by Keith Wright, CD

The author joined the 1 Service Battalion in Calgary in the summer of 1978, as a private fresh from trades training in Borden. Sometime later that year the Commanding Officer decided he wanted a unit drum and bugle band and the call for volunteers went out. A Band Sergeant was brought in to train and conduct the band. During the winter/spring of 1978/79 we practiced twice a week in a little shack down the hill in Sarcee, Alberta. I remember that it wasn’t normally heated until we used it and we would practice in our parkas. By the summer we were starting to sound like a band.

In June 1979, while on concentration at CFB Wainwright (WAINCON 79) we brought our instruments and dress uniforms to the field. We practiced band drill and playing while marching on the parade square in Camp Wainwright. It also gave us a chance to get a break from the field and enjoy a shower.

Cap and collar badges of the 1 Service battalion band. Courtesy the author from a display he mounted in 1982.

At this time the band consisted of the Band Sgt (conductor), a Band Administration Officer, a Drum Major (Sgt), four snare drummers, two side drummers, a bass drummer, three glockenspiel players, three buglers, and two baritone buglers (which included the author). During Waincon there was a female augmentee from the Canadian Scottish Regiment playing the glockenspiel.

At this time the band consisted of the Band Sgt (conductor), a Band Administration Officer, a Drum Major (Sgt), four snare drummers, two side drummers, a bass drummer, three glockenspiel players, three buglers, and two baritone buglers (which included the author). During Waincon there was a female augmentee from the Canadian Scottish Regiment playing the glockenspiel.

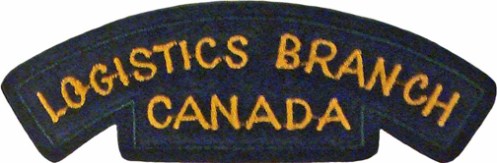

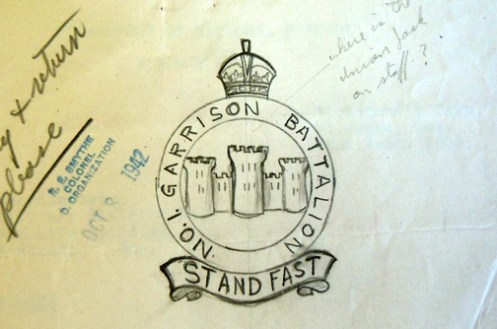

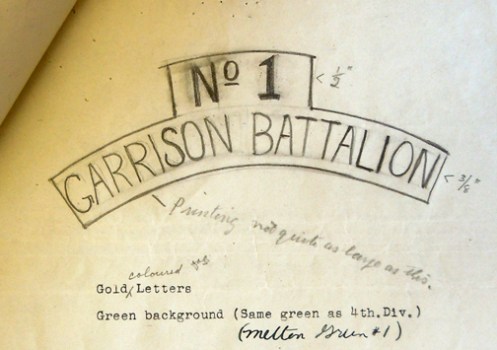

Proposed (early to mid 1970s) CF dress badge to be worn under the proposed CF LOGISTICS BRANCH shoulder flash. Author’s collection

In the spring of 1979 each band member was issued with a cap badge and pair of collars. 50 sets of these were purchased using unit funds. The cap badge is a very nice looking metal and enamel representation of the 1st Service Battalion crest. It measures 2 inches high by 1- 5/16 inches wide. It has a beret slider that is quite deep at 5/16 inches. A gold coloured crown inlaid with enamel – white upper, red middle and white on the bottom – surmounting the crest. Surrounded by ten gold maple leaves is an upright oval consisting of the gold and white ram’s head of 1 Canadian Mechanised Brigade Group on the diagonal colours of the Service Battalions (blue over yellow over red). This is enclosed by a blue border with the gold words: 1 SERVICE BATTALION – 1 BATAILLON des SERVICES. The bottom consists of a red banner with the gold motto: OFFICIUM SUPER OMNIA. The back is a gold-coloured, fine lined cross pattern. At about 5/16 inches from the bottom, under the beret slider, is the makers’ name, NORMANDY.

Our first command performance at which we wore the 1 Service Battalion Band cap badge and collars was (if I remember correctly) for the Battalion Change of Command Parade shortly after we returned from Wainwright. While there were a couple more performances the band died a quiet death through postings and a lack of interest from the new CO. When I left the battalion in the summer of 1981 all that was left was a single piper who played at battalion mess functions and parades. The piper wore the battalion band cap badge on his Glengarry.

The belt buckle worn with CF Service Dress utilises a collar badge as its device. Author’ collection

The collars are the same design and colours but half size. The ram’s head is less detailed and has more white in it. The back has two vertically mounted clutch pin fasteners. There is no name on the back of these collar badges. As a point of interest the collar badge is the same as the one used on the 1 Service Battalion belt buckle as they all came from the same supplier.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Clive M. Law

It has often been said that Truth is the first casualty of war as governments immediately limit the freedom of mass media. Twinned with this imposition is the increase in government propaganda and mass-advertising.

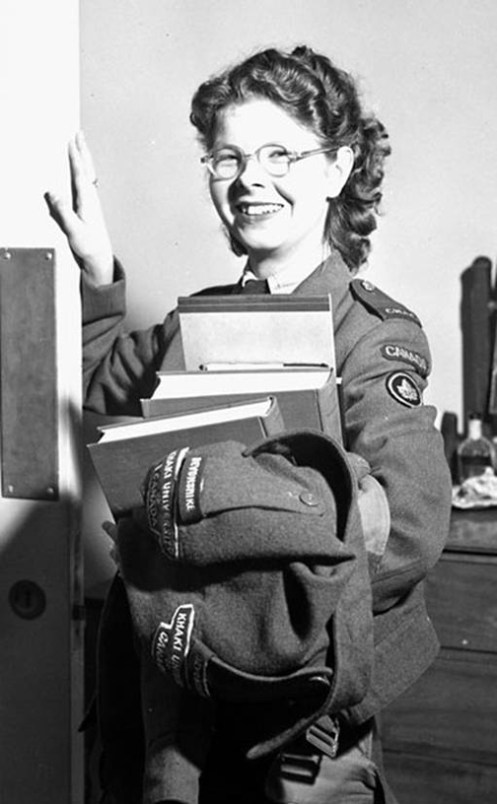

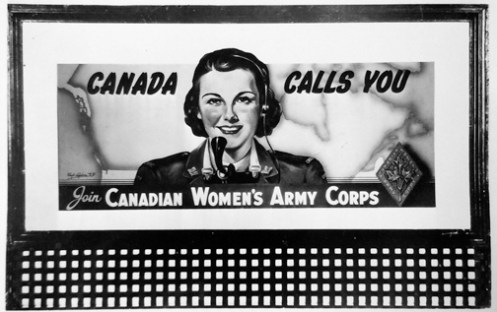

At the outbreak of the Second World War there was the expected rush to the colours by both the patriotic and those who, following the Great Depression, had few options and saw the war as an opportunity for regular meals and shelter from the coming winter. However, by 1941 the Canadian government, spurred on by the Army, was examining ways to increase recruitment. In August of that year the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) was raised, in response to the shortage of personnel caused by the increase in the size of Canada’s military. Although hesitant at first to employ women in uniform (or what one senior army officer called a “petticoat army”) these women soon proved their worth, by assuming duties that would release men for Active Service.

So successful was this ‘social experiment’ that the Army engaged in an advertising campaign to attract even more women. This campaign included press advertising, posters and the extended use of roadway billboards.

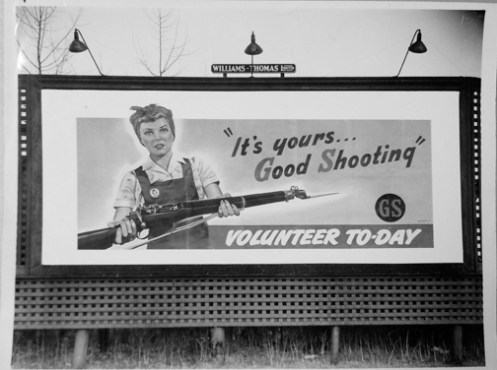

A photograph of an actual roadside billboard. Here a female factory worker, presumably from Long Branch, offers a Lee-Enfield rifle. The billboard plays on the “GS” badge which represented General Service (denoting a volunteer who has indicated a willingness to serve overseas) with Good Shooting.

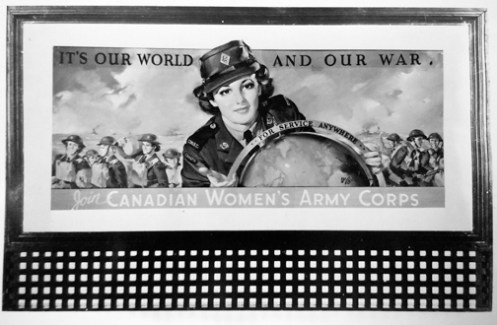

A mock-up showing the equality between men and women in uniform and indicating that both had the same motivation and goal.

