canadian Guards.

On 24th January 1964 Lieutenant-Colonel Mayer was charged with the rescue operations of American and European Missionaries in Kwilu Province. On 27th January 1964 during a rescue operation at Kisandji this officer rescued two nuns and three priests. Eight nuns and one priest remained. He was requested by one of the priests to speak to the native chief in an endeavour to free the remainder of the Missionaries. During talks with the native chief council, Lieutenant-Colonel Mayer was hit on the back of the neck with a club and knocked unconscious. Members of the Jeunesse removed his revolver, beret and web belt. The council argued for killing him there and then. They informed him that if one shot was fired he and all the nuns would be killed. At this point, a frenzied Jeunesse thrust the pistol in his stomach and pulled the trigger. Fortunately there was no round in the chamber. In the meantime three priests and two nuns were able to board the helicopter. After arrangements had been made to free the remaining eight nuns, Lieutenant-Colonel Mayer was allowed to leave amongst a wild and screaming mob. During the whole operation, this officer’s life was in constant danger. His behaviour at all times was exemplary. His courage and composure was an inspiration to both the UN Personnel serving under him and also for the Missionaries. On several occasions he refused to leave his post until all Missionaries had been evacuated. He behaved at all times well above the call of duty and by his patience and energy in dealing with the members of the Jeunesse saved many lives.

More info cited in “Warrior Chiefs: Perspectives on Senior Canadian Military Leaders”, edited by Colonel Bernd Horn, Stephen Harris

Author,” I’ve Had Good Innings”, General House Publishing, Renfrew, ON, ISBN 1-89711336-6

OBITUARY

Paul A. MAYER

Born: 1916

Date of death : 2006-07-05

Wife : Pamela McDougall

MAYER, Paul A. Lt. Col. Retired, M.B.E., G.M., C.D. Peacefully at the Montfort Hospital on Wednesday, July 5, 2006 in his 90th year. Beloved husband of Pamela (nee McDougall). Loving grandfather of Crystal Mayer and David Mayer of Vancouver, B.C. He will be fondly remembered by his sister, niece and nephew, all of Melbourne, Australia. Friends may visit at the Central Chapel of Hulse, Playfair & McGarry, 315 McLeod Street on Monday, July 10, 2006 from 2 to 4 and 7 to 9 p.m. Funeral service will be held at St. Bartholomew’s Anglican Church, 125 MacKay Street, Ottawa, on Tuesday, July 11, 2006 at 11 a.m. As an expression of sympathy, memorial contributions to the C.N.I.B. or the V.O.N. would be appreciated. Published in the Ottawa Citizen from 7/8/2006 – 7/10/2006

Notes

1. From “Courage and Service” CD (Service Publications, Halliday and Blatherwick)

by Roger V. Lucy

In 1943, the War Office announced number of new small arms projects and asked Canada in which types it wished to participate. The Canadian crown corporation, Small Arms Ltd., (SAL) of Long Branch, Ontario (a neighbourhood of Toronto), responded with designs for a lightweight rifle, a machine carbine, and a self-loading rifle (SLR).

Lightweight Rifle

In August 1943, SAL was able to demonstrate its design of a lighter version of the No.4 rifle, to Major-General “Tubby” Lethbridge’s 220 Military Mission, which was touring North America looking into weapons and equipment for use in South-east Asia. The British required a lightened version of the .303 rifle, accurate out to 400 yards (360 metres). In light of this interest, DND’s Directorate for Small Arms and Vehicles (DVSA) undertook to have its further development funded by the Army Technical Development Board (ATDB).[1] Project 66 was approved on 15 December 1943. Two pilots were sent to the UK for trials, which took place at Bisley in early February 1944. The Canadian design lost out, and its British competitor was adopted as the No.5 (“Jungle Carbine”). Compared to the No.5, the British deemed the SAL rifle to be less accurate, had excessive muzzle flash, and required the manufacture of new components such as a new trigger group (which been redesigned by SAL as an improvement on the No.4) and shoulder pad. The pad was required to offset the extra recoil caused by the rifle’s lighter weight and shorter barrel – 6 3/4 lbs. (3 kg) and 22 inches (55 cm) respectively. The SAL rifle had a full length but lightened stock, held by two screws and accepted the No.4 spike bayonet.

SAL’s prototype for a lightweight version of the No.4 rifle. It lost out in competition to the British No. 5 Jungle Carbine. MilArt photo archives

Advised of an Indian requirement for 25,000 rifles, with specifications similar to its lightweight rifle, SAL undertook a redesign, incorporating some of the features of the British No.5. The prototype was completed in April 1944, but India adopted the No.5 rifle, which was now in production. Australia also trialed the first pattern Canadian lightweight rifle in August 1944. The Australians were impressed by the SAL rifle’s accuracy, handling and serviceability but deemed its excessive flash unacceptable. They also found it too light – particularly in the butt portion – for Australian methods of close-in fighting. In December 1944, SAL decided to halt further development. The lightweight rifle project was declared completed by the ATDB on 5 January, 1945.

Carbine, Machine, Canadian Experimental

When SAL had approached DVSA for funding for the development of a machine carbine, DVSA’s Director, Colonel J.L. McAvity advised SAL that, despite the stream of complaints from the field about the Sten, he could not get funding from the ATDB, unless the General Staff issued a requirement for a new machine carbine. SAL returned to the charge on 28 August, 1944 and McCavity obtained approval for the project at the ATDB’s September 5, 1944 meeting. This was based on a General Staff specification which called for a 9mm Parabellum, selective fire weapon with: satisfactory reliability in the most adverse conditions; weighing no more than 6 lbs. (2.7 kg) without a magazine; and capable, when firing single shots, to place five bullets in a 12 inch x 12 inch (30cm x 30cm) group at a range of 100 yards (90 metres). To improve accuracy, the cyclic rate was to be no more than 500 rpm. It was to have compact, short, 30-60 round magazines. To minimize stoppages, the magazine lips were to be incorporated in the body of the gun. The butt was to be removable, and the metal parts rust-proof. Finally – an aesthetic dig at the homely Sten – its appearance should inspire the user’s confidence.

