by Mark W. Tonner

Introduction

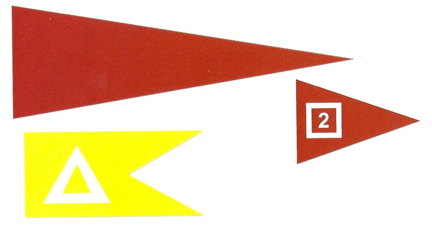

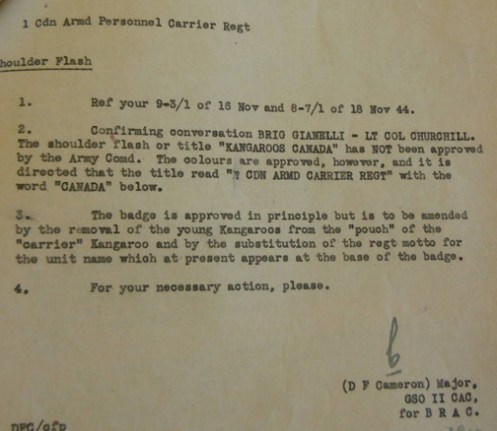

The Churchill Mark I was the first ‘Mark’ (the term (‘Mark’) used to designate different versions of equipment) of the Infantry Tank Mark IV, Churchill (A22). The Infantry Tank Mark IV, Churchill (A22) itself, was an ‘Infantry Tank,’ specifically designed for fighting in support of infantry operations. For this role, the requirements for an infantry tank, as the British General Staff saw it, were that the tanks have heavy armour, powerful armament, good obstacle-crossing performance, and reasonable range and speed. It was the fourth in the family of infantry tanks that had been developed by the British. The three previous infantry tanks developed by the British, was the Infantry Tank Mark I, Matilda I (A11), the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), and the Infantry Tank Mark III, Valentine. Within the Canadian Army Overseas, the units of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade were the main Canadian users of the Churchill infantry tank. Between July 1941 and May 1943, the brigade was equipped with the Churchill Mark I, Mark II, Mark III, and Mark IV tanks.

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment training on a beach near Seaford, Sussex, in July 1942. Source: MilArt photo archives.

The British development of the Churchill Mark I

The Churchill Mark I was designed by Vauxhall Motors Limited in Luton, Bedfordshire, England, who also acted as parent to a group of companies charged with the production of the Infantry Tank Mark IV, Churchill (A22). Working under tremendous pressure, Vauxhall Motors had the first tank completed and ready for testing in December 1940, only twenty-two weeks after having started detailed design work. Unfortunately, because they had been instructed to have it in production within one year, the possibility of detailed user and development trails was virtually eliminated. With the issue of the first production models of the Churchill to units to begin in June 1941, Vauxhall was forced to work straight from the drawing board. This lead to some “teething troubles” with a few futures in the design and construction of the tank in early models only, which could give rise to troubles not normally expected in service. Vauxhall addressed this issue by inserting a four-page small yellow leaflet (dated May 1941) into the Churchill tank user handbook, addressed to crews, mechanics and workshop personnel, listing the defects known in advance to all who would handle the vehicle, and to outline the precautionary measures necessary to minimize them, and to explain that the defects existed solely because of the inadequate time that was available for comprehensive testing. Despite the problems, it did not take long to correct all the Churchill’s defects, and for the tank to become mechanically a very reliable vehicle. Vauxhall’s engineering teams, seconded to British and Canadian regiments who were training with Churchill tanks, sent a steady stream of information back to the factory, which constantly led to modifications and improvements. The combination of the Vauxhall teams and the Churchill crews, working hand-in-hand through the first formative months of the Churchill’s service, led to their crews knowing their tanks more intimately than could have been achieved with the most intensive training. Coupled with the aforementioned measures, the decision was taken in November 1941, that a rework programme would be carried out to correct some of the tank’s more glaring faults, and to bring many Mark I and Mark II tanks up to the current standard of the Churchill Mark III. Vauxhall Motors in Luton, Bedfordshire, and Broom & Wade in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, England, were both authorized to turn their production lines over to this rework programme, starting respectively, on 1 March and 1 April 1942.

A description of the Churchill Mark I

The Churchill Mark I had 102-millimetre thick armour (with a minimum thickness of 16-millimetres), making it one of the most heavily protected tanks built to that time. It weighed approximately 39-tons, and was 7.4-metres in length, by 3.3-metres in width, and stood at a height of 3.8-metres. It was powered by a 350-brake horsepower, 12-cylinder, horizontally-opposed engine, which could produce a road speed of 25-kilometres per hour and a cross-country speed of 13-kilometres per hour. The Churchill Mark I had an onboard fuel capacity of 682-litres, carried in six interconnected fuel tanks, three each side, located within the engine compartment. Also, the Churchill Mark I had an auxiliary fuel tank mounted on the outside rear hull, which carried an additional 148-litres. This auxiliary tank was connected to the main fuel system, but could be jettisoned from the tank in an emergency. This gave the Churchill Mark I a total fuel capacity of 830-litres allowing a cruising range of 145 to 201-kilometres.

The Churchill Mark I mounted a 2-pounder gun (capable of penetrating 57-millimetres of armour at 457-metres) and a coaxial Besa 7.92-millimetre machine gun in the turret, along with a 51-millimetre smoke bomb thrower in the turret roof, and a 3-inch howitzer (with a range of 1,829 to 2,286-metres) mounted in the hull front plate alongside the driver. The armour piercing capability of the 2-pounder and the high explosive capability of the 3-inch howitzer gave the tank a balanced armament. The 2-pounder was considered to be obsolescent by 1940, but was still being produced in quantity to replace losses in France. The factories could not spare the time to retool for the production of a heavier gun, due to the urgent need to re-equip the British Army after Dunkirk. The 2-pounder gun had an elevation of minus 15-degrees to plus 20-degrees, while that of the 3-inch howitzer was minus five degrees to plus nine degrees. The traverse of the 3-inch howitzer mounted in the hull front plate was restricted by the width of the hull between the horns. The Churchill Mark I had a crew of five (a commander, a gun layer, a loader/(radio) operator, a driver, a co-driver/hull gunner) men, all of whom was cross-trained.

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment, note the placement of the 3-inch howitzer in the front hull plate. Source: MilArt photo archives.

A Churchill Mark I of the Three Rivers Regiment, note the restricted traverse of the hull mounted 3-inch howitzer. Source: MilArt photo archives.

The hull was divided into four compartments. At the front, the driving compartment also housed the howitzer gunner. Behind that was the fighting compartment containing the electrically-operated three-man (commander, gun layer, and the loader/(radio) operator) turret. Further to the rear was the engine compartment, followed by the rear compartment housing the gearbox, main and steering brakes, air compressor, auxiliary battery charging set, and a turret power traverse generator. The hull was constructed of flat steel plates connected together with heavy steel angle irons, with rivets being used to secure the plates to the angle irons. The floor was flat and free from projections, and panniers were provided at each side between the upper and lower runs of the track for storage of equipment. The construction of the panniers was described as a double box girder, because each pannier formed a rectangular structure on each side of the hull, which created a hull of immense strength. The whole hull structure was suitably braced by cross girders and by the bulkheads that separated the various compartments.

The large square door (escape hatch) provided in each pannier just behind the driver and hull gunner positions was an unusual provision for British armoured fighting vehicles of this period, but was also very welcome by crews. Many a crewman who served as a driver or hull gunner on a Churchill is alive today because of these pannier doors. These doors could be opened or closed only from the inside, but the locking handles were designed so that the doors were automatically secured when they were closed. Each of these doors was provided with a circular pistol port, and two pistol ports were also provided in the turret. Double-hinged doors were provided in the hull roof above the driver and front gunner. They were normally operated from inside, but could be opened or secured from the outside by using a suitable key.

The turret of the Churchill Mark I, which was cast entirely as one piece, was the first attempt by British steel makers to create a complete turret as a single bulletproof steel casting. Also, the turret of the Churchill Mark I, had no protective mantlet, instead having just three slots in the bulletproof steel casting for the 2-pounder gun, the coaxial Besa 7.92-millimetre machine gun, and the sighting telescope. The turret could be controlled electrically when the engine was running, or it could be rotated by hand when the engine was stopped. When controlled electrically, the turret could be rotated at a fast speed of 360-degrees in 15 seconds, or at slow speed in 24 seconds. A cupola that could be rotated by hand independently of the turret was mounted in the turret roof for the use of the tank commander, which was rotatable by hand independently of the turret. A large hatch, closed by steel doors, was provided for the loader and gunner. A No. 19 wireless set (radio) was housed in the turret. This set included an “A” set for general use, a “B” set for short range inter-tank work at troop level, and an intercommunication unit for the crew, so arranged that each member could establish contact with any one of the others.

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment, note the Mark I’s cast one-piece turret and the absence a mantlet. Source: MilArt photo archives.