Not only did the Army wish to increase the numbers of women in uniform they also wanted them to volunteer for General Service in order to serve at locations in Great Britain and, as needed, overseas at various headquarters.

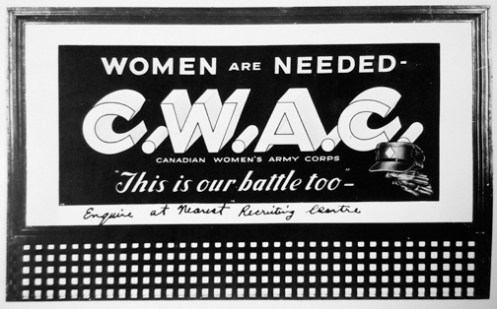

This mock up has the added text ‘Enquire at Nearest Recruiting Centre’ to maintain consistency with other billboards.

CWACs served in many occupations with clerical being the most common. In addition to drivers, some CWACs served in food service, instrument repair and machinery options. Short of actual combat there were many opportunities for women in uniform.

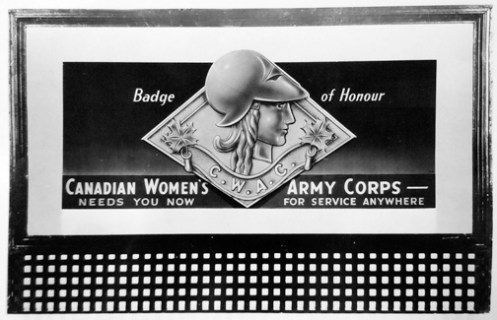

Another appeal to ‘Go Active’. In addition to encouraging new enrollment the billboards also encouraged existing CWACs to go to the next level by volunteering for oversea duty.

This mock up is leveraging the CWAC badge as used on the lapels of their uniform. The CWACs chose Athena, Goddess of War, as their symbol.

This mock up subliminally suggests that CWACs would only serve in Canada. The use of the model as a telephone operator would comfort many potential volunteers, and their parents, who saw this occupation as one that was suitable for women. Volunteers under the age of 21 required parental approval prior to enrolling.

This final mock up tugs on the patriotic heartstrings of young women. The badge is the result of an artist taking liberties with the CWAC cap badge.

The billboards’ locations were noted limited to roadways. Here, one is placed above a shop in a town’s shopping district.

Prospective recruits had to be in excellent health, at least 5 feet (152 cm) tall and 105 pounds (48 kg) (or within 10 pounds (4.5 kg) above or below the standard of weight laid down in medical tables for different heights), with no dependents, a minimum of Grade 8 education, aged 18 to 45, and a British subject, as Canadians were at that time. They were paid two-thirds of what the men were paid in the same occupation although this was later changed to four-fifths.

CWACs served overseas, first in 1942 in Washington, DC, and then with the Canadian Army in the United Kingdom. In 1944 CWACs served in Italy and in 1945 in northwest Europe. Following VE-Day they served with the Canadian Army Occupation Force (CAOF) in Germany. Approximately 22,000 women served in the CWACs and, of these, 3,000 served overseas. In August 1946 the CWACs were disbanded.

by Mark W. Tonner

Continuing on from the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2, of 27 October 2014

Although not a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, another conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, was to that of an armoured ammunition carrier, to replenish the tanks of armoured and armoured reconnaissance regiments, with ammunition, fuel, and personnel, during ‘active’ operations. This conversion consisted of the removal of the complete turret, with the turret ring and ball-race1 remaining in place, and the removal of the internal ammunition bins and racks. The No. 19 Wireless Set (a radio)2 was reinstalled in the left-hull pannier3, on the left of the bow machine gunner’s position, and the vehicle batteries were moved from the hull floor, up into the rear of the left-hull pannier. A circular 1-inch (14-millimetre) thick armoured plate, with a 28-inch (71-centimetre) square door (with two 14×14-inches (36×36-centimetres) hinged hatches), in the centre, was placed over the turret ring and ball-race (enabling the armoured plate to be rotated), with a 7-inch (18-centimetre) high splash plate4, being installed around the 28-inch (71-centimetre) square double hinged hatches. The drive shaft was also to be covered over, as in the conversion of Ram tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, as mentioned in the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2, of 27 October 2014. This would account for the references in some contemporary accounts of the drive shaft being covered over, as part of the initial conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, when in fact, only those ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, based on the conversion of ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, would have the drive shaft covered over.

Although, as mentioned in the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2, of 27 October 2014, the front towing hook was to have been removed from ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, as part of their conversion to that of a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier. As can be seen, this was not always the case, as evidenced by the towing hook assembly being still in place on the front of the lead ‘Ram’ Kangaroo in this photo. Source: Author’s collection

A ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment. Note the forward facing secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun mounted in the turret ring, and the vehicle tarpaulin, which as been pulled back from over a ‘tarp/bivouac’ support, which can be seen with one leg mounted in the front of the turret ring, while the other leg is mounted in the rear of the turret ring, with the centre pole of the

‘tarp/bivouac’ support, in between. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive

One innovation, which wasn’t part of any conversion of Ram tanks or Ram armoured gun towers, to that of armoured personnel carriers, was that of ‘tarp/bivouac’ supports, which were improvised by the crew members of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, themselves, for use with the large vehicle tarpaulin. These supports (or poles) either were crescent shaped, or had a downward leg at either end of a straight pole, and were mounted into any of the bolt holes left in the circular opening of the hull top, by the removal of the turret ring during the initial conversion of Ram tanks to either Ram armoured gun towers, or that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers. Once in place, the large vehicle tarpaulin could be put up over these, leaving an opening at the front for the crew to enter or exit the carrier, while keeping the elements out (i.e., rain or snow). These ‘tarp/bivouac’ supports, were normally used when the crew knew that they were going to be in a static position for a time, and could easily be cleared away and stowed before they had to move off again.

An example of crescent shaped ‘tarp/bivouac’ supports being used on a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive

Another example of the ‘tarp/bivouac’ supports in use, seen here on RED-CHIEF, a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive

On 14 October 1944, in a letter, in which First Canadian Army Headquarters, informed Canadian Military Headquarters (London), that 162 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers would be required, to form the Canadian armoured personnel carrier regiment, consisting of two squadrons of 53 carriers each, and a reserve of 50 armoured personnel carriers, an entitlement for six ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers, was allotted to the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps. These six ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers, were to be used as ‘command’ carriers, within the regiment. Two each, were to be held by Regimental Headquarters, “A” Squadron Headquarters, and “B” Squadron Headquarters. As of 21 November 1944, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, held four (CT159532, CT159702, CT1598715, and CT159896) of their entitlement of six ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers. At this time, First Canadian Army Headquarters decided that there was no priority for the issue of the remaining two, and that their issue be deferred until such time as either, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was under command of First Canadian Army6, or that the two were particularly requested. However, that being said, a fifth ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carrier, CT159891 (named MARION), was issued to the regiment sometime after 21 November 1944, and remained in service with 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, as a ‘command’ carrier. These ‘command’ carriers, would have been among those designated carriers that were fitted with a second No. 19 Wireless Set, or with No. 18, No. 22, or No. 38 Wireless Sets, as the need arose, as referred to in the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2, of 27 October 2014.

One of the ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers issued to 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, as a ‘command’ carrier, bearing the name MARION (CT159891), seen here, in June 1945, as the ‘Kangaroo’ of Major W.A. Copley, Officer Commanding, “B” Squadron, which he named after his wife Marion. Just above Major Copley’s head, on the top of the hull, can be seen, the 7-inch (18-centimetre) high, splash plate, which was installed around the 28-inch (71-centimetre) square double hinged hatches, in the centre of the circular armoured plate that was placed over the turret ring, as described in the text. Source: Bill Miller

As mentioned in the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 1, of 16 October 2014, part of the initial conversion of the Ram, Mark II tank, to that of a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier, was the repositioning of the No. 19 Wireless Set in the forward left-hull pannier, and as noted above, was also the case with the initial conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers. One interesting revelation which came to light, as 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment started receiving ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, was that, in some cases, the No. 19 Wireless Set was mounted to far forward in the left-hull pannier, thus overhanging the edge of the pannier and protruding into the carrier, which restricted the traverse of the bow ball-mounted .30-calibre Browning machine gun, to the right by 5-degrees. This overhanging of the edge of the pannier and protruding into the carrier, of the No. 19 Wireless Set, was also noted in those ‘Ram’ armoured ammunition carriers, that had been initial conversions of earlier Ram, Mark II tanks, which had an auxiliary turret, on the left front of the tank. Although the problems mentioned above, had been rectified in ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, converted to ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, by mounting the No. 19 Wireless Set over the transmission, between the co-driver’s, and driver’s position, as mentioned in the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2, of 27 October 2014. While awaiting a response to this latest problem (from Canadian Military Headquarters (London)) of the wireless set being mounted to far forward in the left-hull pannier, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, as an expedient measure, remounted the No. 19 Wireless Set in the forward right-hull pannier, of those carriers, in which the mounting of the wireless set in the forward left-hull pannier, was causing problems with the protrusion of the set into the carrier, or that was interfering with the operation of the bow mounted .30-calibre Browning machine gun. In January 1945, having been notified of what measures 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, had taken to rectify the problem with the No. 19 Wireless Set mounting, the Deputy Director of Mechanical Engineering, First Canadian Army7, in a letter dated 17 January, recommended to First Canadian Army Headquarters, that they make representation to Canadian Military Headquarters (London), that this work be done in the United Kingdom, prior to replacement ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, being shipped over to North-West Europe.