The project got off to a slow start as SAL had been concentrating its development work on its self-loading, sniper and lightweight rifle designs. In December 1944, two of its designers George Kersey and Anton Rosciszewski, came up with an innovative “positive feed,” with the magazine mounted horizontally. A rocker arm worked by the bolt’s blow-back action, removed the round from the magazine, rotated it 90o, and chambered it. This arrangement protected the magazine and ammunition feed from dirt dust and sand – albeit at the expense, in early versions, of more misfeeds and ejection malfunctions. The trigger was based on a design Rosciszewski had developed for a modified Sten. Pressure on the top of the trigger fired the weapon in a fully automatic mode while pressure on the bottom of the trigger fired the weapon semi-automatically.

The Machine Carbine designed by Anton Rosciszewski of SAL, note the dual-action trigger which allowed selective fire. MilArt photo archives

The first pilot was completed in May 1945, and by the end of July it had successfully test fired 6,000 rounds. At that time a second prototype was under construction with modifications to bring it down to the specified 6 lbs. weight limit (loaded weight was in fact somewhat more than 7 lbs. – 3 kg), and the weapon had a fixed wooden stock, with a wooden fore-grip.

In October 1945 DND agreed to pay SAL $10,000 to build four more prototypes. Work continued after January 1946 when SAL was taken over by Canadian Arsenals Ltd, to become its Small Arms Division. In July 1946, the Inspection Board of the United Kingdom and Canada (IB) tested the experimental machine carbine against the Stens Mk. II and Mk. V. The experimental machine carbine had a lower cyclical rate of fire (492 rpm, against 610 and 534 respectively), and was more accurate, more tolerant of mud, somewhat less inclined to fire spontaneously when dropped, and was judged easier to carry and operate. However, it did have a notably higher rate of misfeeds. The project was sufficiently promising to be designated a long term one when the ATDB was disbanded at the end of 1946. In September 1948, it was trialed by the British Board of Ordnance against two experimental British designs, the EM2 and EM6. It performed very well (especially once the British solved its feed problems), but was deemed too long and heavy, lacked the folding butt of the EM2 and EM6 and, above all, was too expensive. Trials continued in Canada, it was tested in winter conditions at Churchill in the winter of 1948/49, but in the end the Canadian machine carbine, like the EM2 and EM6 lost out to the British Sterling submachine gun.

Self-loading rifles

As far back as September 1940, DND had monitored US developments of self-loading rifles , not only of the M1 Garand but also a Winchester project to develop an upscaled version of its M1 carbine, firing a standard full size cartridge (ATDB Project 18). While this passed Winchester’s own tests, it failed dismally when trialed at Aberdeen Proving Grounds in January 1943.

The 30 calibre Winchester Carbine being test fired. Note the addition of a bipod. MilArt photo archives

Based on a misapprehension of what the US M1 carbine actually was, the ATDB, at Lt.General McNaughton’s request, initiated Project 27 on 16 October, 1942 to investigate whether it could be developed as a Light or even Medium Machine gun. While it soon realized the error of its ways, 500 M1 carbines, and 150,000 rounds were obtained, and issued for trials by 4th Canadian Armoured Division in May and June 1943. They were issued to 4 Anti-tank Regiment, 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade Workshop and Divisional HQ, as a substitute for both pistols, for those issued side arms, and for other troops’ rifle. The former found it superior to their pistols in terms of range and accuracy; the latter found it more compact and easier to carry in confined spaces than the Lee Enfield. The only criticism was that it had far less stopping power than the Thompson SMG. In the end the M1 carbine was rejected because Lt.General McNaughton saw no requirement for it, and did not want to introduce a new type of ammunition into the supply chain.

No further work was done on SLR development in Canada until late in the War. DND’s views were largely guided by the initial British General Staff belief that semi-automatic rifles were of little utility, given the great increase in the number of machine guns that were being issued. Nonetheless, in April 1944 SAL initiated its own development- as a private venture – in response to a 1943 British specification for a gas-operated SLR with a rotating bolt and using a rimless 7.92 mm round. Design work began in November 1943, with the first pilot being ready for trials in June 1944. It used a dropping bolt locking mechanism similar to the Bren. To work properly this required very heavy parts and the design was declared obsolescent in January 1945. Its redesign was begun in March 1945 and test shot in May.

The SAL 7.92mm rifle was 45 inches long (115 cm), with two-piece wood furniture, a blade foresight with wind guard and peep type back sights, and a flash eliminator. It had a 10 round charger-fed magazine but could take a 20 round box magazine. It took the No.5 bayonet. Muzzle velocity was 2,500 f/s (750 m/s). MilArt photo archives

The revised SLR had a forward locking bolt, and while considerably lighter was deemed too complex and delicate. A more robust version was developed with a threaded sleeve and – to give a more positive firing mechanism – hammer firing. This version was test-fired in August 1945. By December, the EX1, as it came to be designated, had successfully fired 800 rounds, and DND became seriously interested in the weapon – particularly as British efforts at designing a 7.92mm SLR were meeting with little success – tending to jam when firing British made ammunition.

The EX1 before work was switched to a design based on the .30 calibre T65 round. MilArt photo archives

The Director of Artillery recommended that further development be funded. SAL set about refining the design to reduce its loaded weight from 10 lbs. to 9 lbs. (from 4.5 to 4 kg), and to simplify manufacture, assembly and stripping the weapon. SAL expected to begin work on the pilot in January 1946 and have it ready by April. Soon thereafter the British changed their requirement to conform to the US T65 .30-06 round. While Small Arms Ltd had, by then, been wound up, the ATDB agreed, in July 1946, to fund work at Canadian Arsenals on a revised design, the EX2, which would not only accommodate the T65 round but further reduce weight – the goal being 7 lbs. (3.2 kg). The possibility of selective fire was also to be examined. Work on this weapon continued into 1950 – eventually, of course, it was the FN, firing 7.62 NATO that was selected.

Canadian Arsenals Ltd. EX2 prototype automatic rifle, chambered to the US T65 .30-06 round. MilArt photo archives

Notes

[1] For more information on the role of the ATDB in funding the development of new equipment see Secret Weapons of the Canadian Army, Service Publications 2006.