For optics and viewing, the driver was provided with a large vision aperture, which could be reduced to a small port protected with very thick glass. When necessary the small port could also be closed. The driver and hull gunner both had periscopes, and there were two other periscopes mounted in the front of the turret for the loader and gunner. The commander’s cupola was fitted with two periscopes. A Churchill tank driver’s vision was more restricted than on other tanks, because the driving compartment was set back so far from the forward track horns. Churchill drivers could see ahead, but could see very little on either side of the vehicle, and they relied on the tank commander to warn them of obstacles.

The driver’s large vision aperture, which could be reduced to a small port protected with very thick glass. Source: MilArt photo archives.

As mentioned earlier, there was adequate provision for stowage of ammunition and equipment, with the Churchill Mark I, able to accommodate the stowage of 150 rounds of 2-pounder ammunition, 58 rounds of 3-inch howitzer ammunition, 4,725 rounds of 7.92-millimetre ammunition, and 25 smoke bombs. Additionally, each tank also carried one .303-inch Bren (Mark I) light machine gun with an anti-aircraft mounting and six 100-round drum type magazines, two .45 calibre Thompson sub-machine guns with six 50-round drum type and ten 20-round box type magazines each, and one Signal Pistol, No. 1, Mark III, with twelve cartridges (four red, four green, four white). Designated stowage locations for vehicle tools, spare parts, and equipment, and the crew’s personnel equipment, were also provided.

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment, note the Bren light machine gun in its anti-aircraft mounting on the turret roof. Source: MilArt photo archives.

The Churchill Mark I in Canadian service

On 4 December 1941, No. 1 Sub Depot of No. 1 Canadian Base Ordnance Depot, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, located at Bordon Camp, Hampshire, England, began to receive Churchill Mark I tanks from the British for issue to the three army tank battalions (later redesignated army tank regiments on 15 May 1942) of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade. The brigade (which was the first formation of the Canadian Armoured Corps sent overseas) had arrived in the United Kingdom at the end of June 1941, and was to have been equipped with the Canadian-built Infantry Tank Mark III, Valentine, before leaving Canada. However, because of delays in Canadian tank production, the British War Office was asked to lend tanks to the incoming 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade. These would be replaced with Canadian-built tanks when Canadian production problems were overcome. With the support of the British Army’s Commander of the Royal Armoured Corps, this endeavour was successful, and immediately upon arrival in the United Kingdom, 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade was able to draw equipment on a respectable training scale. The 11th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Ontario Regiment (Tank)) was equipped with the new Churchill Mark II tank (built to the same specifications as the Churchill Mark I, except that the 3-inch howitzer mounted in the hull front plate was replaced by a Besa 7.92-millimetre machine gun), straight from the Vauxhall Motors production line. In the meantime, until such time as more Churchill tanks became available, the Infantry Tank Mark II, Matilda II (A12), were issued to the 12th Canadian Army Tank Battalion (The Three Rivers Regiment (Tank)), and 14th Canadian Army Tank Battalions (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)), but by the end of December 1941, all three tank battalions of the brigade were equipped with Churchill tanks.

At this time, a Canadian army tank battalion was organized, equipped, and manned, as per the War Establishment of a Canadian Army Tank Battalion (Cdn III/1940/33A/1) of 11th February 1941. The war establishment was a document that specified the organization of a unit, and its authorized entitlement for personnel, vehicles, and weapons. The document was updated whenever the unit was reorganized or they received new equipment. Under War Establishment (Cdn III/1940/33A/1), a Canadian army tank battalion included a battalion headquarters, headquarters squadron, and three tank squadrons. The battalion headquarters included four cruiser or infantry close support tanks. The headquarters squadron had a squadron headquarters, an intercommunication troop with nine scout cars, and an administrative troop. Each of the three tank squadrons had a squadron headquarters and five tank troops, each with three infantry tanks. The squadron headquarters had three tanks: one cruiser or infantry tank, and two cruiser or infantry close support tanks. In all, each Canadian army tank battalion, was entitled to an overall tank strength of 58 tanks. Although initially issued to the army tank battalions of 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, against their war establishment entitlement of cruiser or infantry tanks, as time went on and more Churchill Mark II tanks became available (along with the Churchill Mark III in April 1942), the Churchill Mark I was employed in the squadron headquarters in place of the infantry close support tanks.

A reworked Churchill Mark I of the Ontario Regiment, note the driver’s small vision port protected with very thick glass. Source: MilArt photo archives.

Under the previously mentioned rework programme, Canadian-held Churchill Mark I tanks started to be withdrawn on 30 May 1942. These tanks were returned to the British Army’s Chilwell Mechanical Transport Sub-Depot, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, located at Vauxhall Motors in Luton, Bedfordshire, England. There, once all tank stores and wireless (radio) equipments were accounted for, the tank was struck off charge of the Canadian Army Overseas. New or reworked Churchill tanks were in turn issued to the Canadian Army Overseas through No. 1 Canadian Base Ordnance Depot, to replace those that had been turned in. From the end of May 1942 onwards, there was a continuous stream of Churchill Mark I tanks being withdrawn from the units of 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade and new or reworked Mark I tanks being issued to replace them. This process continued until March 1943, when the decision was made to replace the brigade’s Churchill tanks with the Canadian-built Cruiser Tank, Ram Mk II. Not all of the Churchill Mark I tanks operated by units of 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade had to be reworked. In July 1942, Canadian Military Headquarters (London, England) issued a list of tanks, that were not affected by the rework programme.

Two reworked Churchill Mark Is of the Three Rivers Regiment on exercise somewhere in England. Source: MilArt photo archives.

By the time of Operation Jubilee, the ill-fated combined operations raid carried out against the port of Dieppe, France, on 19 August 1942, the Calgary Regiment, held six Churchill Mark I tanks, all employed as close support tanks, with two each in squadron headquarters, of the regiments three squadrons. All six of these tanks were reworked Churchill Mark Is which had been recently issued (two on 20 June, and four on 6 July 1942) to replace Mark Is that had been withdrawn from the regiment under the rework programme. Of these six tanks, four were lost at Dieppe while serving with “B” and “C” squadron headquarters. The two Churchill Mark I tanks serving with “A” squadron headquarters returned to England, with the squadron not having landed. It would not be until 23 October 1942, that these losses to the Calgary Regiment would be replaced.

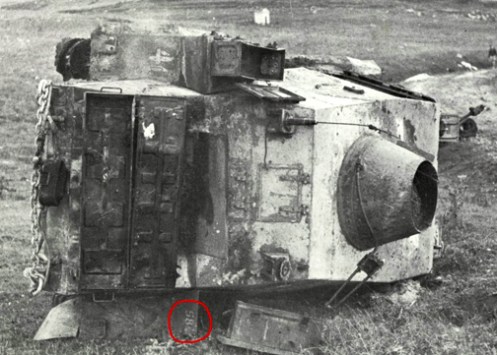

A reworked Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment’s “B” Squadron Headquarters knocked out at Dieppe. Source: Authors’ image file.

A reworked Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment’s “C” Squadron Headquarters knocked out at Dieppe. Source: Authors’ image file.

As of 5 January 1943, among the three tank regiments of 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, a total of 36 Churchill Mark I tanks (11 of which were reworked), were held on strength of the brigade. As of 1 March 1943, 16 reworked Churchill Mark Is, were held among the three tank regiments of the brigade. With the previously mentioned decision having been made to replace the brigade’s Churchill tanks with the Canadian-built Cruiser Tank, Ram Mk II, the brigade’s Churchill Mark I tanks, began to be withdrawn on 22 March 1943, with three Churchill Mark Is of the Calgary Regiment, being returned to No. 1 Canadian Base Ordnance Depot, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps (Bordon Camp, Hampshire). This was followed on 26 March, with the withdrawal of four Churchill Mark Is of the Ontario Regiment, and finally on 29 March, with the withdrawal of the six Churchill Mark I tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment, and the withdrawal of the remaining two from the Calgary Regiment. On 11 May 1943, the last remaining two Churchill Mark Is (which were held on strength of the Ontario Regiment), were turned over to the British 148th Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, at the British School of Infantry at Catterick, North Yorkshire, England. In all, at one time or another, between 4 December 1941 and 11 May 1943, approximately 70 Churchill Mark I tanks (24 of which were reworked Mark Is), were held on the strength of units of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade.

More information on the Churchill Mark Is which served with the Canadian Army Overseas can be found at Ram Tank under the Churchill Registry heading.

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to thank Clive M. Law, for providing photos from the MilArt photo archives, and for publishing this article.

Any errors or omissions, is entirely the fault of the author.

Bibliography:

Tonner, Mark W., The Churchill in Canadian Service (Canadian Weapons of War Series), 2010, Service Publications; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. ISBN 978-1-894581-67-7, and The Churchill Tank and the Canadian Armoured Corps, 2011, Service Publications; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. ISBN 978-1-894581-66-0.