Although, as stated earlier, the No. 19 Wireless Set was to have been mounted in the forward left-hull pannier of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, the reality was, that it could, and was, mounted in one of the three positions, as mentioned above, either in the forward left-hull pannier, or in the centre-front over the transmission, between the co-driver’s, and driver’s position, or in the forward right-hull pannier. Those ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers that were eventually equipped with a second No. 19 Wireless Set, would have had it mounted in one of these three positions, as well.

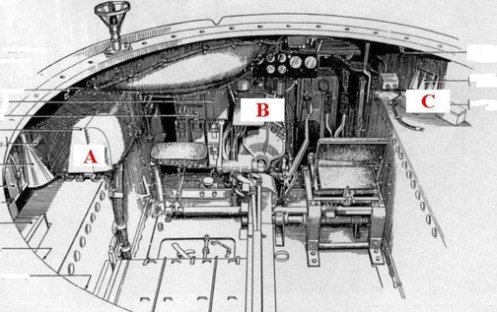

A diagram of the interior of a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier showing the three possible mounting positions for the No. 19 Wireless Set, as explained in the text.

A – in the forward left-hull pannier,

B – in the centre-front over the transmission, or

C – in the forward right-hull pannier. Source: Author’s collection.

Also, as of 14 October 1944, with Canadian requirements having been met, for the foreseeable future, for the conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to either armoured personnel carriers, armoured gun towers, or armoured ammunition carriers, Canadian Military Headquarters (London), agreed to provide the British with 330 Ram tanks8, subject to financial agreement, to meet their armoured personnel carrier needs, since on 11 October, Headquarters 21st Army Group, had authorized the formation of a second armoured personnel carrier regiment, to support the Second British Army. Having obtained approval from National Defence Headquarters (Ottawa), these 330 Ram tanks, were released to the British in mid-December 1944, with the understanding that any additional ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers required by First Canadian Army, would come from this source. This was accepted by the British War Office9, on 21 December 1944, under the understanding, that a financial adjustment would be made for any issued to First Canadian Army.

Infantrymen of the 2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, of 131st British Infantry Brigade, loading onto ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers of “B” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, near Dieteren, Holland, on 15 January 1945, during Operation BLACKCOCK. Note that the crew of the ‘Kangaroo’ in the foreground has left their pioneer tools strapped in place on the rear deck, common practice within the Regiment was to remove these, so that their infantry passengers wouldn’t make off with them for their own use. Source: Bovington Tank Museum (BTM 2293-A5)

A ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of “A” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, lifting infantrymen of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, in a thrust along the Cleve to Calcar road (Germany), on 16 February 1945, during Operation VERITABLE. Note the forward facing secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun mounted in the turret ring, with its barrel pointing skyward. Source: MilArt photo archives

Having spent November and December 1944, in Tilburg, Holland, readying themselves and their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers for battle, the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, resumed active operations on 8 January 1945, when two Troops from “B” Squadron lifted two companies of the British 1st Battalion, The Suffolk Regiment10, in an attack near Venray, Holland. From this attack to the end of hostilities in North-West Europe, on 5 May 1945, the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, were continually in action, carrying infantrymen of both the First Canadian Army, and of the Second British Army, into battle. Although the pace of these operations limited thorough maintenance, in a workshop setting, the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, were kept in serviceable condition throughout, by the valiant efforts the men of No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, which during the more fluid operations in which the regiment was involved in, would split into two sections. “A” Section, would accompany “A” Squadron, with “B” Section, accompanying “B” Squadron, to aid the crews of the regiments ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, in both maintenance and repair tasks, as the need arose. On 9 March 1945, in preparation for the forthcoming crossing of the River Rhine (Operation PLUNDER), “B” Squadron, was ordered into workshops, followed by “A” Squadron (on 11 March), for a major overhaul and refitting of their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers. By 20 March, both squadrons had returned from workshops, during which as part of the refitting process, their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, had been equipped with the new track extended end connectors. These end connectors greatly widened the width of the track, which in turn, further reduced the track pressure resulting in better performance on soft ground.

BUCKSHEE and another ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of “B” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, with infantrymen of “A” Company, The Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s), 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade, in Werlte, Germany, on 11 April 1945. Note the track extended end connectors on the outside edge of the right track, of both ‘Kangaroos’, and also the position of the secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun mounted in the turret ring. Source: MilArt photo archives

ENID, a Kangaroo of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, showing a closer view of examples of the crescent shaped ‘tarp/bivouac’ supports, the secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun (with the feed tray) mounted in the front of the turret ring, with its barrel pointing to the right, the track extended end connectors on the outside edge of the track, and the later style of bogie assembly, with the return roller mounted on a trailing arm behind the bogie assembly. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive

By April 1945, the Ram tanks upon which the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, was based, were now two to three years old. Prior to conversion to armoured personnel carriers, these Ram tanks had been used extensively in the United Kingdom for training purposes by units of the Canadian Armoured Corps, before being converted to ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, and having been, more or less in continuous use since arriving in North-West Europe, were now showing their age. Both the men of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, and those of No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, worked heroically to keep them maintained and ready for battle. As testament to the work of both the crew members, and of No. 123 Light Aid Detachment, in keeping their carriers in serviceable condition, and in response to some maintenance issues that were raised while his regiments armoured personnel carriers, were in workshops during March, Lieutenant-Colonel Churchill, Commanding Officer, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in a letter of 4 April 1945, to the Brigadier, Royal Armoured Corps11, First Canadian Army Headquarters, stated, that at no time had a Kangaroo failed to reach the objective, once an attack had commenced, unless it had been knocked out by enemy anti-tank fire, or suffered damage from enemy land mines, or had become stuck in mud, or had been stopped at the express request of the infantry commander of the infantrymen they carried. He also noted in his letter that since active operations had commenced for the regiment in January, neither of his Squadrons had failed to provide sufficient ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, to meet the requirements of the infantry, they were to carry. He also commented, that since January, only five of the regiments ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, had broken down due to maintenance problems prior to an attack, but that these breakdowns, had not impeded the attack or caused the infantry, not to have arrived at their objectives.

No. 1 Troop, “A” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, carrying infantrymen of “B” Company, The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, advancing on Groningen, Holland, on the morning of 13 April 1945. Source: 1 CACR Association & Archive

The end of hostilities in North-West Europe, on 5 May 1945, found all of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in Germany, with Regimental Headquarters, at Cloppenburg, “A” Squadron at Oldenburg, and “B” Squadron near Markhausen. On 15 May, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was ordered to concentrate at Enschede, Holland, where they were to ready their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, for turnover to Ordnance. The .30-calibre Browning machine guns, and wireless sets, along with all associated equipment, were to be removed, as well as all tank tools, and pioneer tools. The carriers were also to be cleaned and painted. On 11 June 1945, 52 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, of “A” squadron, along with three belonging to “B” Squadron, were returned to Ordnance, followed on 15 June, by the remaining 50 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, of “B” Squadron. Thus with having received notification of disbandment, on 12 June, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, and No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, were disbanded, with effect from 11:59 P.M., on 20 June 1945, under authority from Headquarters First Canadian Army Troops Area, dated 17 June 1945.

As of 28 July 1945, the Canadian Army Overseas12, held a total of 160 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, and an additional 20, that had been converted over from ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, to that of ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers. Shortly afterwards, those that were held in vehicle parks within Holland, were handed over (at no cost) to the Royal Netherlands Army, as they began the process of rebuilding themselves, in the wake of the Second World War. Those that were held in the United Kingdom, eventually passed into service with the British Army.