Bibliography

Lucy, R,V., Secret Weapons of the Canadian Army, Service Publications, Ottawa, 2006

Directorate of History and Heritage (DHH)

115.41013 (D17) Project 18 Self‑loading rifle

115.41013 (D65) Project 66 Lightened Rifle

Library and Archives Canada RG 24 Series C‑3

Reel C‑8386 file 8928‑11‑18 , Army Technical Development Board ‑ Project No. 18 ‑ Self‑loading rifle

Reel C‑8388, file 8928‑11‑66 Army Technical Development Board ‑ Project No. 66 ‑ Lightened rifles

Reel C‑8389, file 8928‑11‑907 ‑ Army Technical Development Board ‑ Project No. 907 ‑ Improved machine carbine

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Roger V. Lucy

A major threat to allied armour was the German Panzerfaust. Contrary to popular opinion the Panzerfaust (the name means armoured fist) was not a rocket-propelled grenade launcher, but disposable, one-man recoilless weapon. It used a black powder charge to discharge a large over-calibre fin-stabilized, hollow-charge warhead from a cast iron launching tube. The recoil from the discharge was counteracted by a three metre (10 foot) long jet of flame, vented out the back of the launcher. Introduced into service in mid-1943, as the Panzerfaust (Klein) or Gretchen, it was steadily improved. The Panzerfaust 30 (with an optimum range of 30 metres) had a larger warhead and longer launching tube. Subsequent versions, the Panzerfaust 60 and Panzerfaust 100 saw the optimum range increase to 60 and then 100 metres respectively. A re-loadable 150 metre version was going into production at the War’s end, but few if any, ever reached the front.) Overall, the Panzerfaust was a little over 1 metre (40 inches) long and weighed 6.8 kg (15 lb). By April 1944 Panzerfaust production had reached 200,000 per month, and 1.5 million per month by December. By May 1945, some 7 million had been delivered to the German armed forces and to para-military organizations such as the Volksturm and Hitler Jugend.[i]

An inert Panzerfaust 60 in the author`s collection, showing the complete round, and the actual fin-stabilized war-head

While relatively simple to use, and requiring little training, the Panzerfaust was not a weapon for the faint-heated. The fusing and its cylonite explosive (a TNT/RDX mixture) could be fickle. The range was short, and its rudimentary sighting arrangements made accuracy poor. The back-blast restricted where it could be used and betrayed the user (operational research indicated that users had a about 50% chance of surviving their attack on a tank). That said, if it struck a tank squarely, the Panzerfaust’s 14 cm diameter, 1.6kg warhead (5.5 inch, 3.5 lb) could penetrate 200 mm (8 inches) of armour. Traveling at 10,000 metres/second (32.800 feet/sec) the the molten metal jet by the shaped charge war-head was over 1.5 metres (4.9 feet) long. There are reports of Panzerfaust jets penetrating the 2 inch (50-mm) armour on the side of a Sherman, passing through intervening personnel and equipment to burn their way clean through the armour on the other side. If the jet encountered fuel and ammunition on the way the effects could be catastrophic.[ii] In Normandy, hollow-charge infantry weapons (Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck- a scaled up German version of the bazooka) accounted for about 6% of allied tank casualties, By the time the allies were advancing into Germany the proportion had reached 34%. The Panzerfaust also accounted for a significant proportion of the13,700 tanks and assault guns which the Soviets admitted to losing in 1945 – particularly in close-quarter city fighting. In December 1943, the Germans instituted the Panzervernichtungabzeichen (tank destruction badge) worn on the upper right sleeve. To win the badge the recipient had to destroy a tank with hand-weapons (grenades, mines, satchel charge, Panzerschreck or Panzerfaust). Some 14,000-18,000 were issued to those lucky enough to survive. In addition to the losses imposed, the ubiquity of the Panzerfaust placed heavy constraints on how and where armour was used and made close infantry/armour co-operation essential. Operational research concluded that concerns about the Panzerfaust threat slowed the pace of the allied advance east of the Rhine by about 30%.[iii]

Needless to say, troops tried to improvise whatever means they could to protecting their tanks from the effect of the Panzerfaust’s shaped charges. Extra track, wheels, storage bins, logs and sand bags were attached to the sides and turret in hope of disrupting the jet before it reached the tank’s main armour. The Russians tired welding wire-mesh frames, and even bed springs, to their tank turrets.

![These photographs illustrate the lengths to which tank crew would go in using spare tracks, from whatever source,in their search for extra protection against German shaped-charge and high velocity rounds.]](https://milart.blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/add-on-track-protection-4.jpg?w=497&h=171)

These photographs illustrate the lengths to which tank crew would go in using spare tracks, from whatever source,in their search for extra protection against German shaped-charge and high velocity rounds.]

In February 1945, First Canadian Army undertook a number of experiments using a derelict Sherman and captured Panzerfaust. These trials were later continued by Canadian Military Headquarters in cooperation with the British Directorate of Tank Design (DTD). Solutions tested included: spaced armour alone; spaced armour backed by a filler such as cork, rock-wool or sand; angled plates to prevent the shaped charges fuze from working correctly; spikes mounted in plastic armour – the aim was to perforate the shaped charge’s cone as it struck and deform the jet; and mounting mesh screens – the purpose of which was to catch the warhead gently enough to stop it without detonating it.

The final report issued by the DTD on 14 May, 1945 does not make encouraging reading.

Spaced armour had to be at least 30 inches (75 cm) from the main armour to defeat the shaped charge – increasing the overall width of the vehicle by 5 feet (1.5 metres). A 3/4 inch (20 mm) spaced armour plate with a stand-off distance of 12 inches (30 cm) or less actually enhanced the shaped charge’s effect by optimizing its stand-off distance. Spaced armoured backed with 12 inches of cork or rock wool did not work. Spaced armour filled with 12 inches of sand usually worked, but added 5 to 9 tons to the vehicle’s weight.