- Canadian Militia List, published annually in Ottawa, years 1902 to 1914 ; Regulations for the Clothing of the Canadian Militia, Part II (Ottawa : Government Printing Office, 1909), pp. 37-38; for officer’s uniforms, see: David Ross and René Chartrand, ed., Canadian Militia Dress Regulations 1907 illustrated, with amendments to 1914 (St. John: The New Brunswick Museum, 1980). See the text of MUIA 852 for arms, accouterments and equipment.

- Regimental uniform notes taken in the Benson Freeman Collection, Army Museums Ogilby Trust, London, England (now closed) by the late Gen. Jack L. Summers in 1972, and transmitted to the author; “Short History of the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards”, The Salute, January 1936, pp. 11-14; William Y. Carman, “26th Canadian Horse (Stanstead Dragoons)”, The Bulletin of the Military Historical Society, August, 1985, pp. 26-28; 36th PEI Light Horse helmet in Worthington Museum, Canadian Forces Base Borden, Ontario; silken prints of Canadian uniforms done in 1913 for the Tuckett’s Tobacco Company of Hamilton, Ontario.

See the related article on Canadian Western Cavalry uniforms

by Mark W. Tonner

This brief article is a follow-up to my earlier article “Applications of unit serial numbers on vehicles of the Canadian Army Overseas, 1943-45,” of August 15, 2015.

During the period of the Second World War, as a Canadian unit was called out and placed on active service, it was allocated, a separate ‘Unit Serial Number.’ Each individual unit serial number, to all intents and purposes, became the unit identity code until such time as the unit was disbanded, although in some instances, a new unit serial number was sometimes allocated upon the conversion and redesignation of a unit. The unit serial number normally consisted of one, two, three or four digits. Early in the spring of 1943, with the pending involvement of formations and ancillary troops of the Canadian Army Overseas1, in the forthcoming invasion of the island of Sicily (in early July), Canadian Military Headquarters (located in London, England) in a series of mobilization orders, began the administrative process of preparing and organizing all units of the Canadian Army Overseas for operational duty outside of the United Kingdom. This process, basically ensured that all units were fully up to strength in terms of the number of personnel, types and number of vehicles, and equipment, each individual unit was authorized, as per their War Establishment and Equipment Tables. As units completed this mobilization process, a suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’ was added to each individual unit’s serial number, by Canadian Military Headquarters. The addition of this suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’ was twofold. Firstly it readily showed that a unit was ready for operational duty, and secondly, it differentiated between units of the Canadian Army Overseas and those of the British Army. This did not affect units of the Canadian Army (Active) serving within Canada, but upon transfer to the United Kingdom for service with the Canadian Army Overseas, the suffix of a backslash followed by the number ‘1’ was added to their unit serial number. This use of a backslash suffix followed by the number ‘1’ to a unit serial number as a means of identifying units of the Canadian Army Overseas, was purely administrative in nature, and after its inception came to be known as a unit’s ‘Mobilization Serial Number.’

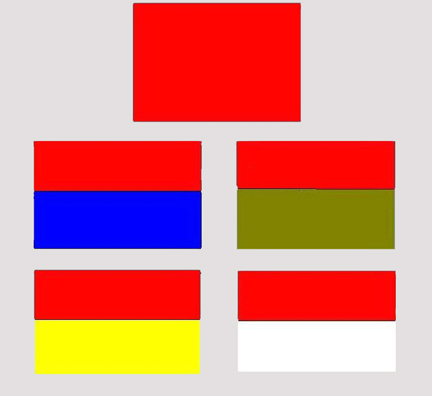

Although an elaborate scheme of Arm of Service, and formation markings was used on vehicles of the Canadian Army Overseas to ensure identification of units and efficient traffic control, starting with the Canadian Army involvement with the allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, the unit mobilization serial number (the unit serial number with the addition of the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’), was also used as a form of unit identification on vehicles, for the purpose of loading and shipping, as per the load tables for various types of vessels. In this form, they were sometimes referred to as an ‘Embarkation’ number, and were normally either chalked, stenciled, or painted free hand, in white on the front of a unit’s vehicles and were normally only carried on the vehicle for a brief period before embarkation, on the voyage, and for a brief period after landing. Besides being applied to unit vehicles, on their own, or as part of an embarkation number, unit mobilization serial numbers were also used to identify such things as unit kit bags, unit baggage, and unit stores. They were to be applied in white paint on dark coloured unit kit bags/baggage/stores, and in black paint on light coloured unit kit bags/baggage/stores, by use of a stencil, or free hand. In the case of unit kit bags, and other such baggage, an existing British War Office coloured bar code system was taken into use in the spring of 1943 (which was revised in May 1944), under which the last two digits of the unit serial number were represented by three horizontal coloured bars, which were normally painted on, directly below the application of the unit mobilization serial number, on a kit bag, or other such baggage, in which, the top and bottom bar represented the ‘tens’ digit and the middle bar represented the ‘ones’ digit. Purely as a point of interest, and although not part of the subject matter of this article, I’ve included as Table 1, a breakdown of the British War Office coloured bar code system that was taken into use in the spring of 1943, and of the revised May 1944 coloured bar code system.

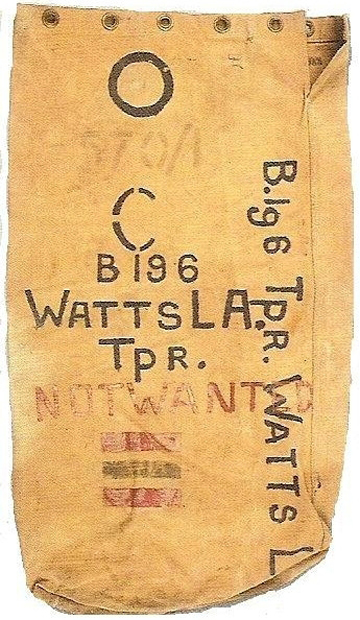

The following images are some examples of soldiers’ kit bags, and unit stores, onto which a unit mobilization serial number as been applied, as a form of unit identification. The first image is of a kit bag belonging to a Trooper L.A. Watts, which is marked with the unit mobilization serial number ‘570/1,’ which although rather faded, appears near the top opening of the bag, and identifies the kit bag owner as a member of the 1st Canadian Armoured Car Regiment (Royal Canadian Dragoons), Canadian Armoured Corps, whose unit mobilization serial number was ‘570/1.’ Note the application of the three horizontal bars of the coloured bar code system near the bottom of the bag. The second image is of a kit bag marked with the unit mobilization serial number ‘743/1,’ thus identifying the kit bag owner as a member of Le Regiment de la Chaudiere, whose unit mobilization serial number was ‘743/1.’ Again, the three horizontal bars of the coloured bar code system appear applied directly below the unit mobilization serial number, along with one vertical coloured bar, which was added by the regiment, too perhaps, identify the sub unit of the battalion to which the kit bag owner belonged (for the organization of an infantry battalion, please see the MilArt article “Basic Organization of the Canadian ‘Infantry (Rifle) Battalion’ on Overseas Service during the Second World War,” of 7 March 2014). In the last image, three soldiers of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada are having a meal in the area of Thaon, France, on 6 August 1944. Note the two stacked, dark coloured stowage boxes, to the left-rear of the standing soldier, both of which are marked with the Highland Light Infantry of Canada’s unit mobilization serial number of ‘754/1.’ Also note the application of the three horizontal bars of the coloured bar code system, which are applied directly below the unit mobilization serial number, on both stowage boxes.

The number ‘570/1’ identifies the kitbag owner as a member of the 1st Canadian Armoured Car Regiment (Royal Canadian Dragoons). Source: Authors’ image file

The number ‘743/1’ identifies the kitbag owner as a member of Le Regiment de la Chaudiere. Source: Courtesy of Ed Storey

The number ‘754/1’ identifies the stowage boxes as property of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada. Source: LAC/PA-213681

Unit serial numbers, on their own, were also applied to a soldier’s kit, as a means of identifying the soldier’s parent unit. In the image below, is an officer’s haversack which bears the unit serial number ‘944,’ and the corresponding three horizontal bars of the coloured bar code system. The unit serial number ‘944,’ identifies the owner of this haversack, as belonging to the 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps. The unit serial number ‘944,’ was initially allotted to The Elgin Regiment, Canadian Active Service Force, upon their embodiment as an ‘infantry’ battalion, in May 1940, and stayed as the Elgin Regiment’s assigned unit serial number, throughout the various conversions and redesignations, the unit underwent, until disbandment in February 1946. From their embodiment as an ‘infantry’ battalion, in May 1940, The Elgin Regiment was subsequently converted from an ‘infantry’ battalion, to that of an ‘armoured’ regiment, and was redesignated Serial No. 944, the 25th Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps, in January 1942. In September 1943, Serial No. 944, the 25th Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), was converted from an ‘armoured’ regiment, to that of a ‘tank delivery’ regiment, and was redesignated Serial No. 944, the 25th Canadian Tank Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps. This was followed in March 1944, by the conversion of Serial No. 944, the 25th Canadian Tank Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), from a ‘tank delivery’ regiment, to that of an ‘armoured delivery’ regiment, and redesignation to that of Serial No. 944, the 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps, which designation they kept until disbandment in February 1946.