The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier in British service

With Headquarters 21st Army Group, on 11 October 1944, having authorized the formation of a second armoured personnel carrier regiment, to support the Second British Army, the British 49th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment (consisting of Regimental Headquarters, “A” Squadron, and “C” Squadron), was subsequently redesignated the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (consisting of Regimental Headquarters, “A” Squadron, and “C” Squadron), with an authorized strength of 20 officers and 456 other ranks, under command of Lieutenant-Colonel N.H. King, Royal Tank Regiment, and were concentrated at Vilvoorde, Belgium, on 1 November 1944, for organizational purposes. From 2 to 7 November, as the crews of the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, received their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, they set about the task of preparing them for action. On 22 December 1944, the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, joined their sister regiment, the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in the British 31st Tank Brigade13, of the British 79th Armoured Division14, with which they served until the end of hostilities in North-West Europe, in May 1945.

The British 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment was organized, under British War Establishment XIV/1643/1 ‘An Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, 21 Army Group,’ with effect from 16 October 1944, consisting of, a Regimental headquarters and two squadrons, with each squadron consisting of a Squadron headquarters with five armoured personnel carriers, an Administration Troop and four Troops, each consisting of a Troop headquarters with three armoured personnel carriers and three sections, each with three armoured personnel carriers. This armoured personnel carrier allotment to the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, gave it the capability of lifting two battalions of infantry as follows, using one Section – an Infantry platoon headquarters and three sections, using one Troop – an Infantry company headquarters and three platoons, using one Squadron – an Infantry battalion headquarters and four companies, and with using the whole Regiment – two battalions.

‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers of “A” Squadron, 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps. Source: Bovington Tank Museum (BTM 1115-B3)

Infantrymen of the British 3rd Infantry Division loading onto Kangaroos of the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, prior to an attack on Kervenheim, Germany, 2 March 1945. Source: Imperial War Museum (B 14972)

The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers for the British 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment came from Ram Mark II tank stocks in the United Kingdom, previously transferred to the War Office (see Note 8), and earmarked for conversion, by the British, to Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers. The majority of the Ram Mark II tanks transferred to the British, and then converted to ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, were mid-production Ram Mark II tanks bearing census numbers15 between CT40101 and CT40437, and those between CT40438 and CT40937, with auxiliary turrets but without sponson doors16, although the British also converted some of the earlier production Ram tanks they had received from the CT39000 series, which had sponson doors. Most of these had the earlier ‘Vertical Volute Spring’ type suspensions with the return roller mounted in the centre on top of each bogie assembly (see the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 1, of 16 October 2014). As mentioned earlier, an additional 330 Ram tanks, were released to the British in mid-December 1944, to meet their armoured personnel carrier needs.

Infantrymen of the British 3rd Infantry Division loading onto Kangaroos of the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, prior to an attack on Kervenheim, Germany, 2 March 1945. Courtesy Barry Beldom

A ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier of “A” Squadron, 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, carrying infantrymen of the 4th Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment, 130th British Infantry Brigade, on the outskirts of Ochtrup, Germany, 3 April 1945, prior to the liberation of Enschede, Holland. Source: Imperial War Museum (BU 2956)

From 8 November 1944, through to 5 May 1945, the British 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, like their sister regiment, the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, were actively involved in operations. In March 1945, because of the increasing demands made on the regiment, in the support of infantry operations, and at the recommendation of the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel N.H. King, “F” Squadron, 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was authorized, consisting of a Squadron headquarters with five armoured personnel carriers, an Administration Troop and four Troops, each consisting of a Troop headquarters with three armoured personnel carriers and three sections, each with three armoured personnel carriers. At the end of hostilities in North-West Europe, the 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment (Regimental Headquarters, “A,” “C,” and “F” Squadrons), was concentrated in the area of Hamburg, Germany, where on 10 June 1945, they began turning in their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. The 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was eventually disbanded effective 13 December 1945. The British Army retained their ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers in service, as armoured personnel carriers, or as driver training vehicles, to name but a couple of roles, until approximately 1955, when they were phased out of service.

‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers in postwar service with the British Army. Source: Bovington Tank Museum (BTM 2293-A1)

A ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier in postwar service with the British Army. Source: Bovington Tank Museum (BTM 2272-E1)

Conclusion

From their first use on the night of 7/8 August, 194417, through to the cease fire on 5 May, 1945, ‘Kangaroo’ armoured personnel carriers had been in the van of both major and minor assaults carried out by the infantrymen of 21st Army Group. The problem of lowering infantry casualties and moving the infantry at ‘tank’ speed from start line to the final objective, had been solved. The tactical handling of infantry in the ‘advance’, working with tanks, had been revolutionized by the advent of the ‘Kangaroo’ armoured personnel carrier.

Part of the Commanding Officer’s (Lieutenant-Colonel Churchill) address to 1st Canadian Armoured Carrier Regiment, on 11 May, 1945, best sums up the story of the ‘Kangaroo’ in Canadian service:

“ ……we have also been instrumental in saving the lives of countless soldiers who, without the Kangaroos, would have had to advance on foot unprotected from enemy fire. It is most comforting to reflect that many Canadian and British soldiers are alive today because of this Kangaroo Regiment.”

The original concept of the ‘Priest’ and ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers is still in use today by the Canadian Army, in the form of the Light Armoured Vehicle (LAV) III, although the Light Armoured Vehicle (LAV) III is an eight-wheeled vehicle, its function is that of an armoured personnel carrier for the infantry, still adhering to the phase of 1944 “The essentials are that the infantry shall be carried in bullet and splinter-proof vehicles to their actual objectives.”

Any errors and/or omissions, in Parts 1, 2, and 3, of ‘The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier,’ is entirely the fault of the author.

Bibliography:

Law, C M, Making Tracks, Tank Production in Canada, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2001

Library and Archives Canada, Records Group 24, National Defence, Series C-3, Volume 14301, Reel T-15430 and T-15431, Volume 16317, Volume 14995, and various other Files/Volumes – Records Group 24, National Defence

Lucy, R V, Canada’s Pride, The Ram Tank and its Variants, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2014

Knight, D, Tools of the Trade, Equipping the Canadian Army, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2005

Ramsden, K R, The Canadian Kangaroos in World War II, Ramsden-Cavan Publishing, Cavan, Ontario, 1998

Roberts, P, The Ram Development and Variants, Volume 1, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2002

Roberts, P, The Ram Development and Variants, Volume 2, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2005

The National Archives Kew, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom – WO 24 – War Office: Papers concerning Establishments – Sub Series WO 24/954 – War establishments – 1945 January-March – An Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, 21 Army Group, War Establishment XIV/1643/1 (4 pages).

Tonner, M W, The Kangaroo in Canadian Service, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2005

Notes:

- The metal rings, within the turret ring, which have a circular track inside of them, in which the ball bearings enable the rotation of the turret.

- The No. 19 Wireless Set consisted of an “A” set for general use and a “B” set for short range work and an intercommunication unit for the crew. The No. 19 set had a maximum voice range of 10-miles (16-kilometres) and a maximum morse range of 15½-miles (25-kilometres).

- On a Ram tank, the hull pannier, was the armoured portion of the hull which extended outwards above the tracks to the outer edge of the track.

- An armoured plated lip.

- In error, in early October 1944, CT159871, was issued to the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, from “F” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps, but stayed in service with the regiment throughout the remainder of the war, with “B” Squadron Headquarters.

- At this time, the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was under command of the Second British Army.

- The officer responsible for the maintenance and repair of First Canadian Army’s equipment.

- These were in addition to the 446 Ram Mark II tanks that had been transferred to the British earlier, in exchange for Sherman tanks from British stocks, as agreed upon at a meeting between Canadian Military Headquarters (London), and the British War Office, which was held on 22 October 1943.

- The British War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army, until 1964, when its functions were transferred to the British Ministry of Defence.

- A component of the British 8th Infantry Brigade, of the 3rd Infantry Division.

- The Brigadier, Royal Armoured Corps, First Canadian Army Headquarters, was the advisor to the General Officer Commanding -in-Chief, First Canadian Army, and officer responsible for all matters dealing with armoured formations and units, within First Canadian Army.

- The Canadian Army Overseas was the name given to that portion of the Canadian Army that served in the United Kingdom and Europe, during the period of the Second World War.

- Which on 2 February 1945, was redesignated the 31st Armoured Brigade.

- The British 79th Armoured Division operated specialized armoured vehicles modified for specialist roles.

- In order to provide a positive means of identifying individual vehicles, every Canadian Army vehicle was given a separate serial number, commonly referred to as census number. In the case of the Ram tank, this number was preceded by the prefix letters “CT,” the letter “C” denoting the vehicle as Canadian, and the letter “T” denoting that the vehicle was a tank. These census numbers were normally stenciled onto the vehicle in white letters 3½-inches (9-centimetres) high.