Both angled plates and spikes showed promise against small rotating shaped charge shells, but not against heavy non-rotating charges such as the Panzerfaust 60 or the Stielgranate 41 round used with the 3.7 cm PaK 36. Mounting mesh screens worked to some extent with the relatively low velocity Panzerfaust (klein), which had a kinetic energy of only 440 ft/lbs. They failed to stop a Panzerfaust 60 with a KE of 3500 ft/lbs. It was not possible to devise a screen strong enough to stop the Panzerfaust 60, but gentle enough to prevent it from detonating.

Using small charges to disrupt the jet- a forerunner of reactive armour – was also considered. It was deemed “wholly impracticable” – as it was impossible at the time to make the charges sensitive enough to detonate in time to defeat the shaped charge, but not so sensitive that they would not be set off by chance blows or near-by explosions. The British obtained similar results in trials carried out in Normandy and Italy. A Panzerfaust could burn through the frontal armour of a Churchill (175mm), and even with mesh screens mounted, had no trouble penetrating its 79 mm side armour.

The Germans also used mesh screens, the so-called Thoma Schürtzen, but their main intent was to protect the tank’s undercarriage from anti-tank rifle fire.

The final conclusion was that the only certain defence against the Panzerfaust was to ensure the closest possible co-operation between armour and infantry. Despite the apparent ineffectiveness of the various improvised counter-measures, the Germans believed they were having some effect. They had begun to attack armoured vehicles by firing two Panzerfaust in quick succession, one to blow away any screening, the other to penetrate the AFV. According to a German report of 6 April, 1945 the Panzerfaust 150 was designed to overcome countermeasures. Its sharply pointed cap helped penetrate any screening, and it had a semi-circular cavity to achieve even deeper penetration. The War ended before it entered service but it influenced post-war Soviet and West German designs.[iv]

The above illustrations come a report prepared Major A.G. Sangster, the AFV Technical Development Officer at HQ First Canadian Army.

Bibliography

Library and Archives Canada

RG 24 microfilm C-5773 file 55/508/9

RG 24 Volume 9392

Copp T. ed, Montgomery’s Scientists Operational Research in Northwest Europe, WLU. Waterloo, 2000

Gander, T.J Field Rocket Equipment of the German Army, Almark London 1974

Rottman G.L, Panzerfaust and Panzerschrek, Osprey 2014,

Weeks, J, Men Against Tanks, David & Charles, London, 1975

Notes

[i].Rottman G.L, Panzerfaust and Panzerschrek, pp 18-19,21, 28.

[ii]. Ibid pg. 54;Gander, T.J Field Rocket Equipment of the German Army, pp.55-6

[iii].Copp T. ed, Montgomery’s Scientists Operational Research in Northwest Europe, pp.553-60

[iv].Library and Archives Canada, RG 24 microfilm C-5773, file 55/508/9, RG 24 Volume 9392

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

The ‘Priest’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier, in Canadian Service, 7 August to 30 September 1944

by Mark W. Tonner

Introduction

In North-West Europe, during the later half of 1944 and into 1945, the Canadian Army used two types of armoured vehicles that came to be known as a Kangaroo. The Kangaroo was the world’s first fully tracked ‘Armoured Personnel Carrier.’ This ingenious concept was devised by Lieutenant-General G.G. Simonds, the General Officer Commanding, II Canadian Corps, as he searched for a way to reduce the high casualty rate amongst his infantry. His solution also allowed them to move at ‘tank speed,’ along with their supporting tanks, from start line too final objective.

‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers with troops of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division aboard, on the evening of 7 August 1944 prior to the launch of Operation TOTALIZE. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

Birth of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier

Near the end of July 1944, General H.D.G. Crerar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, First Canadian Army, had instructed Lieutenant-General Simonds, to prepare plans for a breakthrough in the Canadian sector, telling Simonds to, “draw up plans for an actual attack, axis Caen-Falaise, objective Falaise” (Operation TOTALIZE, 7-10 August). On 31 July, Simonds verbally gave Crerar his appreciation of the situation and outline plan, with Simonds emphasizing that:

the ground is ideally suited to full exploitation by the enemy of the characteristics of his weapons. It is open, giving little cover to either infantry or tanks and the long range of his anti-tank guns and mortars, firing from carefully concealed positions, provides a very strong defence in depth”

On 2 August, Simonds put both his appreciation and outline plan on paper and sent it out to his divisional commanders. In his covering letter to the divisional commanders, Simonds wrote in part

“The infantry accompanying the armour to first objective in Phase One must go straight through with the armour. Arrangements have been made for about 30 stripped Priests’ chassis to be available to each of the infantry divisions (2nd Canadian and the British 51st (Highland)) operating in Phase One for this purpose …. The essentials are that the infantry shall be carried in bullet and splinter-proof vehicles to their actual objectives.”

This innovation was the first use of what have since come to be called armoured personnel carriers, in which infantrymen rode into battle mounted in vehicles with the same armoured protection and mobility as the tanks that accompanied them.

An example of the M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled gun, pictured here as No. 4 gun, “E” Troop, 78th Field Battery, 13th Canadian Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, in Normandy, July 1944. This particular vehicle (S215830) was itself converted to a ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, and subsequently was one of the initial 50 issued to the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, on 1 September 1944. Source: MilArt photo archive.

The concept of carrying troops into battle in specially adapted tanks had been tried as far back, as the Canadian Corps’ Amiens (France) offensive of August 1918, during the Great War of 1914-1919. Trials had been conducted in the United Kingdom during 1942-1943, in the use of armoured sleds carrying infantry, which were towed by tanks, and which was put into practice by the United States Army at Anzio (Italy) in early 1944. I Canadian Corps, at that time in Italy (1944), had also suggested the use of ‘stripped’ down universal carriers,1 towed by tanks, as armoured infantry carriers, in the attack. However, Operation TOTALIZE marked the first battlefield appearance, of specialized armoured troop-carrying vehicles of the sort, which had the same armoured protection and mobility as tanks.