An officer’s haversack which bears The Elgin Regiment’s unit serial number ‘944.’ Source: Courtesy of Michael Reintjes

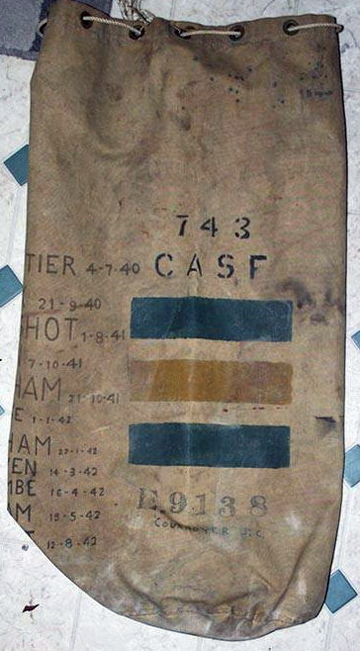

Another example of a unit serial number applied to a soldier’s kit, as a means of identifying his parent unit can be seen in the following image of a kit bag. In this case, the unit serial number ‘743’ of Le Regiment de la Chaudiere as been neatly stenciled onto the bag, with the corresponding three horizontal bars of the coloured bar code system (taken into use in the spring of 1943), applied directly below, thus identifying the kit bag owner as a member of Le Regiment de la Chaudiere. As a point of interest, Private J.C. Cournoyer, whose name and initials appear applied below his regimental number (E9138), near the bottom of the bag, transferred to the Royal 22e Regiment, and while serving in Italy was killed in action in December 1943. Also, the difference in the application of just the unit serial number ‘743,’ on Private Cournoyer’s kitbag, as opposed to the unit mobilization serial number ‘743/1,’ on the kit bag mentioned earlier, is that, Cournoyer’s bears the initial application from the spring of 1943. That of the earlier mentioned kit bag, with the application of the unit mobilization serial number ‘743/1,’ was applied sometime later, perhaps to the kit bag of a new member of the unit, as Le Regiment de la Chaudiere completed their preparations for the allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

The number ‘743’ identifies the kitbag owner as a member of Le Regiment de la Chaudiere. Source: Courtesy of Pascal Auger

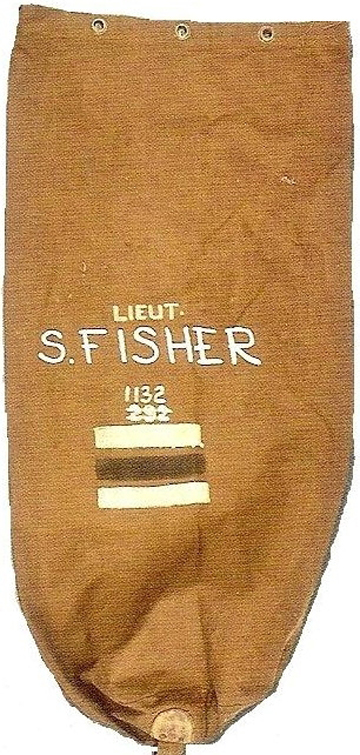

In the following image of a kit bag, belonging to a Lieutenant S. Fisher, the unit serial number of the unit he initially belonged to, No. 1 Canadian Artillery Reinforcement Unit, whose unit serial number was ‘292,’ as been crossed out, upon the Lieutenant moving onto a new unit. The new unit he moved to, No. 2 Canadian Artillery Reinforcement Unit, was allocated unit serial number ‘1132,’ which as been applied above the crossed out unit serial number of his former unit. The application of the three coloured bars of the coloured bar code system, corresponds to his new unit’s serial number of ‘1132.’ Also of note, is the absence of the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1,’ on either unit serial number. Both the Canadian Artillery Reinforcement Units to which Lieutenant S. Fisher belonged, were both static Canadian base units permanently stationed within the United Kingdom and were therefore, not subject to Canadian Military Headquarters’ mobilization process.

An officer’s kitbag, on which his old (‘292’) and new (‘1132’) unit serial numbers are applied. Source: Authors’ image file

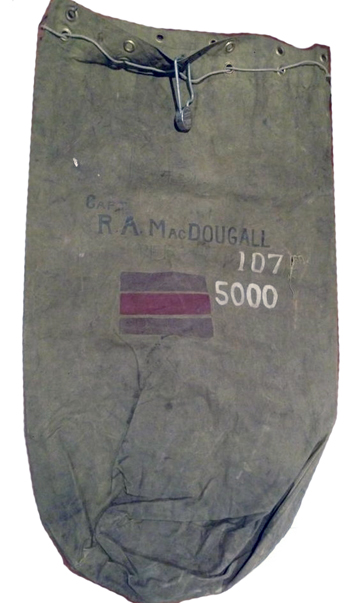

In the image below of a kit bag, marked as belonging to a Captain R.A. MacDougall, the unit serial number ‘107,’ in white, to the right of the three horizontal coloured bars of the coloured bar code system, identifies Captain MacDougall as a member of The Perth Regiment. Captain MacDougall was later promoted to the rank of Major, and was killed in action on 17 January 1944, while leading an attack in Italy. Major MacDougall was the highest ranking officer of The Perth Regiment killed in action during the Second World War.

The number ‘107,’ in white, identifies the kit bag owner as a member of The Perth Regiment. Source: Courtesy of Bill Donaldson

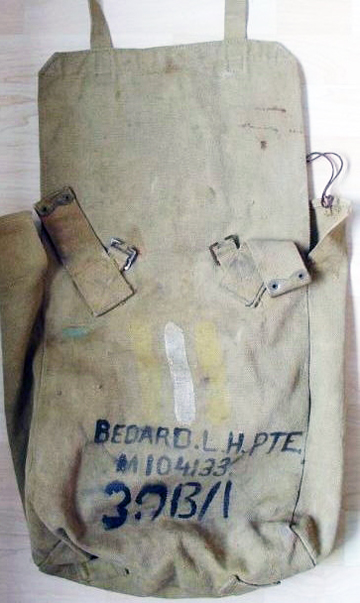

The large pack in the following image, belonging to a Private L.H. Bedard, is marked with the unit mobilization serial number of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), which was ‘39B/1.’ The 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry) was a component part of Serial No. 39, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division Support Battalion (The Saskatoon Light Infantry)2, whose corresponding coloured bar code can also be seen applied to the large pack, vertically, as opposed too horizontally, above the soldier’s name, initials, and regimental number. Although Serial No. 39B, the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry) was absorbed into the conversion and redesignation of Serial No. 39, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division Support Battalion (The Saskatoon Light Infantry) to that of Serial No. 39, The Saskatoon Light Infantry (Machine Gun) effective 1 July 1944, it would appear that the original unit mobilization serial number of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), of ‘39B/1,’ was retained on this particular large pack.

The number ‘39B/1’ identifies the large pack owner as a member of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry). Source: Authors’ image file

Table 1

a.) The British War Office coloured bar code system that was taken into use in the spring of 1943, under which numerals were represented by the following coloured bar:

- Red

- Blue

- Yellow

- Light Green

- Grey

- Buff

- Red Oxide

- Service colour (a deep bronze green)

- White

- Brown

b.) The revised British War Office coloured bar code system of May 1944, as promulgated in British War Office Publication 5697, entitled ‘Distinguishing Coloured Marks to be used on Stores Consigned in Bulk to Overseas theatres (British and US Forces),’ of 10 May 1944, under which numerals were represented by the following coloured bar:

- Red, bright, QD (Quick Drying)

- Blue, QD

- Yellow (Ammunition) (a bright yellow as used for ammunition markings)

- Green, light

- Grey (Ammunition) (a light grey as used for ammunition markings)

- Buff, QD

- Red, Oxide of Iron (a dark red similar to maroon)

- Deep Bronze Green

- White Lead, QD

- Brown, dark, QD

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to thank Clive M. Law, Ed Storey, and Michael Dorosh, for reading over my initial draft copy of this article, and their constructive criticism, and comments on it, and also, Miss Courtney Carrier, for proofreading, and corrections to my draft of this article, and also, Bill Donaldson, Ed Storey, Michael Reintjes, and Pascal Auger, for providing photos, and Clive M. Law, for publishing this article.

Any errors or omissions, is entirely the fault of the author.

Bibliography:

Law, CM, Unit Serials of the Canadian Army, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario.

Library and Archives Canada, archived photographs database, and digitized images, and various other Files/Volumes, Records Group 24, National Defence.

Tonner, MW, On Active Service, A summary listing of all units of the Canadian Army called out and placed on active service, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2008.

Notes:

- The Canadian Army Overseas, was the designation given, with effect from 30 December 1941, to that portion of the Canadian Army (Active), who were serving in the United Kingdom and would eventually serve in the Mediterranean (Sicily/Italy), and in the European theatres of operations.