- A door located in the centre of the left and right hull side.

- See the ‘Priest’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier, in Canadian Service, 7 August to 30 September 1944, of 28 August 2014.

The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 2

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

By Capt Keith Wright CD

Air Cadet League Officer Uniforms

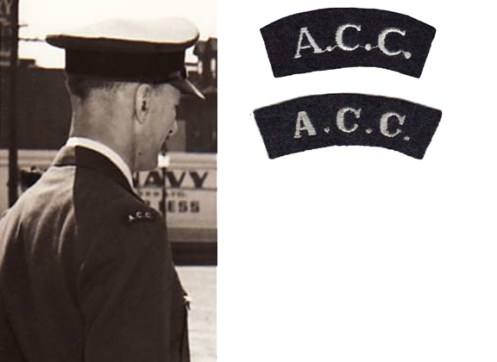

From the formation of the Air Cadet Corps on 15 Nov 1940 until 1943, officers of Air Cadet Squadrons were not commissioned but held an Air Cadet League warrant. Officers and adult First Class Warrant Officers wore the RCAF Officer Uniform with Air Cadet Cap Badges, Collars, Buttons, Squadron shoulder flashes and shortened rank that did not go all the way around the sleeve. They could also wear medal ribbons and aircrew wings.

Air Cadet Corps Officer Uniforms

On 22 April 1943 the Governor General-in-Council authorized a further component of the RCAF known as the “Air Cadet Corps” in which qualified persons could be appointed to commissions and shall not be deemed to be on active service. Commissioning and training courses started in earnest in the summer of 1943. They wore the RCAF officer dress uniform and cap badge, which in most cases would have been a private purchase from a tailor as that was the norm for officers at the time.

Air Cadet Corps Distinguishing Badge 1943

In the Air Force Routine Orders (AFRO) 2471/43 dated 26 Nov 43 Badges, Distinguishing – Air Cadet Corps, it states:

- A badge, similar in colour and design to the present officers’ type “Canada” badge, bearing the initials “A.C.C.” has been authorized for wear by R.C.A.F. Air Cadet Corps officers.

- These badges must be worn at all times in accordance with dress regulations, on both sleeves of the jacket and greatcoat, the top of the “ground” being one-half inch below the shoulder seam.

- Badges may be obtained by officer personnel on prepayment, at a cost of three cents per pair. Air Cadet squadrons are to submit demands by letter to C.H.Q., along with a cheque to cover the cost. When approval has been given, these demands are to be passed to the appropriate equipment depot to supply direct to the air cadet squadrons.

Top – Pattern 1 has thinner, more rounded, slightly larger letters and a fine black backing material.

Bottom – Pattern 2 has thicker, less rounded, slightly smaller letters and a coarse white mesh backing material.

AFRO 2122/44 dated 29 Sep 44 Badges, Distinguishing – RCAF (Air Cadets) states:

- AFRO 2472/43 is hereby cancelled and the following substituted.

- Badges, arm, distinguishing, “ACC”, similar in colour and design to the present officers’ type “Canada” badges, are authorized for wear by officers of the R.C.A.F. (Air Cadets).

Air Cadet Corps Distinguishing Badge 1945

It is not known if this is just a name change from RCAF Air Cadet Corps to RCAF (Air Cadets) or if the badge also changed from A.C.C. to ACC without the periods as no badge like that has been seen.

AFRO 152/45 dated 26 Jan 45 Badges, Distinguishing – RCAF (Air Cadets) it states:

- AFRO 2122/44 is hereby cancelled and the following substituted.

- Badges, arm, distinguishing, “Air Cadets”, similar in colour and design to the present officers’ type “Canada” badges, are authorized for wear by officers of the R.C.A.F. (Air Cadets).

The following photo of an officer wearing the AIR CADETS flash is in a No. 386 Sqn photo album from a picture taken at the April 1948 Annual Inspection. In other photographs from the 1947-48 year the officers appear to be wearing the AIR CADETS flash but the pictures are not clear enough to be certain. Pictures from the following year show the officers wearing the RCAF CANADA flash or nothing.

This badge is similar in shape & make to A.C.C. Pattern 2 and has a coarse white mesh backing material.

While it fits the description of the 1945 badge, this picture (below) of cadets from No.185 Olds Sqn wearing this same style badge in 1955 appeared in the 1956 Air Cadet Annual. So the above badge could have also been a proposed air cadet shoulder badge before the introduction of the standardized Air Cadet CANADA flash.

RCAF (Air Cadets) Distinguishing Badge, 1946(?)

This badge is one of a pair worn with the eagle facing backwards. It has a fine black backing material.

As no information on this badge is known and as no pictures have at this point come to light it is thought that this badge is possibly a proposed prototype or trial badge. Its similarity to the following badges seems to lend credence to that theory.

RCAF (Air Cadets) Distinguishing Badge, 1947

No official information on these badges is known and as the only pictures at this time are from the 1947 time period it is thought that this badge is possibly a trial badge. Photo evidence shows that it was never in general use or favour and was definitely replaced by April 1948.

F/O E.A. Anderson, CO of No.211 Ottawa Kiwanis Sqn, wearing the 1947 distinguishing badges at his squadron’s annual inspection. The picture is from the cover of the Canadian Air Cadet September 1947 issue.

AFRO 222/48 dated 16 Apr 48 AIR CADET BADGES – OFFICERS; states:

- The present cloth shoulder badge worn by officers of the RCAF (Air Cadets) has been replaced by a collar badge.

- This is a small gilt metal badge in the form of an eagle surmounted with a maple leaf and inscribed with the letters “R.C.A.C.” underneath.

- The badge is to be worn on both collars. The bottom of the badge is to be one inch above the step opening of the collar; the vertical axis of the badge is to be parallel to the inside (rolled) edge and midway between that edge and the outside edge of the collar.

The existence of this metal collar badge is unknown at this time, as are details such as size or if they came in a left & right pair. From then on RCAF Officers working with Air Cadet Program wore the same uniform as regular RCAF Officers with just the standard CANADA distinguishing badges.

If anyone has any more information or pictures on these or other badges worn by the RCAF Officers of the Air Cadet Corps please contact me at kwright5@shaw.ca.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

By Richard J.S. Law

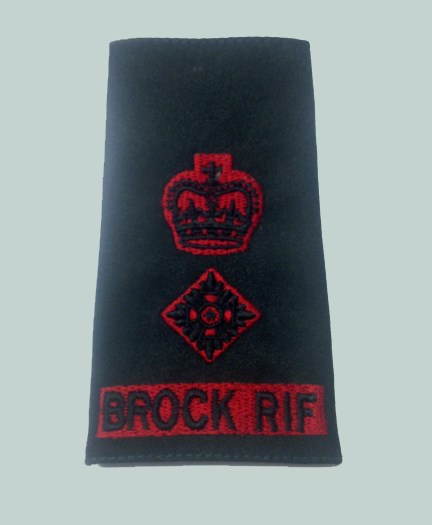

Following the announcement by the Minister of National Defence during the summer of 2013 that the Canadian Army would revert to traditional rank nomenclature for certain trades and units, the adoption of Divisions to replace Commands (grouped by regions), and the re-adoption of “Pips and Crowns” for officer ranks, some units were left to redefine their Regimental traditions of dress.

Particularly affected were those with distinctive devices such as Guards regiments who traditionally wear the Star of the Order of the Garter rather than the Star of the Order of the Bath, as well as blackened devices for Rifle regiments. Specific regimental patterns were not be supplied by the Crown, and would have to be acquired by the units using their own funds.

From the period of March to November 2014, The Brockville Rifles undertook discussion on the appropriate pattern to be selected for their officers, remaining in line with its pre-1968 traditions. The regimental museum, curated by Maj (ret’d) Roger Hum, was instrumental in this process, as was the regimental senate who offered advice and opinion on the options available.

The regimental museum offered historical examples to the Commanding Officer, LCol M.S. Herron, for review. The first sample, provided as a concept, was a crudely cast copy in the appearance of pewter, and having the improper dimension requirements of 23mm x 23mm. This example, and particularly the definition of “pewter”, became a hurdle to selection in the following weeks. As no Rifle regiment could provide a definition of “pewter” as a description of the device, help was sought from the collector’s market via social media. London, Ontario-based collector, Mr. Michael Reintjes supplied a picture showing stark variations of “pips” worn by the Oxford Rifles during the Second World War, demonstrating the variety of construction, material and level of blackening, or lack thereof.