On 31 July, Lieutenant-General Simonds sought to obtain American permission to modify the M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled guns, which were just being withdrawn from the 12th, 13th, and 14th Field Regiments, Royal Canadian Artillery, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. These regiments had been equipped with the M7s for the Normandy landings, of 6 June 1944, and subsequent bridgehead battles, but were now turning these into Ordnance, upon being re-equipped with towed 25-pounder equipments.2

This permission being obtained, the urgent task of converting these equipments was set in motion. On the evening of 31 July, Brigadier G.M. Grant, Deputy Director of Mechanical Engineering, First Canadian Army,3 was instructed by Crerar, to set up an organization to convert 72 M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled guns to armoured personnel carriers by 9 August. This date was soon however changed to 6 August with “as many as possible” by the night of 5 August. At noon on 1 August, Major G.A. Wiggan,4 Officer Commanding, 2nd Tank Troops Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, was called to the Deputy Director of Mechanical Engineering office at First Canadian Army headquarters. Here he was instructed to carry out the task of converting these 72 M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled guns into armoured personnel carriers. Major Wiggan was instructed to set up an ad-hoc Advanced Workshop Detachment5 (code named ‘AWD Kangaroo’) to carry out these conversions.

‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, with troops of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division aboard, on the evening of 7 August 1944, prior to the launch of Operation TOTALIZE. Note the driver’s vision aperture in the open position, with the driver seated above on the top of the upper front plate. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

The conversions were to be made in such a way that the Priests could be converted back into self-propelled guns. The process consisted of removing the 105-millimetre gun, with mount and mantlet, and all artillery related equipment, and welding armour plate across the gap left by the removal of the gun. The interior ammunition stowage bins, and crew seating, was also removed, resulting in a spacious interior. The additional armour plating that the previous artillery crews had added along both sides of the fighting compartment, for added protection, was retained. At the same time the radial engine was subjected to an overhaul (the 100-hour check), the M7 ‘Priest’ having a 450-horse power Continental R975 radial aircooled 9-cylinder aircraft engine that required a thorough check after every 100-hours of operation (the overhaul itself would normally take seven days to complete). Finally, the vehicle was given a general serviceability check of the transmission, differential, brake linings and running gear. Keep in mind that at the time of conversion, the original M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled guns, had been in constant action, from their early June landings in Normandy, up until the decision was taken to convert them into armoured personnel carriers, leaving very little time, for proper maintenance by the artillery crews, due to the urgent need, and demands made on them to provide artillery support, too on going operations. By the time of conversion, these equipments, were in quite rough mechanical shape, and the urgency under which they were converted, left little time, but for the most basic of mechanical repairs, in order to have them serviceable for the forthcoming Operation TOTALIZE.

On 2 August, ‘AWD Kangaroo’ was established within the Rear Maintenance Area of 21st Army Group,6 in two fields near Bayeux, France. This was about twenty miles (32-kilometres) from the start line for Operation TOTALIZE. It consisted of elements of fourteen Canadian and British, electrical and mechanical engineering units,7 and consisted of 250 all ranks, 250 all ranks, who pooled their efforts and skills into the project. The first crews arrived late in the afternoon and, by last light, had 14 vehicles stripped.8 The hours of work established were from 5:00 to 11:00 A.M., and 12:30 to 5:00 P.M., and 6:00 to 10:00 P.M. daily, but with the urgency of the situation, 4:00 A.M. to 11:00 P.M., was the norm. All Canadian and British electrical and mechanical engineering units within First Canadian Army were canvassed for electric and gas welding equipment, along with the tradesmen to go with them. Unlimited access to welding rod, armour plate, radial engine parts, oxy-acetylene welding sets and gases and radial engine overhaul stands were required.

‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, carrying troops of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, with tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, on the evening of 7 August 1944, moving to their start line prior to the launch of Operation TOTALIZE. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

The armour plate came from the ‘Help Yourself Park’ of “W” crocks (the name given to tanks salvaged from the battlefield that were declared beyond repair), and after this source was exhausted, steel plate from the Schneider Steel Works in Caen and from wrecked and stranded Naval craft on the beaches was tried. Both were found to be unsuitable, so mild steel ½-inch plate from the steel mills in the south of Caen was used. These plates were welded over the opening left by the removal of the gun, in the form of spaced armour, that is, one plate welded over the opening from the outside and one welded over the opening from the inside, with the space between the plates being filled with sand.

A brief description of the specifications of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier

The ‘Priest’ Kangaroo hull, was constructed of rolled and cast homogeneous steel, of welded assembly, and was 19-feet, 9-inches in length, 9-feet, 9¼-inches wide, and stood at a height of 8-feet, 4-inches, with a ground clearance of 17 1/8-inches. The armour of the upper front plate was a ½-inch thick, that of the lower front plate was 2 to 4 ½-inches thick, well the sides and rear plates were also, a ½-inch thick. The interior of the hull was divided into two compartments, the fighting compartment, and the rear compartment (or the engine compartment) which housed the power unit (engine) and transmission gear. The driver’s position, was located in the left-front of the fighting compartment. The driver was provided with a large vision aperture, with a small vision port protected by very heavy glass, for use, when the large vision aperture was closed, although most drivers preferred to keep the large vision aperture open in all but the heaviest enemy fire. They felt it was not really safe to drive using the small vision port only, their field of view was too restricted and their vehicle was often used in rather tight quarters. The driver was also provided with a removable windshield which could be fitted into the large vision aperture, when operating the vehicle, with the aperture in the open position. A large box was provided for its stowage, when not in use, which was mounted to the driver’s left, on the inside, of the front armour plate. The driver carried out opening and closing of this aperture, from within the vehicle.