- From the conversion and redesignation of Serial No. 39, The Saskatoon Light Infantry (Machine Gun) to that of Serial No. 39, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division Support Battalion (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), consisting of Serial No. 39A, Headquarters, 1st Canadian Infantry Division Support Battalion (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), Serial No. 39B, the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), Serial No. 39C, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), and Serial No. 39D, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), effective 1 May 1943.

Mark W. Tonner

With war in Europe inevitable, and as Canada prepared, starting on 1 September 1939, as a Canadian unit was called out and placed on active service, as a unit of the Canadian Active Service Force1, each unit was allocated, a separate ‘Unit Serial Number.’ Each individual unit serial number, to all intents and purposes, became the unit identity code until such time as the unit was disbanded, although in some instances, a new unit serial number was sometimes allocated upon the conversion and redesignation of a unit. The unit serial number normally consisted of one, two, three or four digits.

Some examples of the one, two, three, or four digit unit serial numbers allocated to Canadian units upon being called out and placed on active service:

a.) – Serial No. 2, was allocated to the Headquarters of the 1st Division (later redesignated Headquarters, 1st Canadian Division, and still later, was redesignated Headquarters, 1st Canadian Infantry Division) on 1 September 1939, and was retained as the unit serial number of the Headquarters until it was disbanded on 15 September 1945.

b.) – Serial No. 22, was allocated to the 2nd Field Park Company, Royal Canadian Engineers, on 1 September 1939, and was retained as the unit serial number of the 2nd Field Park Company until it was disbanded on 30 November 1945.

c.) – Serial No. 144, was allocated to No. 15 General Hospital, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, on 1 September 1939, and was retained as the unit serial number of No. 15 General Hospital until it was disbanded on 7 May 1945.

d.) – Serial No. 1177, was allocated to No. 6 Field Surgical Unit, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, on 1 February 1943, and was retained as the unit serial number of No. 6 Field Surgical Unit until it was disbanded on 1 June 1945.

In the case of units, such as a regiment of the Royal Canadian Artillery, that was made up of sub units that were each a component part of the parent unit, an alpha suffix letter was added to the one, two, three, or four digit unit serial number to identify each sub unit of the parent unit. As an example, Serial No. 10, was allocated to the 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, with the regiment’s sub units being allocated the following numeric/alpha unit serial numbers, Serial No. 10A, was allocated to Headquarters, 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, Serial No. 10B, was allocated to the 8th Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, Serial No. 10C, was allocated to the 10th (St. Catharines) Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, and Serial No. 10D, was allocated to the 7th (Montreal) Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery.

Early in the spring of 1943, with the pending involvement of formations and ancillary troops of the Canadian Army Overseas2, in the forthcoming invasion of the island of Sicily3, Canadian Military Headquarters in the United Kingdom4 in a series of mobilization orders, began the administrative process of preparing and organizing all units of the Canadian Army Overseas for operational duty outside of the United Kingdom5. As units completed this mobilization process, a suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’ was added to each individual unit’s serial number, by Canadian Military Headquarters. The addition of this suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’ was twofold. Firstly it readily showed that a unit was ready for operational duty, and secondly, it differentiated between units of the Canadian Army Overseas and those of the British Army. This did not affect units of the Canadian Army (Active) serving within Canada, but upon transfer to the United Kingdom for service with the Canadian Army Overseas, the suffix of a backslash followed by the number ‘1’ was added to their unit serial number. This also did not affect those units that were raised overseas under ‘Provisional War Establishments’ to cover experimental and temporary organizations and special courses of instruction under the authority of either Canadian Military Headquarters, or that of the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, these units continued to be identified by a number that was prefixed by the letters ‘CM’ (Canadian Military), ie: CM-xxx, which was assigned to them upon authority of their raising under either Canadian Military Headquarters or the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army6. Some of these temporary units/organizations were eventually called out and placed on active service under either an Order-in-Council7, or the authority of the Minister of National Defence, at which point they were authorized under a unit serial number, and in most cases, a new designation.

This use of a backslash suffix followed by the number ‘1’ to a unit serial number as a means of identifying units of the Canadian Army Overseas, was purely administrative in nature, and after its inception came to be known as a unit’s ‘Mobilization Serial Number,’ and was used in such things as Canadian Military Headquarters Administrative Orders and in Canadian Army Overseas Routine Orders. It also appears in use in Part II Orders issued by the Canadian Section, General Headquarters, 2nd Echelon8, in the United Kingdom, Sicily/Italy and North West Europe. As an example of the above mentioned, Serial No. 615, No. 1 Light Aid Detachment (Type A), Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps (which was attached to Headquarters, 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade of 1st Canadian Infantry Division), was mobilized as promulgated in Canadian Military Headquarters Mobilization Order No. 6 of 18 April 1943, under the supervision of Headquarters, 1st Canadian Infantry Division, with an effective date of 1 May 1943, at which time the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’ was added to their unit serial number, thus becoming, Serial No. 615/1, No. 1 Light Aid Detachment (Type A), Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps.

Another example would be the previously mentioned example of the 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, whose sub units, after having gone through this mobilization process, and the addition of the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1,’ would read Serial No. 10A/1 for Headquarters, 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, Serial No. 10B/1 for the 8th Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, Serial No. 10C/1 for 10th (St. Catharines) Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, and Serial No. 10D/1 for the 7th (Montreal) Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery.

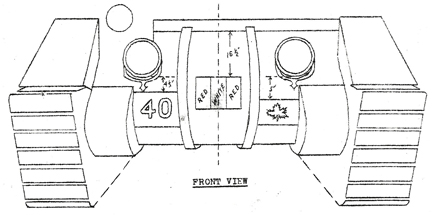

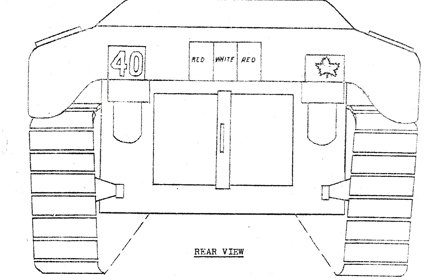

Although an elaborate scheme of unit and formation markings9 was used on vehicles of the Canadian Army Overseas to ensure identification of units and efficient traffic control, starting with the Canadian Army involvement with Operation HUSKY10 (the allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943), the unit mobilization serial number (the unit serial number with the addition of the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’), was also used as a form of unit identification on vehicles, for the purpose of loading and shipping, as per the load tables for various types of vessels. In this form, they were sometimes referred to as an ‘Embarkation’ number, and were normally either chalked, stenciled, or painted free hand, in white on the front of a unit’s vehicles and were normally only carried on the vehicle for a brief period before embarkation, on the voyage, and for a brief period after landing.

Examples of a unit’s mobilization serial number used as a form of ‘Embarkation’ number, for the allied invasion of Sicily, can be seen in the following three images, in the first of which (Image 1), the ‘32/1’ applied to the front edge of the fender of the two motorcycles, identifies these as belonging to the 48th Highlanders of Canada. In the next image (Image 2) although partially obscured by a length of chain, the ‘33/1’ applied on the left front fender, identifies this carrier as belonging to The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. In the third image (Image 3), the ‘10/1’ applied to the right-hand front of the storage box, on the carrier’s front, identifies this universal carrier as belonging to the 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery.

With the successful conclusion of the campaign on the island of Sicily, the Allies moved next against the Italian mainland, on 3 September 1943, with elements of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent)11, as part of Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey’s XIII British Corps, crossing the Straits of Messina from Messina, Sicily, to Reggio di Calabria, Italy, as part of Operation BAYTOWN12. As can be seen in the following images, the application of a unit mobilization serial number on unit vehicles was still very much in evidence into the first few months of the campaign on the Italian mainland. In the below image (Image 4) from October 1943, although only partially visible and oddly enough placed on the rear of the right-rear stowage bin, the stenciled application of ‘580/1’ (circled in red on the image) identifies this burnt out Otter, light reconnaissance car, as belonging to the 4th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment (4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards), Canadian Armoured Corps. In the next image (Image 5) from December 1943, the ‘37/1’ applied to the right-side of the bumper of this burning fifteen-hundredweight truck, identifies the vehicle as belonging to the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada.

By the time of Operation OVERLORD13 (the allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944), this use of a unit’s mobilization serial number (the unit serial number with the addition of the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1’), as an embarkation number, had involved a bit more, especially on unit vehicles of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent), and on unit vehicles of both Canadian Corps Troops, Canadian Army Troops, and ancillary units, that took part in the seaborne assault landings on 6 June 1944. Besides the unit mobilization serial number being used as an embarkation number, the ‘Landing Table Index Number (or Serial Number),’ which was the number specifically assigned to a vessel’s particular load, whether it was a load of vehicles, or personnel, or a mixture of both, and an abbreviation for the type of vessel in which the load was to travel, was now also added alongside the unit mobilization serial number.