Once the picture was circulated to those involved in the final decision, supporting documentation was sourced from archived dress instructions. These instructions stated that shoulder devices were to be “blackened”. A consensus was achieved that wartime usage of blackened device seems to have been conducted at the unit, or even individual level, using whatever shoulder devices were available and which were blackened by the use of locally available paint. The “pewter” appearance would have been the result of wear, where the paint would expose the original metal colour on the relief of the star or crown. The Adjutant took it upon himself to spray paint an issued Logistik Unicorp star with flat black paint and the judicious use of steel wool to expose the relief. Although this option was presented to the unit as a cost saving alternative, it was quickly dismissed in order to maintain uniformity and standardization

The initial samples provided by Penny’s in “shiny gun metal”, of note is the improper Star of the Bath with ‘Ich Dien’ scroll.

The CO, fond of samples showing exposed relief initially sought samples from Penny’s Ltd., of Thunder Bay. The first samples were described as “shiny gun metal”. The general consensus of the regimental senate was that the darkened silver was inappropriate and these were removed from further consideration.

The second sample from Penny’s in gloss black finish. The crown on the left was polished using steel wool to show relief.

In the June to August time-frame back and forth correspondence with Penny’s followed. Penny’s, submitted a second sample in gloss black which was of higher quality and displayed finer detail. Although these were well made, the red wool backing to be worn in conjunction with the insignia was, in fact, felted paper of poor quality and was rejected in favour of a flat black device which matched the blackened shoulder titles. Additionally, the crown was slightly different in shape and detail to that being issued by Logistik Unicorp.

Crowns submitted by Penny’s: on the left from the second sample run, and on the right a third sample run. The background material within the crown was deemed to be too dark, nearing purple.

In late August, the Ottawa firm of Guthrie Woods Ltd., was contacted to provide samples. Their crown, being of the same pattern as the issued device, was favoured and the stars exhibited crisp detail. On 18 September 2014, a decision was made by the Commanding Officer to purchase metal devices pips and crowns from Woods. An initial order of 25 pairs of stars and 10 pairs of crowns was placed by the Officer’s Mess. These are to be stocked by the regimental kit shop for officers to purchase, following an initial issue. The decision for cloth slip-ons to be worn on the undress shirt and overcoat was sourced to Penny’s of Thunder Bay. The delivery of these officer’s slip-ons was delivered on October 28th, 2014.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Mark W. Tonner

Continuing on from the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo Armoured Personnel Carrier, Part 1, of 16 October 2014.

On 9 October, a conference was held at Headquarters 21st Army Group, with, in attendance, representatives of Headquarters 21st Army Group, First Canadian Army Headquarters, and Second British Army Headquarters, to discuss armoured personnel carrier units. It was decided that such units were required to –

a.) – enable infantry in vehicles to accompany armour through areas still subject to fire from enemy weapons, thus assisting in preventing the enemy separating our armour and infantry

b.) – enable infantry to reach their objective more rapidly that at present possible by use of (i) armour protection to allow them to get closer to our own bomber targets whilst the latter are still being attacked. (ii) speed of the vehicle to reduce the time taken to reach the objective from the start line.

It was also agreed, that the squadrons of armoured personnel carrier regiments, must be organized to lift complete infantry battalions or subunits thereof. Therefore, it was agreed that an armoured personnel carrier regiment be organized and consist of a Regimental headquarters and two squadrons, with each squadron consisting of a Squadron headquarters with five armoured personnel carriers, an Administration Troop and four Troops, each consisting of a Troop headquarters with three armoured personnel carriers and three sections, each with three armoured personnel carriers.

This armoured personnel carrier allotment per regiment, was based on:

one Section (with three armoured personnel carriers)

– able to lift one infantry rifle platoon complete, with three armoured personnel carriers

one Troop (with 12 armoured personnel carriers)

– able to lift one infantry rifle company headquarters, with two armoured personnel carriers

– able to lift three infantry rifle platoons complete, with nine armoured personnel carriers

– one reserve armoured personnel carrier

one Squadron (with 53 armoured personnel carriers)

– able to lift one infantry battalion headquarters, with three armoured personnel carriers

– able to lift four infantry rifle companies complete, with 48 armoured personnel carriers

– two reserve armoured personnel carriers

one Regiment to consist of two Squadrons, with a total armoured personnel carrier strength per regiment of 106 armoured personnel carriers

It was also agreed, that each armoured personnel carrier regiment, should also have a reserve of 12 additional armoured personnel carriers, one for each of the regiments eight Troops, and two per squadron, and that squadrons, as far as possible, were to be administratively self-sufficient. Each regiment was to have an attached Light Aid Detachment (one officer and 52 other ranks, consisting of a headquarters and two sections, one section to each squadron) and a Signal Troop (one officer and five other ranks). The strength of each regiment was to be 25 officers and 522 other ranks (including the Light Aid Detachment and Signal Troop). The possibility of adding two more squadrons to each regiment was also discussed, and it was agreed that this would be put off for the time being. Eventually, the proposed two additional squadrons per regiment were dropped. With Headquarters 21st Army Group having come to the decision that two armoured personnel carrier regiments would be formed, one in the First Canadian Army, and the other, in the Second British Army, First Canadian Army Headquarters, informed Canadian Military Headquarters (London), on 14 October, that 162 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers would be required to form the Canadian armoured personnel carrier regiment, consisting of two squadrons of 53 carriers each, and a reserve of 50 armoured personnel carriers.

A ‘Ram’ Kangaroo of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, in support of 12th British Corps operations, in Holland, during mid to late October 1944. CT160141, was one of the initial issue of ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers to the squadron, having been received from “F” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), on 2 October 1944. Courtesy of Bovington Tank Museum (BTM 2293)

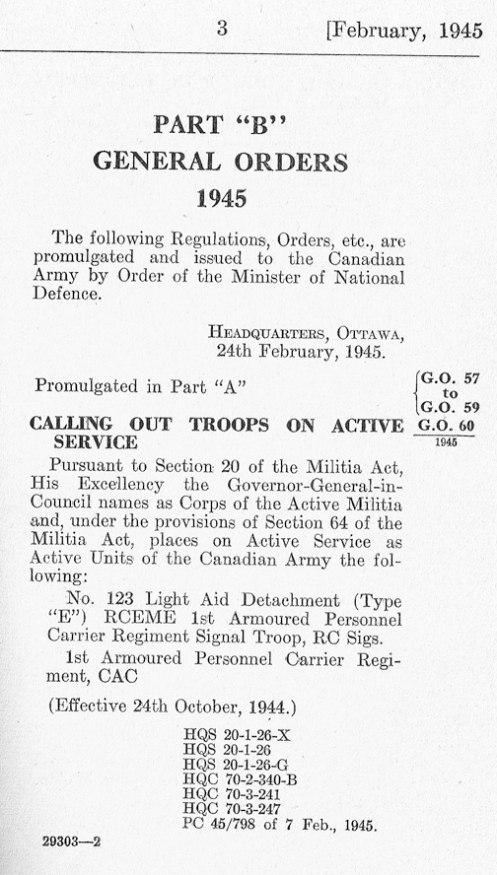

On 19 October 1944, Brigadier C.C. Mann, the Chief of Staff, First Canadian Army Headquarters, sought out the approval of Lieutenant-General G.G. Simonds, the Acting/General Officer Commanding -in-Chief, First Canadian Army1, for the authority to disband the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, and the Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers2. At the same time, the authority to form the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, and No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, was also asked to be approved. Having obtained Lieutenant-General G.G. Simonds’ approval, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, and the Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, were disbanded, effective 11:59 P.M., 23 October 1944. At the same time, the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, and No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, were authorized to be formed, with effect from 00:01 A.M., on the morning of 24 October 1944.