A rear view of troops ‘embussed’ (loaded) in a ‘Priest’ Kangaroo. Note the thickness of the upper left-side additional armour plating, and the ‘absence’ of the basic pioneer tools, except for a lone shovel, on the engine compartment top plates. This particular vehicle, saw service as the No. 4 gun, “F” Troop, 43rd Field Battery, 12th Canadian Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, before conversion to that of a ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

Many of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroos retained their anti-aircraft/ground defence .50-calibre Browning heavy machine gun M2, heavy barrel, which was mounted in a ring mount, on the right-front corner of the fighting compartment, underneath which, on the hull side interior wall, stowage was provided for boxes of .50-calibre belted ammunition. About 60% of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroos retained their No. 19 wireless sets (a radio set) for communications. The No. 19 wireless set consisted of an “A” set for general use, and a “B” set for short range inter-tank work at the troop level, and an intercommunication unit for the crew. Access to the vehicle was gained by four pairs of grip bars, with two pairs being mounted on each side of the fighting compartment, which served as ladders to the fighting compartment. Access to the engine was provided through two engine compartment top plates, and through a set of rear engine doors, located below the rear plate of the upper hull. Located within the engine compartment, were four fuel tanks, with a total fuel capacity of 176 gallons. The ‘Priest’ Kangaroo had a road speed of approximately 25-miles per hour, and a cross-country speed of approximately 15-miles per hour. The suspension used on the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo, was the ‘Vertical Volute Spring’ type, which consisted of 12 wheels in six bogies, with three bogie assemblies per track. The two wheels in each bogie assembly were pivoted on arms against a vertical spring which was protected by the bogie carrying bracket. A return roller was mounted either on top of, or behind, the bracket, the entire bogie assembly forming a self-contained fitting unit.

External stowage bins and containers (for various tools,9 and equipment), were also provided for, along with the standard compliment of pioneer tools (shovel, crowbar, pickaxe, axe) and recovery/breakdown equipment (tow cable, jack and wood blocks) which were carried on all tanks. Four towing shackles were provided on the vehicle, two at the front, and two at the rear. A towing pintle was provided at the rear below the rear engine door, with a maximum towing capacity of 10,000 pounds.

Upon conversion, the majority of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, retained the markings of the artillery regiments, with which they had served as self-propelled guns, as can be seen in this photo. The markings above (‘D1’) and below (‘43’) the right-hand headlamp, indicate that this vehicle saw previous service as No. 1 gun, “D” Troop, 44th Field Battery, 13th Canadian Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

Directly below the ‘allied recognition star,’ which is painted on the right side of the fighting compartment, can be seen two pairs of grip bars, which were used to gain access to the vehicle, with another two pairs mounted on the left side, in the same position. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive.

The ‘Priest’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier in service

By the evening of 5 August, the 72 carriers were ready (with four more ready at noon on 6 August, which were held in II Canadian Corps reserve). Lieutenant-General Simonds, divided these 72 completed ‘Priest’ Kangaroos among the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and the British 154th (Highland) Infantry Brigade, of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, for Operation TOTALIZE.10 Each ‘Priest’ Kangaroo could carry approximately 10-15 fully armed infantrymen and their equipment, who ‘embussed’ (loaded) and ‘debussed’ (unloaded), over their armoured sides. Drivers for these converted ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, where found from No. 9 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion (which held Canadian Armoured Corps, and Royal Canadian Artillery reinforcements) and from the personnel and reinforcements carried by “E” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps,11 and from among those artillerymen of the three field regiments of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisional Artillery who had operated them (who were now surplus to their respective field regiments, as they had converted to towed guns), each ‘Priest’ Kangaroo ending up with a crew of one man, the driver. To maintain the 36 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos allocated to 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, an ad-hoc ‘Kangaroo’ Light Aid Detachment,12 of 31 all ranks (drawn from numbers 32, 33 and 34 Light Aid Detachments,13 Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) under Captain W.T.E. Duncan (formerly of No. 33 Light Aid Detachment, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers ), was established to service 36 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, for a supposed period of ten days to two weeks.

At 11:30 P.M. on 7 August 1944, for the first time in Canadian history, armour and infantry advanced to the attack with the infantry protected from the enemy small arms fire and shell splinters. At the same time they were able to keep up with their tank support, as all were moving forward on ‘tracks,’ at tank speed. This use of the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers was an immediate success. The infantry was able to obtain their objectives without suffering heavy losses from the enemy’s defensive machine gun and mortar/shell fire, while traversing the ground from start line too objective. The advance confirmed the effectiveness of this new tactical weapon. The mobility provided to the infantry by the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, along with the armoured protection, resulted in fewer casualties and greatly increased morale. The ‘Priest’ Kangaroos also proved effective in the role of delivering supplies forward to the infantry, and in the evacuation of casualties to the rear.

One of the 36 ‘Priest’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, allocated to the British, 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, for Operation TOTALIZE, carrying troops of the 7th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 154th (Highland) Infantry Brigade. Note the ‘HD 69,’ chalked onto the outside armoured plate welded over the opening left by the removal of the gun, which was used as a means of identifying what unit a ‘Kangaroo’ was carrying, for movement control purposes. The number ‘69,’ being the Arm-of-Service serial used by the 7th Argyll’s, within 51st (Highland) Infantry Division. Also of note, the sign in the lower right-hand corner of the photo, was used to indicate the location of the 7th Argyll’s battalion headquarters, when in a static location. Source: authors’ collection.

Their success in Operation TOTALIZE (notably, in the lowering of infantry casualties) was immediately followed up by their use during the continued drive on Falaise known as Operation TRACTABLE (14-16 August).14 It was quickly realized (as early as 20 August) however, that a stronger parent organization for these one-maned crewed carriers, and the ‘Kangaroo’ Light Aid Detachment, was needed, and so, on 28 August 1944, instructions were issued for the organization, on a temporary increment basis only, of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, and Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, under the direction of Headquarters First Canadian Army in First Canadian Army Troops Area. The temporary basis of the Squadron and Light Aid Detachment, was to be reviewed monthly.

Captain F.S. Corbeau, formerly of The Grey and Simcoe Foresters,15 was appointed Officer Commanding, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, and Captain W.T.E. Duncan16 (formerly the officer commanding the ad-hoc ‘Kangaroo’ Light Aid Detachment) was appointed Officer Commanding, the Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers17 (with effect from 1 September). The squadron, and attached Light Aid Detachment, was formed as an increment to Regimental Headquarters, 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), for the purposes of administration. Under the ‘Table of Organization’ issued on 24 August, the Squadron was to have four troops of 25 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos each, for a total of 100, and an overall personnel strength for the squadron of 131 all ranks. Again, the personnel were drawn from No. 9 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion,18 and from those qualified, of the 12th, 13th and 14th Field Regiments, Royal Canadian Artillery, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.