As an example, Landing Craft Tank, pennant No. 1008, which was a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV, was assigned Landing Table Index Number (or Serial Number) ‘1715.’ Part of her assigned load were four Sherman Mark III tanks (with crews) of the 27th Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusilier Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps (of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent)), whose unit mobilization serial number was ‘1044/1.’ Each of these four individual Sherman Mark III tanks would have had the embarkation number ‘1044/1/1715/LCT(IV),’ applied to them, thus identifying each individual tank as belonging to the Sherbrooke Fusilier Regiment, which were assigned to load number ‘1715,’ which was assigned to a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV. Also assigned to the same Landing Craft Tank (pennant No. 1008), were two universal carriers (each with a four-man crew, with each carrier towing a 6-pounder anti-tank gun) of The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division), whose unit mobilization serial number, was that of ‘752/1.’ Each of these two universal carriers would have had the embarkation number ‘752/1/1715/LCT(IV),’ applied to them, thus identifying, each individual carrier, as belonging to the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, which were assigned to load number ‘1715,’ which was assigned to a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV. Another example, is for that of a 3-ton truck of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division), whose unit mobilization serial number, was ‘754/1,’ and was the only vehicle of this unit, assigned to the load carried by Landing Craft Tank, pennant No. 667, which was a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV, and was assigned Landing Table Index Number (or Serial Number) ‘1724.’ This solitary 3-ton truck of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, would have had the embarkation number ‘754/1/1724/LCT(IV),’ applied, identifying it as belonging to the Highland Light Infantry of Canada, assigned to load number ‘1724,’ which was assigned to a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV.

As an illustration of what was stated in the last two paragraphs, in the background of the image (Image 6) below is a Landing Craft Tank, pennant No. 610 (visible on the left-forward side of the vessel), which was a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV, and was assigned Landing Table Index Number (or Serial Number) ‘212’ (which is displayed in large white numbers, on a placid, and is affixed to the front of the vessel’s bridge). All four Sherman tanks seen in this image, belong to the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (of the 27th British Armoured Brigade (Independent)), whose unit serial number, was ‘1126.’ Although marked in a slightly different fashion, then that, which was explained in the above paragraph, they are all marked with the embarkation number ‘1126/LCT4/212,’ or ‘1126/LCT(IV)/212.’ The ‘1126,’ identifying each vehicle as belonging to the 13th/18th Royal Hussars, the ‘LCT4’ (or ‘LCT(IV)’), identifying the type of vessel that would carry them, as a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV, and the ‘212,’ identifying the load number (the Landing Table Index (or Serial) Number specifically assigned to the vessel’s particular load), that they were assigned to.

The following three images illustrate the application of the unit mobilization serial number, the landing table index number (or serial number), and the abbreviation for the type of vessel in which the vehicle was to travel, that was applied to Canadian vehicles taking part in the Normandy invasion of June 1944. In the first image (Image 7) of an M7 ‘Priest’ 105-millimetre self-propelled gun (named CARRIE), with the gun detachment preparing to take part in Operation OVERLORD, note the embarkation number ‘707/1/1524/LCT IV,’ that is applied across the bottom of the stowage rack on the front of the vehicle. This identifies the vehicle as belonging to the 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (‘707/1’), that was to be part of load number ‘1524’ (the Landing Table Index (or Serial) Number specifically assigned to the vessel’s particular load), which was to be carried on a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV (the ‘LCT IV,’ being the abbreviation for a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV). In the next image (Image 8) from July 1944 in France, note the application of ‘2351/1’ ‘FILM & PHOTO’ ‘T143MTS’ across the front bumper of a jeep. This identifies the vehicle as belonging to the 3rd Canadian Public Relations Group (‘2351/1’), while the stenciled ‘FILM & PHOTO’ on the centre portion identifies the task, or job of the jeep user, while the ‘T143MTS’ on the right identifies the jeep as having been carried to Normandy aboard Mechanized (or Mechanical) Transport Ship, pennant number ‘T.143.’ In the last image (Image 9) also from July 1944 in France, note the painted embarkation number, which reads ‘733/1 1712 LCT (IV)’ on the right of the lower portion of the jeep’s windscreen, which identifies the vehicle as belonging to the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (‘733/1’), that was part of load number ‘1712’ (the Landing Table Index (or Serial) Number specifically assigned to the vessel’s particular load), which was carried on a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV (the ‘LCT IV,’ being the abbreviation for a Landing Craft Tank, Mark IV).

As mentioned earlier, in the case of units, such as regiments of the Royal Canadian Artillery, that were made up of sub units, that was each a component part of the parent unit, an alpha suffix letter was added to the one, two, three, or four digit unit serial number, to identify each individual sub unit of the parent unit. Add to this the suffix of a backslash and the number ‘1,’ that was added to a unit’s serial number, as they completed the mobilization process, initiated by Canadian Military Headquarters, and, as an example, the 8th Field Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (of the 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery), whose unit serial number was ‘10B,’ would now have the mobilization serial number ‘10B/1.’ Examples of a battery’s unit mobilization serial number applied to their vehicles, as a form of identifying the vehicle’s user unit (aside form the standard ‘Arm of Service,’ and ‘Formation’ sign markings), can be seen in the following two images. In the first image (Image 10), note the application of the unit mobilization serial number ‘449/D-1’ on the extreme right side of the bumper, of a 3-ton, 40-millimetre self-propelled anti-aircraft gun, which identifies the vehicle as belonging to the 32nd (Kingston) Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, of the 4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, whose unit mobilization serial number was ‘449/1.’ In the second image (Image 11) of a T16 carrier towing a 6-pounder anti-tank gun, note the unit mobilization serial number ‘170D/1’ applied to the front edge of the right-hand fender, which identifies the vehicles as belonging to the 108th Anti-Tank Battery, of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, whose unit mobilization serial number was ‘170/1.’

In the following images are examples of a unit’s mobilization serial number applied to unit vehicles during First Canadian Army’s campaign in North-West Europe. In the first image (Image 12) from July 1944 in France, the mobilization serial number ‘1102/1’ applied in the upper left-hand corner on the front of the right-side fender of an armoured car identifies it as belonging to the 7th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars), Canadian Armoured Corps (the divisional reconnaissance regiment of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division). In the next image (Image 13) from October 1944 in Belgium, note the unit mobilization serial number ‘192/1’ applied to the front edge of the right-side fender of the universal carrier in the background. This unit mobilization serial number identifies the carrier as belonging to The Calgary Highlanders. In the last image (Image 14), which is taken rather late in the campaign in North-West Europe, showing Canadian vehicles passing through Uedem, Germany, on 2 March 1945, although the motorcycle and the three trucks on the roadway, all carry the same ‘Arm of Service’ marking of ‘67’ the 3-ton truck directly behind the motorcycle, also carries the unit mobilization serial number ‘187/1’ on the extreme right-side of its bumper, thus identifying these vehicles as belonging to Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal.

In a future article, the applications of unit serial numbers on kit/baggage/stores of the Canadian Army Overseas, 1943-45, will be looked at.

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to thank Clive M. Law, Ed Storey, and Michael Dorosh, for reading over my draft copy of this article, and their constructive criticism, and comments, on the draft, and also, Miss Courtney Carrier, for proofing reading, and corrections to my draft copy of this article, and Clive M. Law, for providing photos from the MilArt photo archives, and for publishing this article.

Any errors or omissions, is entirely the fault of the author, who unfortunately, cannot always remember everything.

Bibliography:

Law, CM, Unit Serials of the Canadian Army, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario.

Library and Archives Canada, archived photographs database, and digitized images, and various other Files/Volumes, Records Group 24, National Defence

MilArt photo archive, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario.

Tonner, MW, On Active Service, A summary listing of all units of the Canadian Army called out and placed on active service, Service Publications, Ottawa, Ontario, 2008.

Notes:

- The Canadian Active Service Force, was the designation given to those units of the Military Forces of Canada, that was called out and placed on active service, between the period of 3 September 1939, to 7 November 1940, upon which date, the Canadian Active Service Force, was redesignated the Canadian Army (Active).

- The Canadian Army Overseas, was the designation given, with effect from 30 December 1941, to that portion of the Canadian Army (Active), who were serving in the United Kingdom and would eventually serve in the Mediterranean (Sicily/Italy), and in European theatres of operations.

- The involvement of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, along with ancillary troops, in the forthcoming allied invasion of Sicily, as part of the Eighth British Army, was approved by Ottawa, on 27 April 1943, as communicated to the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, in the United Kingdom, by the Chief of the General Staff, Army Headquarters, Ottawa, in Telegram CGS 335, dated 27 April 1943.

- Canadian Military Headquarters (located in London, England), held responsibility for coordinating the arrival, quartering, completing equipment requirements, and training of Canadian units and formations and to command and administer these units and formations in the United Kingdom and at base in the theatre of operations. In addition, the headquarters had an important liaison role, particularly liaison with the British War Office and with the General Officer Commanding Canadian Forces in the theatre of operations, as well as furnishing information to the Canadian High Commissioner in London.

- This process, basically ensured that all units were fully up to strength in terms of the number of personnel, types and number of vehicles, and equipment, each individual unit was authorized, as per their War Establishment and Equipment Tables.