General Order Number 60 of 1945, under which the embodiment of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, and No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, was officially announced by Army Headquarters, Ottawa, on page 3 of Part “B” General Orders 1945, dated 24 February 1945. Authors’ collection

Although, as stated above, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps, was disbanded, effective 11:59 P.M., on 23 October 1944, but, since they were at that time involved with active operations, in support of the British 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, in the Moergestel, (Holland) area, they were in reality, absorbed into the newly created Canadian armoured personnel carrier regiment, as “A” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, under command of Captain Corbeau. Lieutenant-Colonel G.M. Churchill3 was appointed Commanding Officer, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, Canadian Armoured Corps, with Major F.W.K. Bingham4 being appointed Second-in-Command5. Lieutenant D.H. Simpson6, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, was appointed Officer Commanding, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, with Captain W.T.E. Duncan7, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, being appointed Officer Commanding, No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

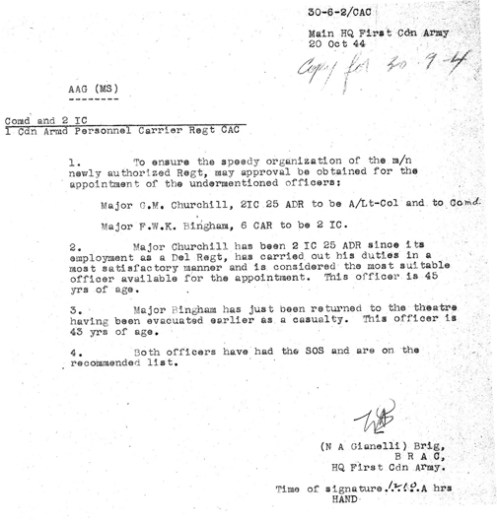

Letter from the Brigadier, Royal Armoured Corps, First Canadian Army Headquarters, to the Assistant Adjutant General First Canadian Army Headquarters, seeking approval for the appointment of Lieutenant-Colonel G.M. Churchill, and Major F.W.K. Bingham, as the Commanding Officer, and second-in-command, respectively, of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment. Authors’ collection

On 24 October, Regimental Headquarters, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was established in Antwerp (Belgium), to begin the process of organizing the regiment, with new personnel for the regiment being quartered in Rumst (Belgium), under control of Major Bingham (the regiment’s second-in-command), as they arrived to fill-up the positions in the organization of the regiment. On 28 October, Lieutenant-Colonel Churchill was informed that the regimental organization was to be completed by 6 November, followed, on 29 October, by the news that the regiment was to come under command of Second British Army on 1 November 1944. Arrangements were set in motion for the whole of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, to concentrate in the area of Tilburg (Holland). “A” Squadron’s support of 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division operations having been completed, were concentrated at Tilburg (Holland) on 30 October. Also, on 30 October, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, was informed by First Canadian Army Headquarters, that 106, .30-calibre Browning machine guns, had been released to the regiment, and were awaiting pick-up at 3 Sub Depot, 14 Advanced Ordnance Depot, Royal Army Ordnance Corps8. These additional .30-calibre Browning machine guns, were to be mounted, one a piece, on the outer edge of the circular hole left in the hull top, by the removal of the turret during conversion, on each of the regiment’s 106 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers. The idea, was to use one of the bolt holes left by the removal of the turret ring, as a mounting point for the machine gun. These guns were picked up by the regiment on 1 November, from which point, Captain S.F. Rook, the regiment’s Technical Adjutant9, and Captain Duncan, Officer Commanding, No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, set about to devise a suitable device for the mounting of these guns, on the outer edge of the circular opening in the hull top of the regiment’s 106 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers.

In an effort to minimize the potential hazard of infantrymen being exposed to shell splinters, or enemy fire, through the circular opening in the hull top of the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, while aboard, No. 2 Canadian Tank Troops Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, devised a two-foot (one-metre) high shield, which fitted around the forward edge of the circular opening in the hull top. Major Bingham (the regiment’s second-in-command), inspected a ‘mock-up’ of this shield, which was fitted to one of the regiment’s ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, at No. 2 Canadian Tank Troops Workshop, on 27 October 1944. This proposed modification, however, was never adopted.

A mock-up of the proposed two-foot (one-metre) high shield, which fit around the forward edge of the circular opening in the Ram Kangaroo hull top, that was devised by No. 2 Canadian Tank Troops Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and was inspected by the regiment’s second-in-command, Major Bingham, on 27 October 1944, but was never adopted. MilArt photo archives

On 1 November, “A” Squadron was split into two squadrons, “A” Squadron, with Major Corbeau still commanding and “B” Squadron, under command of Major H. Baldwin10. By 2 November, all of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment was concentrated in Tilburg, along with both No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals. On 5 November, the overall strength of the regiment stood at 23 officers and 268 other ranks, holding a total of 85 ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers.

All of November was spent in Tilburg, organizing and getting the regiment ‘battle worthy’ for future operations, with maintenance being carried out on the carriers, which included the 100-hour check11 (an overhaul), since the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, was powered by a 450-horse power Continental R975/C1 radial air-cooled 9-cylinder engine, and on the incoming ones that dribbled in all month from Ordnance issues. Since the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, which 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron had been issued with back in October, had been converted and shipped to Normandy for issue, there had been no time for proper maintenance to have been carried out on them. Once landed in Normandy they were to have been ‘lifted’ by either rail or tank transporter to the point of issue to 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, but ended up being driven from the Normandy coast to Pierreval (France), and once issued to the squadron, were committed right into ‘active’ operations, so it wasn’t until the coming together of all of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in Tilburg, that the opportunity finally arose for full and proper maintenance to be carried out on these carriers. Captain Duncan’s, No. 123 Light Aid Detachment (Type E), Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, were aided by the British 821, and 826 Tank Troops Workshops12, Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, throughout the mouth of November, with both the 100-hour checks, and in doing minor repairs, on the regiment’s ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers. Captain Duncan, was also able to acquire much needed spare parts from both No. 2 Canadian Tank Troops Workshop, and No. 4 Canadian Armoured Troops Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers13.

CT160003, one of the initial 100 Ram, Mark II tanks, that were earmarked for conversion to that of a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier, on 10 August, and was shown as converted to a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier, by 26 September 1944, seen here in service with the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, in support of operations by the British 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division in the area of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Holland, on

22 October 1944. Authors’ collection

1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, was also kept busy throughout the month of November, in not only organizing themselves, but also in, insuring that all of the regiment’s communications equipment was in working order, and that all personnel of the regiment, who would be operating wireless sets (radios), knew the proper procedures, for there use. Eventually all of the regiment’s ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, was fitted with a No. 19 Wireless Set, with other designated carriers being fitted with a second No. 19 Wireless Set, or with No. 18, No. 22, or No. 38 Wireless Sets, as the need arose. In an effort to better improve the supply of spare parts and other essentials that the Signal Troop required, to keep the communications equipment of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in working order, on 4 February 1945, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, formally became a part of No. 4 Company, First Canadian Army Signals, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, although the remained attached to 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment.

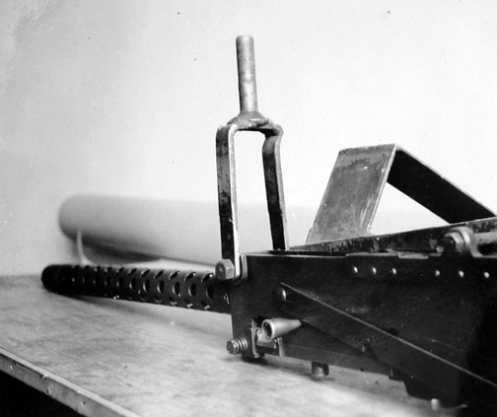

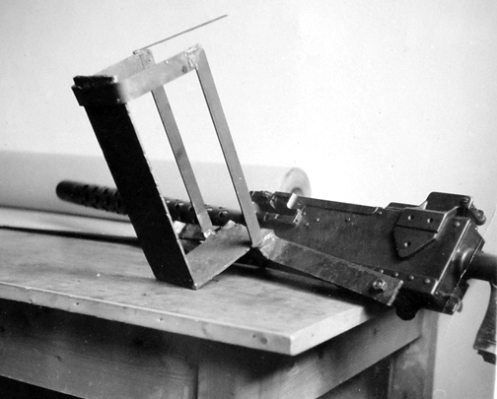

On 9 December 1944, the design for the secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun pintle mounting device and feed tray (which held one box of .30-calibre belted ammunition), that Captain’s Duncan, and Rook, had designed was approved by First Canadian Army Headquarters, with a pilot model being ready for inspection by both, on 14 December, at No. 1 Canadian Advanced Base Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, Brussels, Belgium. These mounts, were immediately ordered into production, by the Deputy Director of Mechanical Engineering, First Canadian Army14, with him directing that No. 1 Canadian Advanced Base Workshop, produce 130 of these mountings, so as a reasonable reserve could be held, to replace battle damaged ones. On 30 December, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, received 110 mounts, with the remainder to follow. Some of the regiment’s ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers, were eventually fitted with a third .30-calibre Browning machine gun, or with a single .50-calibre Browning heavy machine gun M2, in the turret ring. On 20 December, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, along with their attached Light Aid Detachment (No. 123), and Signal Troop, were placed under command of the British 79th Armoured Division15, with the regiment becoming part of the British 31st Tank Brigade16, which at the time, consisted of the British 141st Regiment (The Buffs), Royal Armoured Corps (equipped with Churchill Crocodile flame-throwing tanks), the British 1st Fife and Forfar Yeomanry (equipped with Churchill Crocodile flame-throwing tanks), and the British 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment (equipped with ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers). 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment (along with their attached Light Aid Detachment, and Signal Troop), were the only Canadian unit, to serve as part of the British 79th Armoured Division. It was also on 30 December, that the decision was taken, to hold in abeyance, the matter of the proposed expansion of 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, to four squadrons, as discussed at the conference which was held on 9 October 1944, at Headquarters 21st Army Group, to discuss the formation of armoured personnel carrier units.