A column of ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, carrying troops of the 7th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 154th (Highland) Infantry Brigade (although the chalked ‘HD’ is barely visible beside the number ‘69’), moving toward their ‘forming up point’ for the start of Operation TOTALIZE. Source: authors’ collection.

On 1 September, Captain Corbeau’s squadron, took over 50 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos19 (half of his authorized establishment), from “E” Squadron, 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), from which, on 2 September, he divided the Squadron into four Troops, consisting of, No. 1 Troop – with 14 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, No. 2 Troop – with 12 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, No. 3 Troop – with 12 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, and No. 4 Troop – with 12 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, for which he only had 28 gunners (the designation used by the Royal Canadian Artillery, for a ‘Private), Royal Canadian Artillery, who were qualified ‘Driver Tank’, of which only 14 had any driving experience. With the help of borrowed personnel from “F” Squadron, 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment),20 on the night of 2/3 September, the Squadron moved, on it’s ‘tracks’, to a harbour area near Brionne, France, where they were to await instructions for a probable move back to Bayeux (France), to return to Ordnance their ‘Priest’ Kangaroos and be re-equipped with ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers. Once in harbour (Brionne), and while awaiting the order to proceed to Bayeux, to exchange their ‘Priest’ Kangaroos for the new ‘Ram’ Kangaroos, Captain Corbeau’s squadron, spent 3 to 7 September doing much needed maintenance. Since the night of 7/8 August, the ‘Priest’ Kangaroos had been in continuous use, supporting First Canadian Army operations in the drive toward Falaise and the closing of the ‘Falaise Gap’, there had been little time for proper maintenance to be carried out on them. However, late on the afternoon of 7 September, the Squadron received orders to move to Bolleville, France, and report to I British Corps, where Captain Corbeau learned that the Squadron would be taking part in the operation to capture Le Havre (Operation ASTONIA), in which operation they were to be involved with from 8 to 12 September, with the British 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, and 51st (Highland) Infantry Division.

Two of the 36 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, allocated to the British, 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (both of which appear to be empty), travelling ‘down’ the SINATRA route. This route had been cleared from the 154th (Highland) Infantry Brigade’s rear assembly area, forward to the brigade’s start line, by the British 274th Field Company, Royal Engineers, of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, prior to the launch of Operation TOTALIZE. Note the use of the Highland Division’s ‘HD’ and the number ‘49,’ which was the Arm-of-Service serial used by the 274th Field Company, on the route marker (SINATRA), in the lower right-hand corner of the photo. Source: MilArt photo archive.

On 13 September, the Squadron was ordered to concentrate at Bolbec, France, where tank transporters were to pick-up and move the ‘Priest’ Kangaroos to a harbour area near La Capelle (France). Upon arrival they came under command of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division for the capture of Boulogne (Operation WELLHIT). During this operation, the Squadron was split between the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, and the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, with 20 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos allotted to each, during various phases of the battle, from 17 to 22 September. On 23 September, the Squadron received orders that they were to be included in the capture of Calais (Operation UNDERGO), again, under command of 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, this time carrying the 1st Battalion, Canadian Scottish Regiment, throughout operations on 24 and 25 September. On 30 September, orders were received from Headquarters, First Canadian Army, that all ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, were to be turned into a British Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Workshop, in the Cassel (France) area. The Squadron’s ‘Priest’ Kangaroos were to travel to Cassel on their own ‘tracks’ where, once turned in, the drivers would proceed to Pierreval (near Rouen, France) where they were to pick-up new ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers from “F” Squadron, 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment). The issue of these ‘Ram’ Kangaroos was spread over 1-2 October. Once complete, on 2 October, the Squadron was ordered to concentrate at Mill, The Netherlands. Two troops made their way on their own ‘tracks’, while the other two troops traveled by tank transporter. Once at Mill, the Squadron came under command of VIII British Corps.

Within two weeks of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, having concentrated at Mill, The Netherlands, they were absorbed into the newly embodied 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, while a British sister regiment, the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, was also formed shortly afterwards. Each regiment was equipped with 106 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carriers, giving each regiment the capability of lifting an entire infantry battalion. A future article will deal with the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier, in Canadian Service, 3 October 1944 to 20 June 1945.

An example of a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, with which 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, was issued over the period of 1-2 October 1944. Source: authors’ collection.

As a closing note, on 29 August 1944, approximately ten ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, were issued to the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, from their supporting ‘armoured delivery squadron’ (“D” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment)). These ten ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, were used as ammunition/supply/troop carriers, within the division, with at least one (based on photographic evidence) being converted into an ‘armoured command post,’ by Headquarters, 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade. Unfortunately, the details of the fate of these ten ‘Priest’ Kangaroos, is rather sketchy, since they were all surplus to the vehicle entitlements, of the units in which they served, and were not ‘officially’ counted against a unit’s vehicle holdings.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Miss Courtney Carrier, for proofing reading and offering constructive criticism, and comments, on my draft copies of this article, and Bill Miller, for his constructive criticism, and comments, and Clive M. Law, for providing photos from the MilArt photo archives, and for publishing this article, and lastly, my wife, Denise, for her never-ending support.

Any errors and/or omissions, are entirely the fault of the author.

Notes

- The Universal Carrier (commonly known as the Bren Gun Carrier), was a lightly armoured tracked vehicle, which served in many different roles. It had no overhead protection, and its armour plate only afforded protection against shell splinters and small-arms fire.

- The Ordnance, Quick Firing 25-pounder (or just 25-pounder), was the standard field gun, with which the three field regiments of a Canadian infantry division, and one, of the two field regiments of a Canadian armoured division, was equipped with.

- The officer responsible for the maintenance and repair of First Canadian Army’s equipment.

- Major Wiggan was subsequently awarded a Member, Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his command of the ‘AWD Kangaroo,’ with part of the citation, for which, reading “His enthusiasm, initiative and driving force contributed very materially to completing in three and one-half days what appeared to be an impossible task in the time available” (awarded as per Canada Gazette dated 17 March 1945, and Canadian Army Routine Order 5466 dated 19 March 1945).