- As an example, the 1st Canadian Pile Driving Platoon, Royal Canadian Engineers, was embodied under unit serial number ‘CM 941,’ under the authority of Canadian Military Headquarters Administrative Order Number 20 of 1945, with effect from 1 February 1945. Serial No. CM 941, 1st Canadian Pile Driving Platoon, Royal Canadian Engineers, was disbanded under the authority of Canadian Military Headquarters Administrative Order Number 81 of 1945, effective 16 June 1945.

- A legal instrument made by the Governor in Council pursuant to a statutory authority or less frequently, the royal prerogative. All orders in council are made on the recommendation of the responsible Minister of the Crown and take legal effect only when signed by the Governor General.

- The Canadian Section General Headquarters, 2nd Echelon, was a Canadian Section that was attached to a “higher” headquarters’ 2nd Echelon (Example: to 2nd Echelon, 21 Army Group, in Northwest Europe, and to 2nd Echelon, Allied Forces Headquarters, in Italy), and whose primary responsibility was the provision of Canadian reinforcements for units in the field.

- Unit markings, also known as the ‘Arm of Service’ markings, were normally a 9½-inches by 8½-inches (24.1 by 21.6-centimetres) rectangle, consisting of a coloured background, appropriate to the formation, corps or branch of the service, to which the unit belonged, onto which a centrally located one, two, three, or four digit number, in white, was stenciled. These numbers, referred to as the ‘Arm of Service Serial,’ were blocks of numbers that were assigned to formations to identify individual units. Formation signs, which were normally a 6½-inches by 9-inches (16.5 by 22.9-centimetres) rectangle, were used to indicate the parent formation to which a vehicle’s unit belonged. The standardization, sizes, and positioning of all markings used on vehicles, followed the policy, as set down by either the Senior Officer, Canadian Military Headquarters, for formations under Canadian Military Headquarters control, or Staff Duties, Headquarters First Canadian Army, for formations under First Canadian Army control, which in turn, followed vehicle marking polices, as set down by the British War Office.

- Operation HUSKY, was the code name given to the allied invasion of Sicily, in which elements of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, and 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, took part in the seaborne assault landings on 10 July 1943, as part of General Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth British Army.

- The 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, had been redesignated the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent), with effect from 26 August 1943.

- Operation BAYTOWN, was the code name given to the Eighth British Army’s part, in the allied invasion of Italy, which commenced on 3 September 1943.

- Operation OVERLORD, was the code name given to the allied invasion of Normandy, in which elements of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade (Independent), took part in the seaborne assault landings on 6 June 1944, as part of Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey’s Second British Army.

by Clive Law

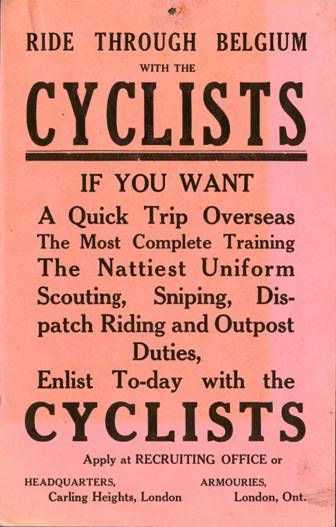

During the summer of 1959, the Queen, accompanied by Prince Philip, undertook the longest Royal tour in Canadian history (Buckingham Palace officials and the Canadian government opted to dub this a “Royal tour”, as opposed to a “Royal visit”, to dispel any notion that the Queen was a visiting foreigner.) The catalyst for the tour was the ceremonial opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, but beyond that, the intent was to visit many outlying districts never before visited by royalty. All ten provinces, four of the Great Lakes, both Territories (as existed at the time) and a visit to the United States were covered in an exhausting fifteen thousand mile, forty-five day tour.

In order to accomplish this task the Government of Canadian, with the logistical support of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps and the Royal Canadian Air Force, made plans for both road and air travel for the Royal guests. In the expectation of large crowds who would line the Queen’s route in every town and city it was decided that an appropriate limousine would be needed. The Government contacted each of the ‘big three’ car manufacturers and each offered to provide a limousine suitable for Royalty.

“For the Royal Tour of Canada in 1959, the Big Three auto manufacturers, General Motors. Ford and Chrysler, competed once more for the honour of transporting royalty, Her Majesty the Queen andPrince Philip. On lune 13, 1959 a Lincoln, a Chrysler, and a Cadillac — all to be used on the tour — were displayed before the Peace Tower at the Parliament Buildings. At first the government had considered using fourteen limousines and fourteen convertibles, stationing two in each of the cities to be visited. Then the decision was made to use only three and to fly them ahead of the royal couple. The Chrysler and Cadillac had removable glass tops over the rear passenger compartment and only the Lincoln was a convertible. “Her Majesty and Prince Philip will have every conceivable luxury… the flooring material looks like dyed mink. There is a button that enables the Queen to shift the seating arrangement in any one of six ways. The Ottawa wrote “Prince Philip gets to move his two ways, forwards and hack. The cars cost about $ 150,000 and look every dollar of it. The spare tires are covered in special cloth, which somebody recalled as mohair…. There is no armour plate or bulletproof glass, confided the Citizen reporter, “The royal couple have nothing to fear but too much affection from Canadians.” “Very handsome,” said Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who left a cabinet meeting to be photographed with the three cars. After the tour, the cars were auctioned off to the highest bidder.”[1]

These three cars were: A Continental Mark IV, a Cadillac Custom 1959 Fleetwood Limousine and a Chrysler-Ghia Crown Imperial (this was a 1957 model upgraded for 1959). The Cadillac and the Continental were customized with a Landau-style roof permitting the Queen and Prince Philip to not only be seen by her loyal subjects but also to allow them to stand. Individually powered rear seats are installed with controls for the horizontal and vertical movement located on the individual arm rests [in the right-hand armrest, the Queen’s side, was also located a knob for remote-control of the car’s radio]. The Cadillac seats were tailored in silver-grey McLaughlin Carriage cloth, with matching cushions, in a distinctive square biscuit and button design and the floor was carpeted with luxurious mouton which extended up the doors.

During the tour each of the three cars was air-lifted by an RCA C-119 Flying Boxcar requiring that each car be used on a rotation basis during the 6-week tour.

During the tour the three cars were ferried across the country by RCAF C-119 ‘Flying Boxcar’ aircraft.

The cars featured a maximum of comfort, convenience and luxury for the passengers with the greatest possible outside-inside visibility for the millions who lined the coast to coast parade routes. To provide an even greater measure of air-conditioned comfort, two additional outlets are installed in the rear compartment. The two new air-conditioned outlets are on the back of the front seat. In the Cadillac other special appointments included mouton-covered hassocks, a lap robe carrying a hand embroidered crest of the royal household [in hues of red and gold] and special lights to illuminate the Royal Couple during after-dark processions. Her Majesty certainly earned the right to some luxury as the 45-day visit included 17 military parades, 21 formal dinners, 64 guards of honour and 381 platform appearances.

A more complete description of the Cadillac states:

The upper portion of the car quarter panel has been removed from the rear door post on back. It has been replaced with a removable Plexiglas canopy that will permit onlookers the opportunity to view the royal procession even if the weather fails to co-operate. It is anticipated that in most parade points the car will operate with the top removed in the true landau concept. The roof is further modified with the addition of a 24-inch by 43-inch sliding panel. Electrically operated, the roof panel can be opened or closed from both the rear and front compartments.

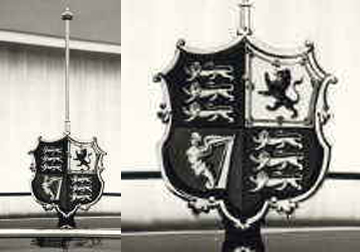

Each of the three cars had a Royal shield and had an anchored staff on the leading edge of the roof, centered above the windshield, for the royal standard. The Royal standard was fitted with a chrome rings that fit snugly into the staff.

One of the Royal standards used during the tour. The chrome stand with integral rings can be seen. Courtesy Dean Owen

Acknowledgement – Dean Owen for the loan of photographs as well as an original standard with staff.

[1] Royal Transport: An Inside Look at The History of British Royal Travel. Peter Pigott, Dundurn Press.

You can rate this article by clicking on the stars below

by Clive M. Law

The 48th Highlanders were authorized under General Order # of 1891 as the 48th Battalion (Highlanders) and took the spot vacated by the 48th Lennox and Addington Battalion when the latter were dissolved. As a highland regiment in the centre of Toronto the regiment attracted many of Toronto’s leading citizens and was, for many years, considered a wealthy regiment.

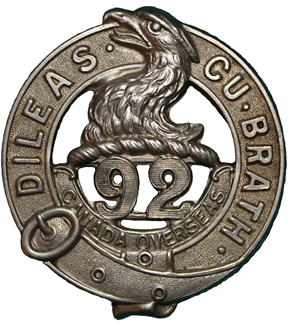

The 48th Highlanders chose a falcon over the number ‘48’ the whole encircled by a buckled belt upon which were the words ‘Dileas Gu Brath’ (Faithful Forever). The falcon’s head was taken from the family arms of the 48th’s first Commanding Officer, John Irvine Davidson. In approximately 1904 the badge was changed by adding a semi-circular banner below the falcon’s head upon which were the words ‘Highlanders’.