An example of the simple .30-calibre Browning machine gun pintle mounting device, which Captains Duncan and Rook had designed. This fit into any of the bolt holes left by the removal of the turret ring during conversion to an armoured personnel carrier, enabling the mounting of a secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun. MilArt photo archives

An example of the feed tray, which held one box of .30-calibre belted ammunition, of the simple .30-calibre Browning machine gun pintle mounting device, which Captain’s Duncan, and Rook, had designed. MilArt photo archives

The secondary .30-calibre Browning machine gun pintle mounting device and feed tray (which held one box of .30-calibre belted ammunition), seen here mounted in the turret ring of CT159065, of “B” Squadron, 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, in Wertle, Germany, 11 April 1945. Authors’ collection

Although, as noted in “The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 1,” the basis of the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, was that they were based on the conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, other conversions of Ram, Mark II tanks, were also ‘converted’ to Ram armoured personnel carriers. On 2 November 1944, First Canadian Army decided that it no longer required any further ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers17, be produced to met its needs. Therefore, on 18 December 1944, Canadian Military Headquarters (London)18 instructed No. 1 Canadian Central Ordnance Depot, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps (Bordon Camp, Hampshire), that since there was no further requirement for ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, that the decision had been taken to convert all ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, currently held on stock by No. 1 Canadian Central Ordnance Depot, and those currently in the process of being converted to ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, at No. 1 Canadian Base Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, located at Bordon Camp, Hampshire, be converted to ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers. The initial conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of armoured gun towers, involved the removal of the complete turret, turret ring, and the internal ammunition bins, and the moving of the batteries up into the rear of the left-hull pannier, and the reinstallation of No. 19 Wireless Set, into the forward left-hull pannier. Stowage bins for 17-pounder ammunition, and a Tannoy loudspeaker system, were also installed, as was a towing hook on the rear, and one on the front hull. Therefore, their conversion to that of armoured personnel carriers, simply required the removal of the bins for 17-pounder ammunition, the Tannoy loudspeaker system, and the covering over of the drive shaft. The rear towing hook was to remain in place, while the front towing hook was to be removed, although this wasn’t always the case, as period photos show it still in place on some armoured personnel carriers. As a point of interest, during the initial conversion of Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, four hand grips (two on each side) were welded to the hull side to help the ‘gun detachment’19 in entering and existing the vehicle through the circular hole left in the hull top, by the removal of the turret. It is this author’s belief that these are the hand grips that are referred to in some contemporary accounts of the initial conversion of 100 Ram, Mark II tanks, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, by No. 1 Canadian Base Workshop (for First Canadian Army), in August-September 194420, as also, are the covering over of the drive shaft.

An example of the ‘Ram’ armoured gun tower, seen here towing the 17-pounder anti-tank, and ammunition limber. Note the two hand grips welded to the hull side, which helped the ‘gun detachment’ in entering and existing the vehicle. Authors’ collection

A rear view of a ‘Ram’ armoured gun tower, showing the rear towing hook which was retained as part of the conversion to that of a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier. Authors’ collection

A front view of a ‘Ram’ armoured gun tower, showing the front towing hook which was removed as part of the conversion to that of a ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carrier. MilArt photo archives

One draw back which was found from the conversion of ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, was that ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, had been originally converted from earlier model Ram tanks that had the auxiliary turret, on the left front of the tank. When converted to armoured gun towers, and the No. 19 Wireless Set, was reinstalled into the forward left-hull pannier, it was found the wireless set protruded into the co-drivers position, due to the contour of the hull, and would not fit snugly into the forward left-hull pannier. This protrusion of the wireless set into the co-drivers position, made the handling of the auxiliary turret mounted .30-calibre Browning machine gun practically impossible. However a few ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, converted to ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers, were issued to 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, before the problem with the repositioning of the No. 19 Wireless Set was discovered. With 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, having brought this problem to the attention of First Canadian Army Headquarters, they in turn, informed Canadian Military Headquarters (London), who in turn, advised No. 1 Canadian Base Workshop, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, the workshop responsible for conversions of ‘Ram’ armoured gun towers, to that of ‘Ram’ armoured personnel carriers. To remedy the problem, No. 1 Canadian Base Workshop, in December 1944, produced a simple kit for mounting the No. 19 Wireless Set over the transmission, between the co-driver’s, and driver’s position. These kits were made available to 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment Signal Troop, for the repositioning of the wireless set in those carriers which had been converted from armoured gun towers, to that of armoured personnel carriers. This modification, was also incorporated into the conversion of armoured gun towers, to that of armoured personnel carriers, by No. 1 Canadian Base Workshop.

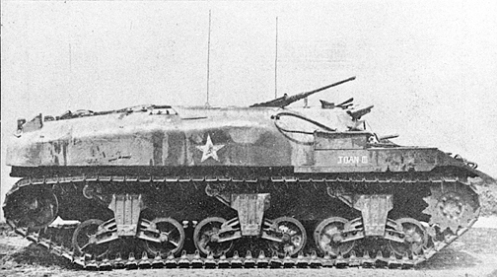

An example of a ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, with a single .50-calibre Browning heavy machine gun M2, mounted in the turret ring, as a secondary machine gun instead of a .30-calibre Browning machine gun. This particular vehicle, named JOAN III, was commanded by Captain (formerly Lieutenant) H. Kaiser, and was his third carrier, with his previous carriers, named after his wife, JOAN, and JOAN II, having become battle casualties. MilArt photo archives

To be continued in The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 3.

Notes:

- Lieutenant-General G.G. Simonds, normally the General Officer Commanding, II Canadian Corps, was appointed the Acting/General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, First Canadian Army, during the absence of Lieutenant-General H.D.G Crerar, General Officer Commanding -in-Chief, First Canadian Army, while he was away on sick leave in the United Kingdom, from 27 September to 9 November 1944.

- The Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, had been authorized on 28 August 1944, to support the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Canadian Armoured Corps.

- Formerly the Second-in-Command of the 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps.

- Formerly of the 6th Canadian Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars), Canadian Armoured Corps.

- The Deputy Commanding Officer.

- Formerly of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade Signals, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals.

- Formerly the Officer Commanding the Light Aid Detachment 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

- 14 Advanced Ordnance Depot, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, was located in the Rear Maintenance Area of 21st Army Group, which at this time was located around the French city of Bayeux, in Normandy, and contained all the static administrative and maintenance units, supporting the Second British Army, and the First Canadian Army, which were the two armies that made-up the 21st Army Group.

- The unit officer responsible for the maintenance, repair and recovery, of a unit’s equipment.

- Formerly of the 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps.

- The ‘Ram’ Kangaroo’s 450-horse power Continental R975/C1 radial air-cooled 9-cylinder engine, required a thorough check after every 100-hours of operation.

- From I British Corps, and XII British Corps, respectively.

- Both components of First Canadian Army Troops.

- The officer responsible for the maintenance and repair of First Canadian Army’s equipment.

- The British 79th Armoured Division operated specialized armoured vehicles modified for specialist roles.

- Which, on 2 February 1945, was redesignated the 31st Armoured Brigade.

- Also referred to as the ‘Ram’ 17-pounder Tower, had been developed in late 1943/early 1944, as a towing vehicle, to tow the 17-pounder anti-tank gun, which weighed 4,625-pounds (2,098-kilograms), and for the transportation of both the 17-pounder’s crew, ammunition, and associated equipment.

- Canadian Military Headquarters (located in London, England), held responsibility for coordinating the arrival, quartering, completing equipment requirements, and training of Canadian units and formations and to command and administer these units and formations in the United Kingdom and at base in the theatre of operations. In addition, the headquarters had an important liaison role, particularly liaison with the British War Office and with the General Officer Commanding Canadian Forces in the theatre of operations, as well as furnishing information to the Canadian High Commissioner in London.

- A ‘gun detachment,’ is the term used by the Royal Canadian Artillery for an artillery piece’s crew.

- See the ‘Ram’ Kangaroo armoured personnel carrier, Part 1, of 16 October 2014.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by James J. Boulton

These Canadian Army vehicle pennants were acquired in 1994 and identified at that time by the Director of Military Traditions and Heritage at National Defence Headquarters.

The triangular pennant was used by the rank and appointment of brigadier on the General Staff, typically employed at the Canadian Defence Liaison Staff in either Washington DC or London UK prior to unification of the Canadian Forces in 1968.

The rectangular pennant indicates the rank of lieutenant-general or above, at that time the Chief of the General Staff.

The rectangular pennant indicates the rank of lieutenant-general or above, at that time the Chief of the General Staff.