- An advanced workshop detachment, was a portion of a workshop, which occupied a position forward of its parent workshop’s main location, when the necessity of the situation required it.

- The Rear Maintenance Area of 21st Army Group, at this time was located around the French city of Bayeux, in Normandy, and contained all the static administrative and maintenance units, supporting the Second British Army, and the First Canadian Army, which were the two armies that made-up the 21st Army Group.

- From the Canadian, Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and from the British, Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

- The first priority on 3 August 1944, was the completion of a ‘pilot’ model, for approval of its design, which reached Headquarters II Canadian Corps at 6:30 P.M., that evening, for Lieutenant-General Simonds’ inspection.

- Although, in the initial rush of the ‘conversion’ production, many of the deficiencies in the servicing tools of the original M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled gun equipments, were never corrected.

- The delivery and issue of which was carried out by “D” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), the ‘armoured delivery squadron’ of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division.

- “E” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), was employed as the ‘Corps armoured delivery squadron’ of 2nd Canadian Corps Troops, and held reinforcement tanks and men to supply the needs of the armoured units which came under command and/or control, of Headquarters 2nd Canadian Corps.

- A Light Aid Detachment, was made up of members of the Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and was attached to a unit, to assist the personnel of the parent unit in first line repair of its equipment, in so far as that repair was outside the capacity of the unit, to inspect unit equipment and supervise and advise on unit maintenance, to assist the unit in recovering its equipment when damaged or stranded, to assist liaison between the unit and second line workshops, and to advise the unit on technical matters.

- Numbers 32, 33 and 34 Light Aid Detachments, had been respectively attached to the 12th, 13th, and 14th Field Regiments, Royal Canadian Artillery, while they were equipped with the M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled gun.

- At the end of Operation TRACTABLE, of the 76 ‘Priest’ Kangaroos originally provided, 61 were still ‘battle worthy,’ while the remaining 15 were ‘recoverable vehicle casualties,’ mostly caused by mechanical breakdown.

- Formally, the 26th Army Tank Regiment (Grey and Simcoe Foresters), Canadian Armoured Corps, which had been disbanded on 1 November 1943, with all of its personnel being absorbed into Canadian Armoured Corps reinforcement units in the United Kingdom, as future reinforcements for Canadian Armoured Corps units, in the field.

- Captain Duncan was subsequently awarded a Member, Order of the British Empire (MBE), for his untiring efforts, outstanding initiative, resourcefulness, perseverance, and technical ability, under extremely adverse administrative and operational conditions, in maintaining a high standard of ‘battle worthiness,’ of the ‘Priest Kangaroos, in operations from Falaise to Calais (awarded as per Canada Gazette dated 17 March 1945, and Canadian Army Routine Order 5466 dated 19 March 1945).

- With an approximate overall personnel strength for the light aid detachment of 60 all ranks.

- Was a component reinforcement battalion of No. 2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group, which was capable of holding approximately 1,500 reinforcements (of all arms and services).

- These ‘Priest’ Kangaroos had, by now, been stripped of radios, servicing tools, and pioneer tools, since initially first going into action on the evening of 7 August 1944, and for which, there was a dire shortage of spares parts.

- “F” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), was employed as the ‘Army armoured delivery squadron’ of First Canadian Army Troops, and held reinforcement tanks and men to supply the needs of the armoured units which came under command and/or control, of Headquarters First Canadian Army Troops.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below.

by Roger V. Lucy

In late 1942, the Canadian Department of National Defence (DND)’s Directorate of Vehicles and Artillery (DVA) began work at No.1 Proving Ground in Ottawa on a small tracked vehicle using largely Jeep automotive components. DVA anticipated that there was a potential requirement for the smallest practicable tracked vehicle, for use by airborne troops and in the Pacific theatre. The project was formalized by the Army Technical Development Board (ATDB), on 10 January, 1943, as project 49, and assigned to its proponent DVA. The vehicle came to be referred to successively as: the Bantam Armoured Tracked Vehicle, the Light Recce Tank, and finally as the Tracked Jeep. Its envisaged roles included: intercommunication (running messages over contested ground), armoured reconnaissance, and engaging unarmoured troops in airborne and combined operations. Follow-on versions of the vehicle were to be amphibious, with twin propellers for water propulsion; although fully laden, it had a very low freeboard.

One of two surviving Tracked Jeep Mk.I pilots now on display in the Canadian War Museum’s Lebreton Gallery. This example may be Pilot No.2, which underwent extensive reliability trials at No.1 Proving Ground, in Orleans, Ontario (just east of Ottawa). MilArt photo archives

The pilot was demonstrated in Ottawa in May, 1943. On 7 June, it was decided that further development of the vehicle would have to take place in the USA, and that the General Staff Specifications and the pilot Tracked Jeep should be sent to a firm there. The logical choice for this was Willy-Overland in Toledo, The Canadian Department of Munitions and Supply (DM&S)’s Army Engineering Design Branch (AEDB) gave Willys a contract to construct five prototypes, working under DVA’s supervision. Willys would provide the power train components, while Marmon-Harrington was contracted to provide the running gear, and body and do the final assembly. On 8 July the pilot was sent to Toledo. En route, on 10 July, it was demonstrated at US Ordnance’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds, in Maryland. There, despite its rather makeshift nature, pilot Tracked Jeep performed quite well. Initially it evoked little interest among the allies (although DVA suspected that US Ordnance was inspired by the Aberdeen demonstration to begin development of its rival T-29 amphibious light tracked vehicle – also based on jeep components).

Three-quarter front view of the Tracked Jeep prototype, note the prominent front radiator. No.1 Proving Ground technicians assisted by Victoria Foundry, located in Hull, Quebec, essentially handcrafted the prototype. The original prototype of the Tracked Jeep (or Bantam Armoured Tracked Vehicle) was assembled at No. 1 Proving Ground in the latter half of 1942. The photographs of this prototype were taken on 7 May 1943. MilArt photo archives