Original badge authorized for the 48th Battalion (Highlanders) (Black & white image). Courtesy Mark Passmore

It was with variants of this badge that the 48th went to war in 1914, having raised the 15th Battalion CEF as well as two reinforcement battalions, the 92nd and 134th Battalions CEF. All three battalions wore badges that immediately identified their link with the pre-war Militia Regiment.

Badge of the 15th Battalion, CEF. The link to the 48th Highlanders is unmistakable. Courtesy Mark Passmore

Badge of the 92nd Battalion, CEF. This battalion was broken up for reinforcements once in England. Courtesy Mark Passmore

Badge of the 134th Battalion, CEF. As with the 92nd Bn, the 134th was broken up and never saw active service in France. Courtesy Mark Passmore.

Following the First World War, the Commanding Officer of the 48th responded to a survey being undertaken by Militia and Defence Headquarters (later National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ)) by supplying a card with all of the regiment’s badges. The purpose of this 1921 survey was to update the badge descriptions in Dress Regulations, the last comprehensive set of these dating to 1907. In the 1907 Dress Regulations the badge was described as:

A falcon’s head (compel), or, resting on a bar, beneath which is placed the numerals “48”, in Roman block, all surrounded with a circular ribbon bearing the motto Dileas Gu Brath. Silver for officers, white metal for N.C.O.s and men.

Badge adopted in 1904 but not recorded in the 1907 Dress Regulations. It was this badge that the Regiment wished to maintain after the First World War and through the argument over the ‘Garter’ belt. Courtesy Mark Passmore

NDHQ approved the design that had been taken into use in the intervening years and published General Order 71 of 1922 which now described the badge as:

Gilt. Within a circular riband inscribed “Dileas Gu Brath” the numerals “48” above which, on a bar, is a falcon’s head: Below the numerals is a semi-circular scroll, inscribed “Highlanders”.

It is surprising that NDHQ approved this design as it was contrary to Militia Order 208 of 1906 which had already raised the issue of the improper use of the Garter and which was quoted in the March 1929 letter.

Regrettably, a number of documents are missing from the archival files but it is known that in May 1929 the Adjutant of the 48th Highlanders wrote to NDHQ (via the Military District No.2 Adjutant) that a drawing showing their badge was incorrect. The author infers that the drawing provided by NDHQ was instigated by a policy change for badges in the Canadian Militia that required all badges featuring the Belt of the Order of the Garter to be replaced. By policy, any buckled belt was seen as an infringement of this ‘honourable and ancient’ design. The use, or permission to use, was solely a Royal prerogative.

The policy saw a number of Militia regiments forced to change their badges; however, the cost of such change was to be borne by NDHQ and not on the individual regiments. It was immediately obvious that the 48th Highlanders were not pleased with the proposed change and the Adjutant drafted a letter, on 6 May 1929, complaining about the drawing, stating:

The attached drawing is not concurred in by this Regiment. […] The design submitted [by NDHQ] is not a garter but just a circle. There is no buckle nor strap; also the scroll under the falcon is not properly finished but disappears in an uncertain way underneath the circle. The falcon head also seems to lack a spirited, erect carriage…

The 48th Highlanders Adjutant referred to his letter’s letterhead which, according to the Adjutant, was the badge which the regiment wished to continue wearing. NDHQ replied that the regiment’s design ‘is incorrect’ and referred the Adjutant to Circular Letter No. 7, dated 5 March, 1929 (the original letter stating that it was ‘incorrect and improper for the ‘Garter’ to bear any inscription other than the motto of that Order.)

Little more was said until the 21 September, 1929 when Lt-Col Sinclair, DSO MC, Chairman of the Regimental Dress Committee forwarded a report to NDHQ. Copies of the report have not been located but it was not well-received at NDHQ. However, a copy of Headquarters’ reply survives. No less than the Adjutant-General himself, Major-General Panet, wrote “…the nature of the remarks […] constitutes a serious breach of discipline.”

Panet’s letter caused Lt-Col Sinclair to immediately apologise and explain that the report had not been endorsed by Lt-Col H.M. MacLaren, Commanding Officer of the 48th Highlanders and he regretted any idea of discourtesy. Lt-Col MacLaren also wrote to the District Officer Commanding, to be forwarded to NDHQ, asking that the report be returned in order that the regiment could submit a new report.

A few days later the MacLaren wrote:

This Regiment had no idea that our Badge infringed in any way on the Badge of the Garter and had no desire or intention of doing so. It was authorised officially when the Regiment was formed, has been used ever since and was worn with honour by our service battalion in France. In this way it is carved on many graves in France and Belgium and the regimental monument in Toronto, as well as on our cups, plate and equipment.

The suggested badge does not meet with the approval of the officers of the Regiment and it is with the greatest reluctance that we bring ourselves to consider any change. As this is a matter that affects all officers, both past and present, we would like to bring it to their attention, which we intend to do shortly, when a further report will be forwarded.

NDHQ was satisfied that the 48th Highlanders would now give due consideration to their future badge and agreed to a delay. However, on 10 December 1929, the 48th Highlanders submitted new arguments for the retention of their existing badge:

On carefully examining the Badge of the Order of the Garter and comparing it with the Regimental Badge, a number of differences are noted.

The Regimental Badge should be more correctly described as a Buckle, and not a Garter, as the Garter has a completes circle for its clasp, whereas the buckle of ours has only a single piece for the clasp. Moreover, the loose end of the Garter in its dependent part finishes as a tassel, as in garters, known in Highland dress as a garter knot, whereas ours has no such tassel. Further, the circle in our Badge is broken in the upper part with the Falcon’s head erased which is superimposed upon it and projects over the upper edge.

The Garter being of such antiquity that, we are sure, nothing would be allowed to be placed over it, thus upsetting its continuity.

The motto in the circle of our Buckle is a Gaellic (sic) one, fitting for a Highland Regiment.

We would therefore respectfully suggest that for these reasons our Crest is in no way an infringement on the Ancient and Honourable Order of the Garter, and that permission be granted to us to continue in the use of our present badge which has been in use for years and is engraved on our monument, silver, etc.

Headquarters was not swayed by the argument and replied that the ‘actual shape or design of the buckle used’ was immaterial and that there was ‘no doubt that the buckled band…is incorrect’. NDHQ re-iterated that, while present stocks could be used up, future supply was to conform to the amended design.

In mid-January 1930, NDHQ followed up with the 48th Highlanders who requested that as a change in the regimental title (from 48th Regiment (Highlanders) to the 48th Highlanders of Canada) was the subject of a meeting with the officers of the regiment, that their reply be held in abeyance. NDHQ agreed to the delay.

On 20 March 1930, NDHQ was asked to approve the name change but, before NDHQ agreed to this, they raised the question of badges – again. On 12 July NDHQ wrote:

National Defence Headquarters advises that before further action is taken to approve the change in title of the 48th Regiment (Highlanders) the question of the cost of new badges is to be brought to attention.

As stated in previous correspondence the cap badge of the Regiment requires modification, viz, the Garter has to be replaced by a double circle.

The cost to the Department of this alteration would be approximately $50.00

Should you desire to have new designs of badges as the result of the proposed change in designation, the cost at new dies and tools and a complete issue of badges must be borne regimentally.

In order to move forward with the new regimental designation they reluctantly agreed to the change in badge design and, consequently, General Order 99 of 1930 authorized the change. Within days NDHQ asked the 48th Highlanders what action they had taken to ‘with a view to correcting the badge’ and that, if no action had yet been taken, at what date ‘that such will be done’. The regiment replied that ‘the unit is not at the present time in a financial position to undertake the expenditure involved in furnishing dies, tools and new badges’ and that the matter be ‘left in abeyance for the time being’. This reply was to set the tone for several years to follow.

In June 1931, NDHQ asked again. The regiment again stated that they could not afford to make the change-over.

In October 1932, NDHQ asked again. The regiment pleaded poverty again.

In March 1933, NDHQ asked again. The regiment repeated their inability to pay at that time.

In April 1934, NDHQ asked again. The regiment asked for the matter to be held over, again.

In October 1934, NDHQ asked again. The regiment asked for yet another extension.

In October 1935, NDHQ asked again. The regiment repeated their request for yet another extension.

Finally, in October 1936, NDHQ draws a line in the sand and sets distinct expectations from the 48th Highlanders:

With reference to your letter of the 25th October and previous correspondence on the marginally noted subject, I am directed to forward to you the following information on this matter.

The design of the “ground” upon which the motto “DILEAS GU BRATH” is placed comes within the scope of what is deemed to be a “garter”. As the Garter motto only, is permitted by His Majesty to appear on the “garter” in any crest or badge, it is regretted that the continuance of the “garter” design on the badges worn by the unit under your command must cease.